Travel without Limits

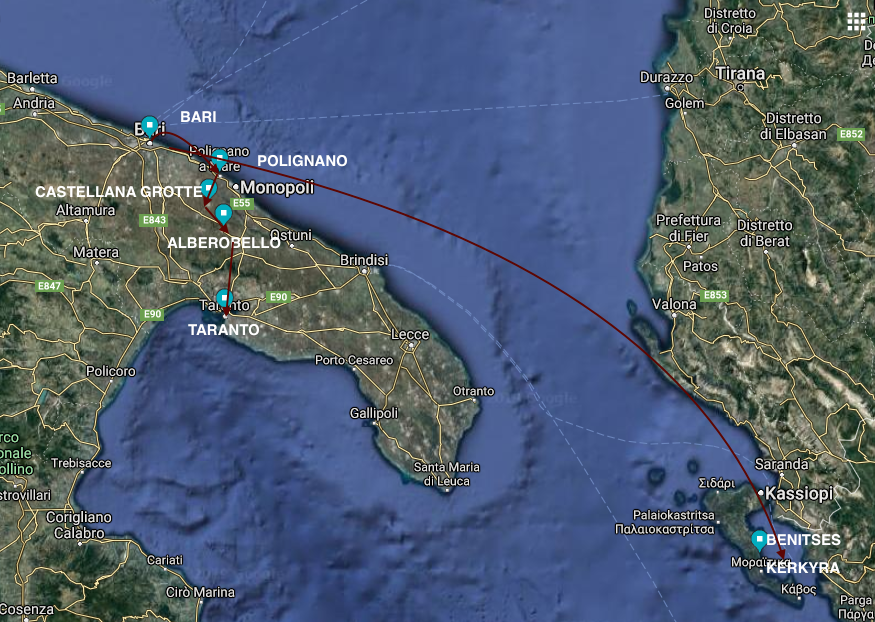

Bari, Polignano, Castellana Grotte, Alberobello, Taranto, Corfù, Benitses

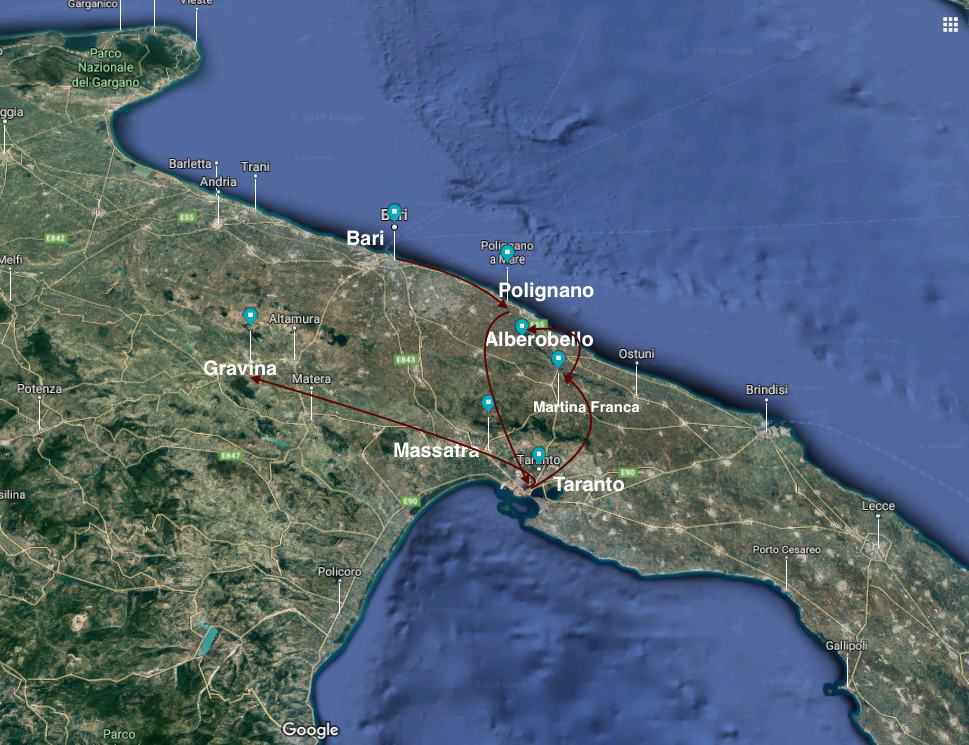

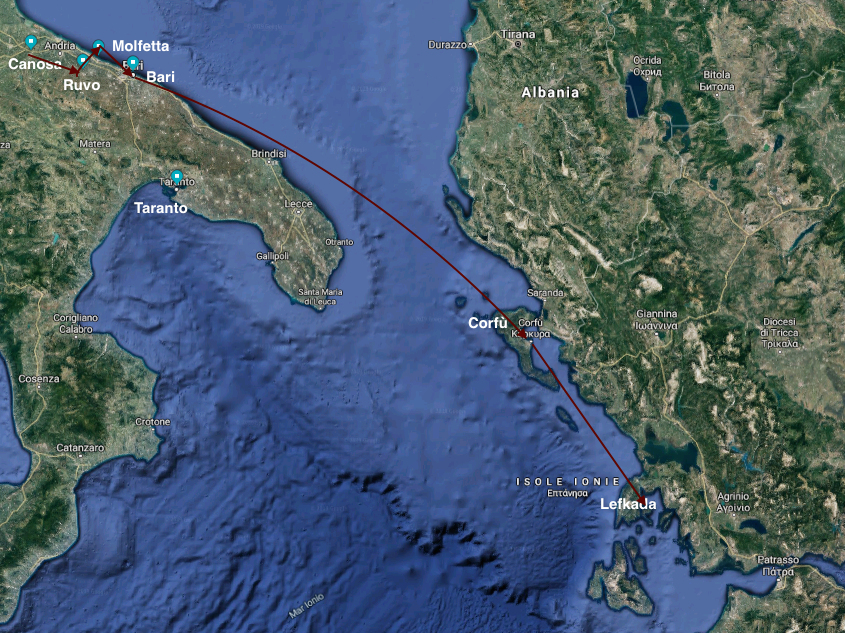

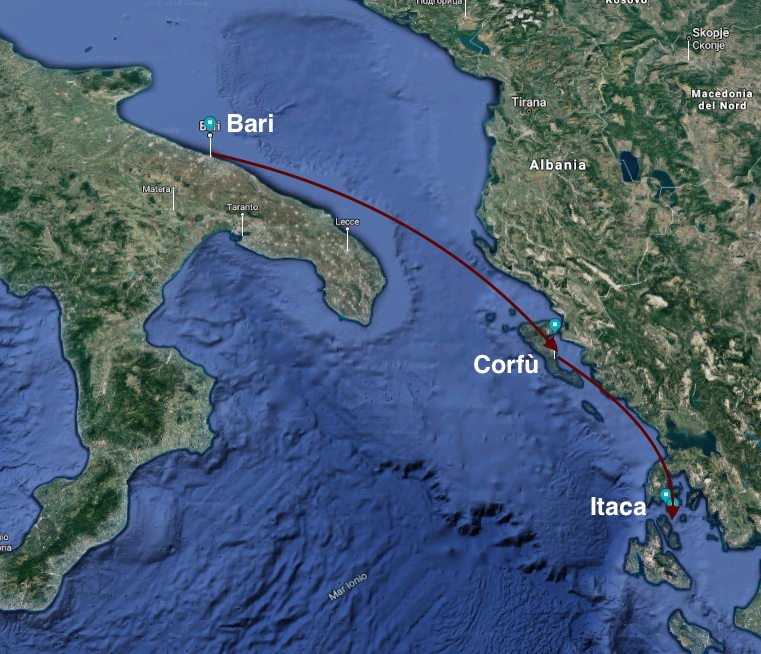

This itinerary was conceived to satisfy the legitimate desire to travel and to get to know each other. In order for the travel to be an inclusive and stimulating experience and for us to enjoy its magic to the full, we have designed a path that is as free from architectural barriers, but rich in cultural stimuli and scenic beauty. This is not a “different” itinerary, but an itinerary for everyone, without any limits, as the title suggests. Bearing this in mind, we have decided to include in the tour that we propose shere ome of the destinations of all the itineraries already conceived within the Polysemi portal, which meet as much as possible the necessary requirements for travelers with special needs; these itineraries are told by intellectuals who traveled before us between Puglia and the Ionian Islands. During the construction of this itinerary we realized how various projects have recently been carried out to adapt architectural, landscape and cultural heritage in terms of accessibility for some types of needs; however, there is still much work to be done to ensure real usability for all travelers. In our “limitless” itinerary, places without barriers that hinder mobility and practicability have been included; for each destination, any aids that guarantee the usability of the place for different types of needs have also been indicated. We have created mini itineraries summarized through visualized maps, which facilitate their consultation.

ACCESSIBILITY: barrier-free route (flat, with ramp, elevator), tactile route from the station entrance to the tracks

USABILITY: sound and visual information systems available to the public

(Courtesy of Di Haragayato – Photo taken by Haragayato using a FinePix40i, and edited., CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=909819)

The first stop on our itinerary is Bari. Whether you arrive by plane or reach the city by train, the journey can begin safely, since both the airport and the central railway station are accessible. In particular, further restructuring works are currently underway at Bari Central Station which will guarantee improved usability. We would like to point out that the “light path” starts right from the station, with a route designed for the blind and visually impaired that runs for about 2.5 km in the Murat center of Bari. It is one of the longest tracks in the world and is made of tactile bricks that indicate free routes, relative detours, road crossings and obstacles that can be overcome; however, it should be noted that the traffic lights are not equipped with acoustic signals, so we recommend accompanying blind people. Pier Paolo Pasolini arrived in Bari in 1951, and the great poet and filmmaker will accompany us in our descovery of the Muratian village of the Apulian capital, the city to which he dedicated the story Le due Bari. Arriving in the evening in an unknown city is a adventure for every traveler and for Pasolini the arrival in Bari takes on the features of an adventure with Kafkaesque outlines.

This is what he writes:

Kafka, ci vuole Kafka. Scendere dal rapido, non potere entrare in città né avanzare di un passo fuori dal viale della stazione, può accadere solo al personaggio di un’avventura kafkiana […], io ero rimasto solo, a tremare, nel piazzale rosso, verde, giallo della stazione: in me lottavano ancora la seduzione dell’avventura e un ultimo residuo di prudenza. (P. P. Pasolini, Le due Bari)

The feeling of bewilderment felt by the poet must not frighten us: it is the same feeling that each of us could experience once arrived at the central station of the Apulian capital and we see an orthogonal checkerboard grid of streets open in front of us, which can all seem the same and are the result of a 19th century urban restyling project promoted by Gioacchino Murat. The new Bari, developed outside its old medieval walls according to the nineteenth-century aesthetic canons of modern European cities, is an orderly succession of streets and avenues that draw a geometric pattern which is totally foreign and almost juxtaposed with the disordered Mediterranean texture of the alleys that characterize the old Town.

It is better not to take a random road, as Pasolini did: «così senza aver deciso nulla, scelsi una strada, una delle tante, piena di scritte luminose e mi incamminai», we recommend instead to continue along via Sparano, the wide pedestrian shopping street in Bari. Here you can admire Palazzo Mincuzzi, one of the most beautiful and extravagant Art Nouveau buildings in Bari.

At the end of Via Sparano the traveler can continue along Corso Vittorio Emanuele; from here we have outlined three possible paths:

Itinerary

1

At the end of Via Sparano, turning right and taking Corso Vittorio Emanuele, the Teatro Margherita stands out scenographically in its elegant liberty forms; today it represents the Polo of contemporary arts, a prestigious venue for exhibitions and international art exhibitions, equipped with accesses and accessible routes.

As soon as you pass the Margherita theater, a short distance from Piazza IV Novembre, the ancient port basin of Bari opens; in dialect it is called ‘nderre alle lanze’, that is to say land on the spears, with reference to the landing of small and typical boats of fishermen who, even today, are not too different from those who enchanted Pasolini. Here the traveler will be able to watch, as happened to the poet, the colorful secular ritual that takes place every morning: the sale of fish on often improvised stalls, the tastings of octopuses and raw molluscs taken by tourists and citizens.

From the Teatro Margherita going south, you can go towards the sea, which is a constant presence of Pasolini’s Bari and reveals itself in its Adriatic splendor especially in the morning.

As Pasolini writes:

Alzato il sipario del buio, la città compare in tutta la sua felicità adriatica.

Senti il mare, il mare, in fondo agli incroci perpendicolari delle strade di questa Torino adolescente: un mare generoso, un dono, non sai se di bellezza o di ricchezza. Davanti al lungomare (splendido), sotto l’orizzonte purissimo, una folla di piccole barche piene di ragazzi (i ragazzi baresi alti e biondi, coi calzoni ostinatamente corti sulla coscia rotonda, la pelle intensa, solidi) si lascia dondolare nel tepore della maretta. Nella luce stupita si incrociano i gridi dei giovani pescatori: e senti che sono gridi di soddisfazione, che il mare dietro la rotonda è colmo di pesciolini trepidi e dorati. E mentre il mare fruscia e ribolle, senti dietro di te con che gioia la città riprende a vivere la nuova mattina! (P. P. Pasolini, Le due Bari)

We therefore recommend walking along the wide sidewalk of the city promenade in the morning, when the colors of the sky and the sea are reflected in each other. The sea is always next to the traveler, flanked by a rhythmic succession of cast iron lampposts that allows you to glimpse the shapes of the city with its perfectly recognizable silhouettes, from the bell tower of the Cathedral to the monumental fascist buildings. Continuing our walk in a southerly direction, the city seems to undergo a metamorphosis, the elegant Liberty-style buildings and the bright colors of the marina give way to the ostentatious monumentality of Fascist architecture which in the 1920s and 1930s redesigned this stretch of the Bari coast.

Continuing along the seafront, we recommend a visit to the Corrado Giaquinto Provincial Art Gallery which is located on the top floor of the former Palazzo della Provincia, now home to the Metropolitan City of Bari. The building has an accessible lift; however, there are no aids for the visually impaired or blind, in addition to the audio guides. The building is one of the most representative of the Bari architecture in the fascist period, characterized by the eclectic recovery, in a monumental key, of elements of the Italian and ancient Roman civic Renaissance tradition. An interesting route of southern art runs from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century along the sixteen rooms of the city museum.

Continuing the walk along the Lungomare, for those who wish it is possible to reach the town beach of Pane e Pomodoro which, thanks to the No Barrier project financed by the Interreg Italy-Greece 2007-2013 program, has been equipped with the infrastructure and aids necessary to improve its usability (for example by people with reduced mobility or elderly people).

Itinerary

2

At the end of Via Sparano, turning right and taking Corso Vittorio Emanuele, at the intersection with via Cavour, we find, on the left, Piazza Ferrarese, the true antechamber of the historical center. Here, on Easter 1957, the writer from Piedmont Lalla Romano also arrived on a journey that would take her to Greece. This “long, wide, calm” square evokes family memories.

The square, which is today one of the night spots of nightlife in Bari, owes its name to a merchant from Ferrara who lived and made his fortune in Bari in the seventeenth century. It is still possible to observe the pavement of the Roman Via Appia-Traiana which used to pass through Bari precisely in this point of the city. On the left is the Murat room, an environment that hosts contemporary art exhibitions and, a little further away, you can see the apse area of a small church, called La Vallisa, dating back to the eleventh century. This place, which is now used as a diocesan auditorium, was the church of the community of Ravellese and Amalfi merchants in the Middle Ages.

On the right of the square is the building which was once the ancient municipal fish market. Piazza Ferrarese has always represented the elegant entrance to the old city which, through narrow streets, alleys and wide, introduces the traveler to its centre which holds many surprises. Traveling through the alleys of the city, the traveler cannot help but notice how Bari Vecchia seems to shine with its own particular light, in spite of the narrow and shady alleys.

Pasolini wrote:

Qui tutto è chiaro: anche la città vecchia, dalla chiesa di San Nicola al castello svevo pare perennemente pulita e purificata, se non sempre dall’acqua, dalla luce stupenda. (P. P. Pasolini, Le due Bari)

In the light of Bari, in 1964 Pasolini will dedicate intense verses whose reading could make the continuation of our itinerary more poetic and would let us discover the jewels of the old city.

Un biancore di calce viva, alto,

– imbiancamento dopo una pestilenza

– che vuol dir quindi salute, e gioiosi

mattini, formicolanti meriggi – è il sole

che mette pasta di luce sulla pasta dell’ombra viva, alonando, in fili

di bianchezza suprema, o coprendo

di bianco ardente il bianco ardente

d’una parete porosa come la pasta del pane

superficie di un medioevo popolare

– Bari vecchia, un alto villaggio

sul mare malato di troppa pace –

un bianco ch’è privilegio e marchio

di umili – eccoli, che, come miseri arabi,

abitanti di antiche ardenti Subtopie,

empiono fondachi di figli, vicoli di nipoti,

interni di stracci, porte di calce viva,

pertugi di tende e di merletto, lastricati

d’acqua odorosi di pesce e piscio

– tutto è pronto per me – ma manca qualcosa.

(P. P. Pasolini, Un biancore di calce viva, in Poesie in forma di rosa)

Moving from Piazza Ferrarese we reach Piazza Mercantile.

The traveler can walk along via Venezia, called the “wall” of Bari that runs along the historical center and from which it is possible to enjoy the beautiful view of the promenade.

We cannot leave Bari Vecchia without visiting one of its most important monuments, the Basilica of San Nicola, which has been a privileged destination since the Middle Ages for many pilgrims.

Yesterday’s wayfarer only arrived after passing the Castle and the Cathedral through Via delle Crociate. Once he reached the current via Palazzo di Città, a street whose ancient name was Ruga Fragigena, that is, Francigena street, the square finally opens where the Basilica of San Nicola stands majestically, in its powerful Romanesque forms. In this route, we point out two different accesses: going along the promenade in the north direction, you can access the Basilica from a side road that allows you to get directly to the Basilica square. Alternatively, walking north on the wall you will find a staircase that allows direct access to Strada Palazzo di Città, or behind the Basilica.

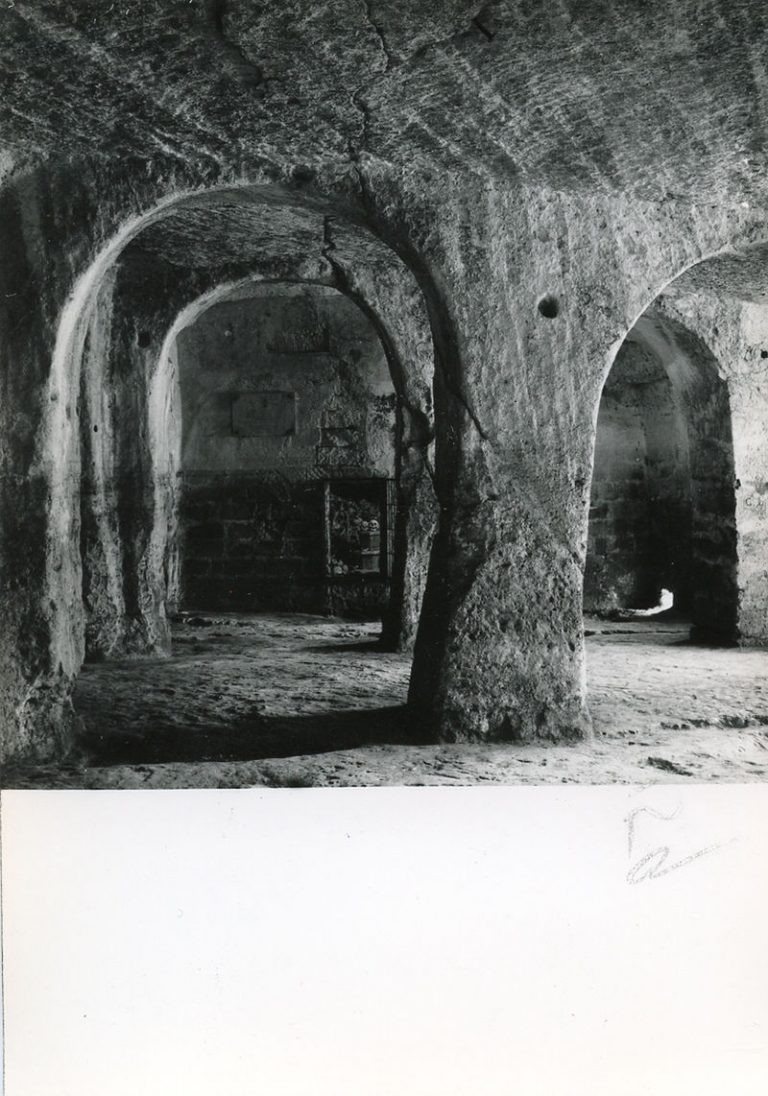

The Basilica is accessible from the side entrance in the cloister, via a ramp. Inside this monument, in the crypt with an oriental and Byzantine atmosphere, the relics of St. Nicholas are preserved, revered by both Catholics and Orthodox; from the remains of his body, stolen by a group of sailors from Bari in 1087 from the city of Myra, it is believed that he still oozes a miraculous liquid with healing powers, called manna. Pilgrims’ travel diaries speak about it. Anselmo Adorno, a cultured Flemish nobleman, after coming back from his pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the second half of the 15th century, visits the Nicolaian basilica and gives us a ‘devoted’ description:

Adorno writes:

Le spoglie [di San Nicola] riposano in un’arca di marmo sotto il grande altare della cripta. La parte anteriore dell’altare è istoriata con immagini sbalzate in argento. Sempre sul fronte dell’altare c’è una porticina attraverso cui, da un foro che penetra all’interno del monumento, ove una lampada accesa pende da una catena d’argento, si distinguono le reliquie di S. Nicola. Da esse dicono che scaturisca un olio santo, ovvero un liquido con cui vengono unti occhi e fronti delle persone nelle festività solenni, così come fu nel tempo in cui noi fummo a Bari, cioè nel giorno di S. Nicola.

- Adorno, Itinéraire d’Anselme Adorno en Terre Sainte)

Itinerary

3

ACCESSIBILITY: absence of barriers for mobility

USABILITY: multisensory panel with audiovisual and tactile information

ACCESSIBILITY: no mobility barriers (ground floor and first floor)

USABILITY: audio guides; lift to access the upper floor

At the end of Via Sparano, turning left we take Corso Vittorio Emanuele and after a while on the left we find the Piccinni Theater.

The theater has recently been renovated and reopened to the public; on occasion of the inauguration the project Il Teatro Piccinni was presented … in all senses, realized thanks to the collaboration with the Rotary Club Bari Sud and the Rotary Club Venezia, with the sponsorship of UICI (Unione Italiana dei Ciechi e degli Ipovedenti) of the Province of Bari. The project led to the creation of a multisensory panel with visual, tactile and audio information which recounts, through the use of different languages, the characteristics of the building and offers useful information on the historical-cultural value of the theater; the panel is positioned at the main entrance and close to the secondary entrance, used in particular by people with motor disabilities.

Continuing on Corso Vittorio Emanuele and turning on the right near the Palazzo della Prefettura you get to the Norman Swabian Castle, a monument with accessibility standards which we recommend.

When talking about the most authentic corner of Bari Vecchia, the writer Lalla Romano says:

Penetriamo, per vicoli, nella città vecchia; viva e insieme remota, piena di infanzia.

Una piazzetta irregolare, strana, meravigliosa. Da un lato casucce in vario movimento e colori, un po’ come una scena (in terra sono sparsi resti di ortaggi, dopo il mercato), e di fronte la mole austera, semplice, chiara, di un castello di pietra. Castello svevo (o normanno: nomi che fanno sognare). Sulla prima rampa corrono giocando, gridando, bambini. Il Duomo incombe con la sua maestà su un’altra piazzetta paesana, piccola, allegra. (L. Romano, Diario di Grecia)

Going along the perimeter of the castle, on the right you can see the Cathedral of San Sabino.

The entrance to the Cathedral is possible via a ramp located on the side. Access to the basement is also guaranteed.

We leave Bari and its monuments to continue the itinerary southwards, along the Adriatic coast, to stop in Polignano.

We recommend the traveler to spend a few days in this renowned tourist and seaside destination, built sheer above the sea on a deep ravine dotted with prickly pears, famous for giving birth to the singer Domenico Modugno. The landscape features of Polignano attracted the well-known documentary filmmaker Folco Quilici, who made a documentary film about Puglia in the seventies of the twentieth century, flying over the region from the sky aboard a helicopter. From that journey a book was then written, in four hands with the well-known anglist and intellectual Mario Praz. When Quilici flew over Polignano he immediately caught the characteristics that still make it a unique country:

Quilici writes:

Difficilmente si potrebbe immaginare un habitat che in sé riassuma più di questo un’immagine archetipa di un paese del sud, le case candide, il cielo azzurro, il mare blu. È nello stesso tempo difficile immaginare un habitat fuso con altrettanto vigore, ma al contempo con altrettanto rispetto, nella natura del luogo. (F. Quilici, Puglia)

However, it is not necessary to glide on Polignano by helicopter to appreciate its charm and grasp its characteristics – even by train, the Adriatic town does not disappoint the traveler.

Luigi Fallacara, who is an Italian poet and writer close to the movements of the Florentine avant-garde, originally from Bari, wrote the following as he describes Polignano:

Appena scesi dalla stazione, vi sorprende questa terra luminosa di mandorli in fiore. Le case bianche e rosa hanno un non so che di provvisorio e d’inattuale, come si gli uomini, ogni alba, le costruissero per una festa marina che debba durare un sol giorno.

A Polignano, l’ora è soltanto mattutina. […] Il mare è glauco e lontano, la brezza vi posa su un velo cinereo che l’appanna. Ogni suono è attutito, ogni aspetto vivente appare inconcepibile, […]. Parlare di bellezza qui è vano; la bellezza rapisce un sol senso. Qui bisogna parlare di immersione nell’elemento, di qualcosa che investe tutto l’essere e lo getta, con un balzo repentino, aldilà dalla storia degli uomini e dei tempi. Vi sentite affacciati ai primordi della terra, alle soglie dei mondi che tremarono di luce, dapprima, sotto le acque verdi, agli stupori degli essere che videro, per la prima volta, emerse dai ciechi fondi marini, le scogliere curvarsi aeree, dentro l’azzurro dei cieli. (L. Fallacara, Polignano)

Throughout the year, the Apulian town is animated by a lively cultural life that revolves around a rich program of events that are organized in the medieval village and numerous initiatives promoted by the Pino Pascali Museum of Contemporary Art; the large and panoramic rooms of this museum structure fully satisfy all the accessibility criteria. The museum, which is spread over three floors, one of which is underground, is equipped with an elevator, an external ramp and health facilities dedicated to the specific needs of people with limited mobility. However, we point out the absence of specific aids for blind or partially sighted people.

Leaving the museum behind us, we recommend a walk along the seafront using the accessible road that takes the traveler to Largo Ardito from which it is possible to enjoy a fantastic panorama.

From this point the traveler who wishes can continue the walk to the historical center and go into the alleys. For example, once you arrive in Piazza Aldo Moro, you can cross the Arco Marchesale and continue up to the balcony that opens to the left of the Chiesa Matrice, which is dedicated to S. Maria Assunta and is accessible from a side entrance.

From Polignano we move towards Castellana. The town is best known for the complex of its natural caves, the longest underground network in Italy. As part of the 100% accessible Caves project, a team of specialized operators guarantees the opportunity to live in safety the experience that this incredible underground environment is able to give, taking into account the different special needs of travelers. Excursions are organized for people with physical, mental, intellectual, relational and sensory disabilities. It should be noted, however, that due to the structural characteristics, accessibility is guaranteed in some sections only for wheelchairs with a maximum width of 65 cm. The visit has dedicated times and methods and the traveler can either choose a short itinerary, lasting about 90 minutes, or a more demanding complete itinerary (up to the White Grotto) lasting about 3 hours. A sign-language video guide of the Caves itinerary has also been devised, to allow deaf travelers to take advantage of this service. All the information and contacts for any visits are available on the Grotte di Castellana website (reservations are required).

Le us tell you the story of these caves by considering the Piacenza writer Vincenzo Piovene, who in the mid-1950s published his famous Journey to Italy, a reportage to discover Italy in the years immediately preceding the economic boom.

Piovene wrote:

Le grotte di Castellana, in provincia di Bari a poca distanza dal mare, ma presso i confini di quella di Taranto, possono servirci da introduzione alla parte più bella della Puglia. Le Murge, altopiano roccioso nella parte elevata, nella parte più bassa ricoperto di terra fertile che permette le coltivazioni, sono il nucleo centrale della Puglia, tra il Tavoliere ed il Salento. Questo è il Carso del Sud; Grotte e spelonche lo traforano; più famosa di tutte quella di Castellana. Per quanto cronache imprecise ci parlino di esplorazioni compiute da gente del luogo nel Sette e nell’Ottocento, fino a vent’anni fa di queste grotte era nota soltanto una voragine rotonda, quasi un gigantesco pozzo, circondato dai lecci, che si apriva sulla collina. Superstizioni popolari vi collocavano l’inferno. Franco Anelli, dell’Istituto Italiano di Speleologia che allora aveva sede a Postumia, calatosi nella voragine nel 1938, trovò nella parete il corridoio con il quale si inizia l’itinerario sotterraneo, e cominciò l’esplorazione scientifica. Le grotte furono sistemate l’anno seguente, ma il vero inizio della loro celebrità è del 1949. In anni ancora più recenti, coi fondi della Cassa del Mezzogiorno, ebbero l’attrezzatura di oggi per il turismo e per la ricerca scientifica, l’edificio per la direzione, il Museo di Speleologia, gli accessori. Ho percorso con Franco Anelli, che adesso ne è il direttore, queste che sono di gran lunga le più belle grotte italiane. Il confronto con quelle di Postumia veniva con lui naturale. Il regno sotterraneo di Castellana, rispetto a quello di Postumia, ha sale forse meno ampie, ma corridoi più lunghi, più misteriosi e capricciosi, più sfarzo di alabastri, più varietà di stravaganze, piogge di stalattiti ancora più fitte, ed una profusione di cortine diafane, dove la pietra diventa così sottile da imitare la muffa e il velo; e soffitti di stalattiti di impareggiabile bianchezza. (G. Piovene, Viaggio in Italia)

ACCESSIBILITY: lift

USABILITY: the route is guaranteed for 65 cm wide wheelchairs. Audio guides, tactile visits, sign-language video guide

From Castellana, our itinerary now stops in Alberobello, the famous trulli town that is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a pleasant surprise in terms of hospitality and accessibility.

The literary guide of this part of our itinerary will again be Pier Paolo Pasolini who defines Alberobello as a country with perfect shapes:

[…] un paese perfetto la cui forma si è fatta stile nel rigore in cui è stata applicata. Dal primo muro all’ultimo, non un corpo estraneo, non un plagio, non una zeppa, non una stonatura. L’ammasso dei trulli nel terreno a saliscendi si profila sereno e puro, venato dalle strette strade pulitissime che fendono la sua architettura grottesca e squisita. […] Ogni tanto nell’infrangibile ordito di questa architettura degna di una fantasia, maniaca e rigorosa – un Paolo Uccello, un Kafka – si apre una frattura dove furoreggia tranquillo il verde smeraldo e l’arancione di un orto. E il cielo…È difficile raccontare la purezza del cielo […] un cielo inesistente, puro connettivo di luce sulle prospettive fantastiche del paese. (P. P. Pasolini, I nitidi trulli di Alberobello).

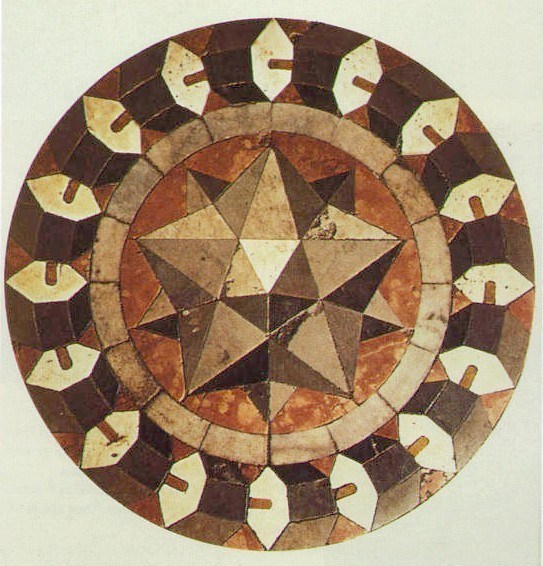

The trullo, a distant heir of the typically Mediterranean construction model of thòlos, has a characteristic truncated-conical shape. It is a dry construction that was born from the need of farmers to make the stony limestone soil of the area cultivable. Farmers were forced to remove the abundant layers of rock in the soil and decided to use them as a building material. Hence, as observes the poet from Montemurro in Lucania, Leonardo Sinisgalli, «l’astuzia contadina da un segreto o da un caso trasse una regola. Che per adattarsi alle virtù del materiale riuscì a sottrarsi al rigorismo della geometria». (L. Sinisgalli, Prefazione alla La valle dei trulli di M. Castellano)

About twenty years before Pasolini’s trip from Puglia, Tommaso Fiore, an intellectual engaged in denouncing the poor living conditions of the peasant classes, spoke of the trulli of Alberobello. In his Lettere pugliesi, collected in Popolo di formiche, he writes:

Avrai sentito parlare anche a Torino dei nostri trulli, diamine! […] sono minuscole capanne tonde, dal tetto a cono aguzzo, in cui pare non possa entrare se non un popolo di omini, ognuna con un piccolo comignolo ed una finestrella da bambola, e con quella buffa intonacatura sul cono, che è la civetteria della pulizia, e dà l’impressione di un berretto da notte ritto sul cocuzzolo d’un pagliaccio, con anche, per soprammercato, una croce o una stella in fronte, dipinta con calce! (T. Fiore, Un Popolo di formiche)

Pasolini is astonished at this bizarre popular architecture and states:

Di un trullo isolato si potrebbe parlare solo con i termini della cristallografia. Tutti corpi solidi vi sono fusi mostruosamente per dar forma a un corpo nuovo, delicato, leggero. I tetti a punta, di un nero cilestrino, si staccano improvvisi da questa base contorta e armoniosa, per riempire il cielo di magiche punte. (P. P. Pasolini, I nitidi trulli di Alberobello).

The traveler will be able to discover the charm of this Apulian country, unique in its kind – although today partially compromised by the numerous kitsch souvenir shops for the use and consumption of unsustainable tourism -, along the accessible sidewalks that start from the shoulders of the Basilica and lead in the pedestrian area of the center, up to Piazza del Popolo where you can enjoy the panoramic view of the Monti district, the most characteristic part of Alberobello.

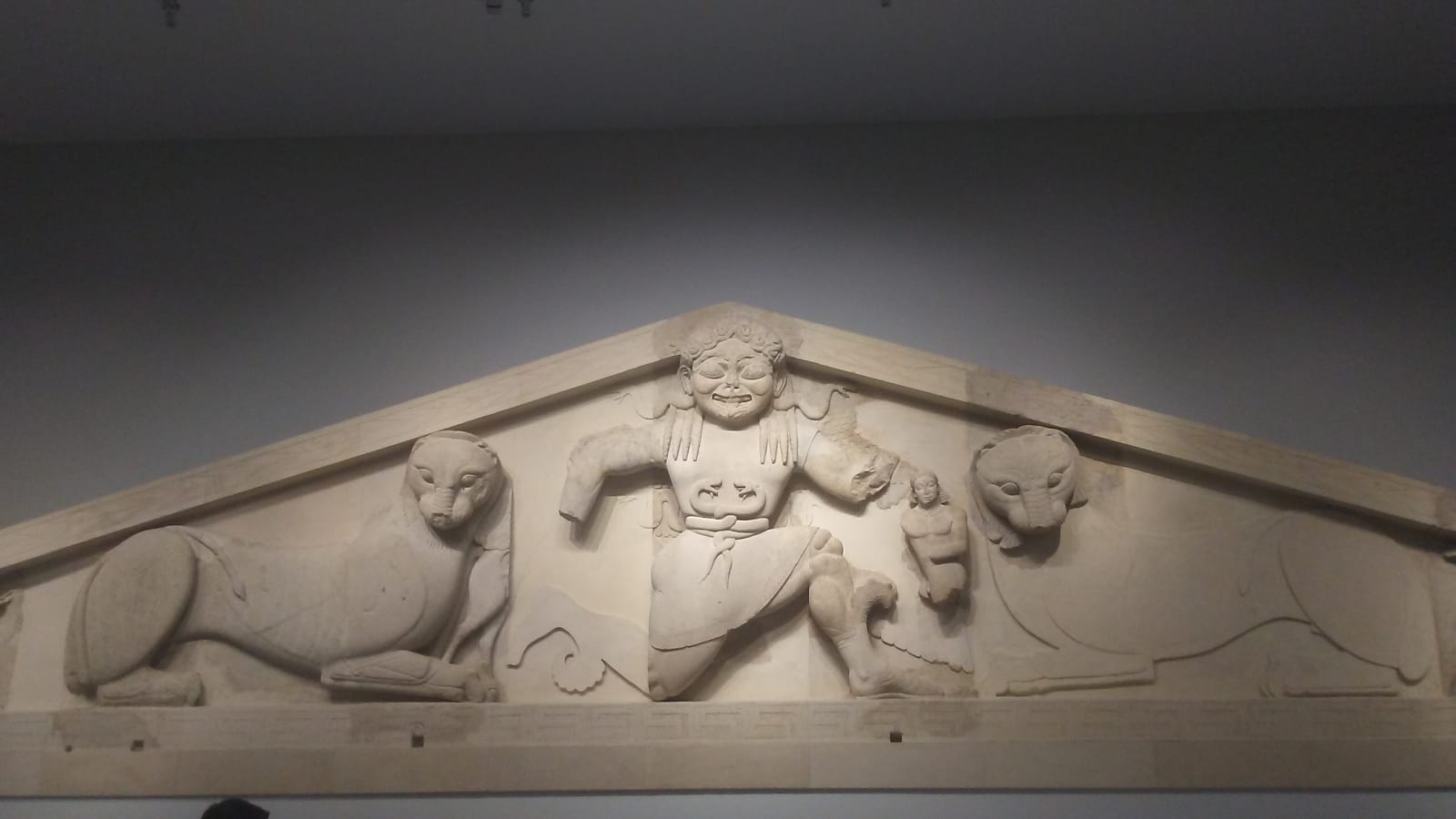

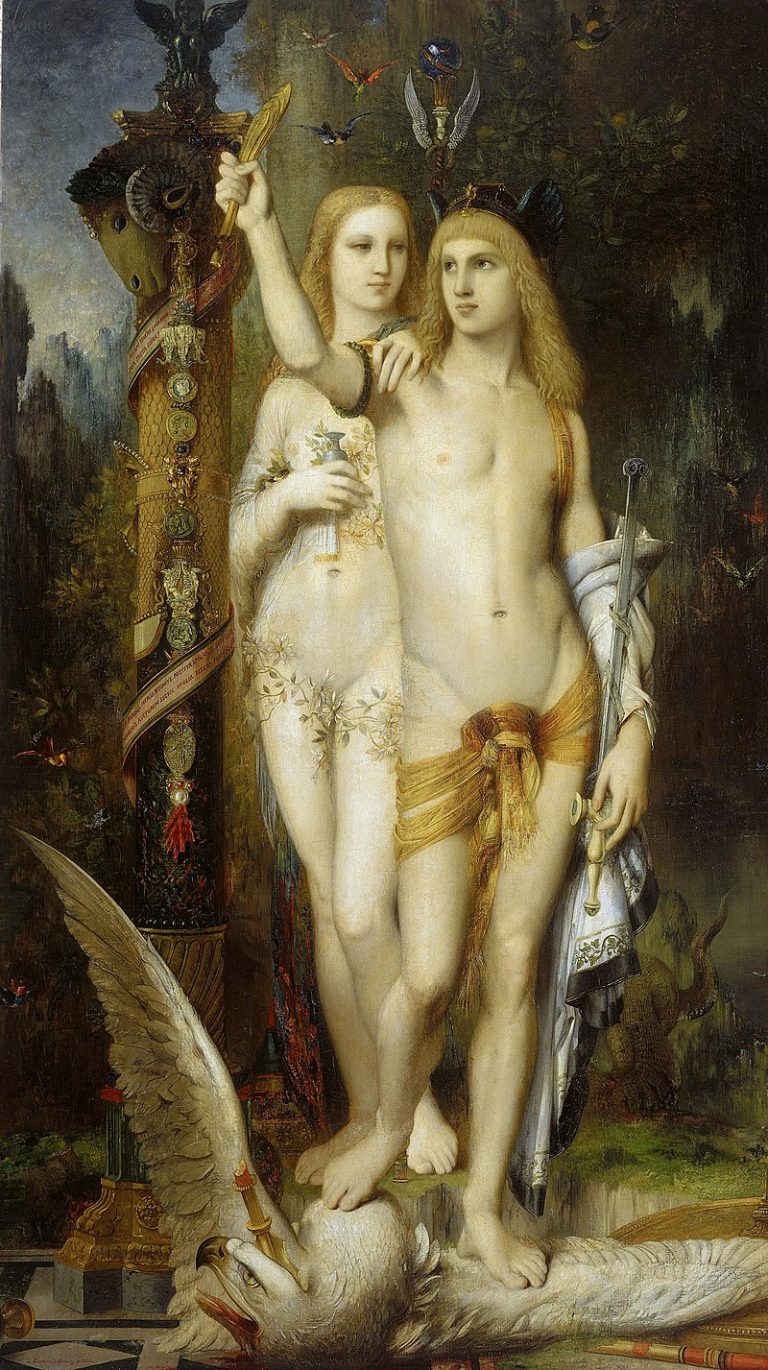

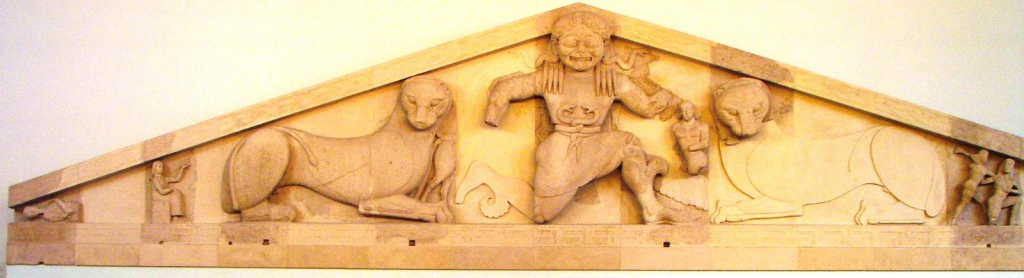

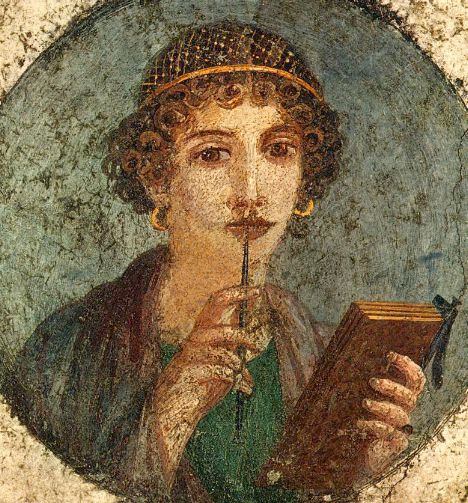

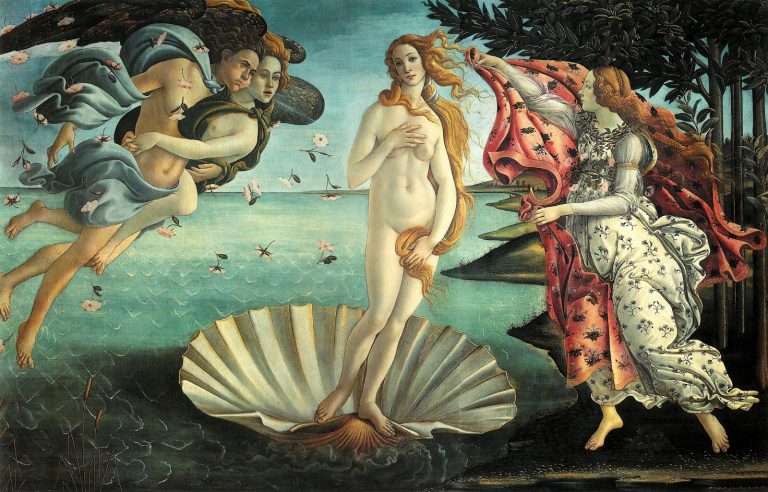

From the village of the trulli our itinerary proceeds to the next stop: Taranto. A city of a thousand contradictions marked dramatically by the events linked to the ILVA steel plant which with its poisonous fumes ended up obscuring its more sunny and bright face. The traveler, however, can find the signs and testimonies of marvelous Taranto along the vast Lungomare of the city, which is famous for its sunset views that enchanted poets and writers and, above all, he can visit its archaeological museum: the Marta.

This museum structure is fully accessible, thanks to the external ramp and the elevators located inside. Although there are no specific aids for conditions of sensory disabilities, after communication via email to man-ta@beniculturali.it, it is possible to access the museum rooms accompanied by your guide dog or other pets whose support is certified to therapeutic treatments (pet-therapy).

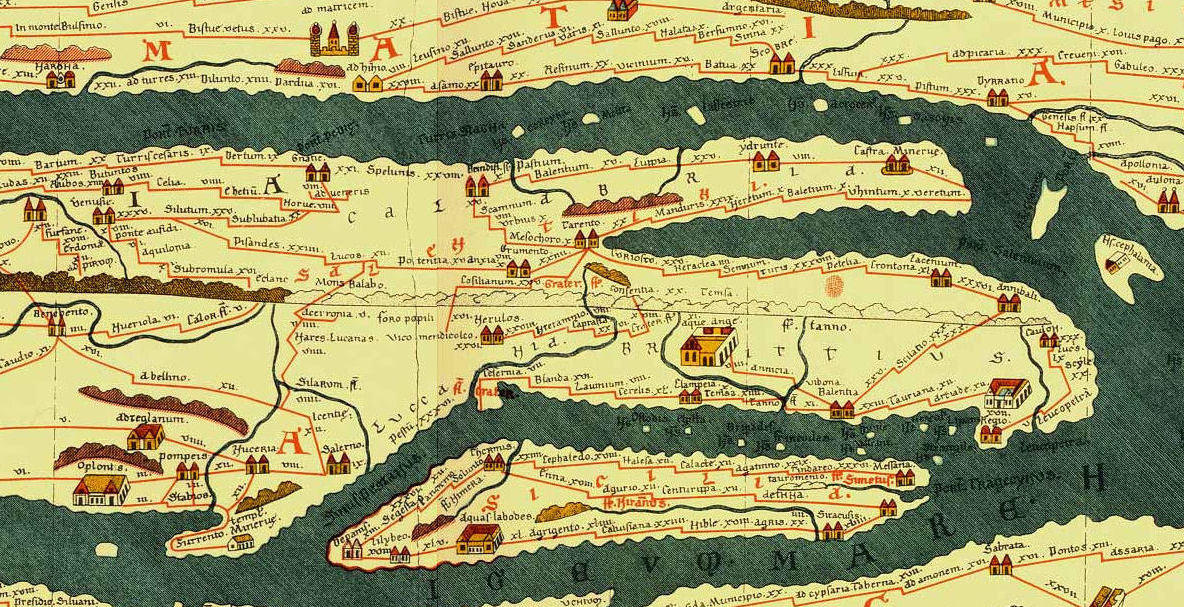

We enter its rooms ideally following Paolo Rumiz, a famous writer and journalist who arrived in Taranto in 2015, following the route of the ancient Via Appia on foot. The story of this incredible journey has become a book, entitled Appia which can be used as a guide and point of reference. Rumiz writes:

[…] è vietato andarsene da Taranto senza aver visto il museo archeologico. All’ex-convento dei frati alcantarini si deve andare semplicemente perché ce lo ordina la bellezza, e la bellezza se ne frega se Roma è distratta e lontana, se a Taranto non arriva nessun Frecciarossa e non c’è aeroporto. […]

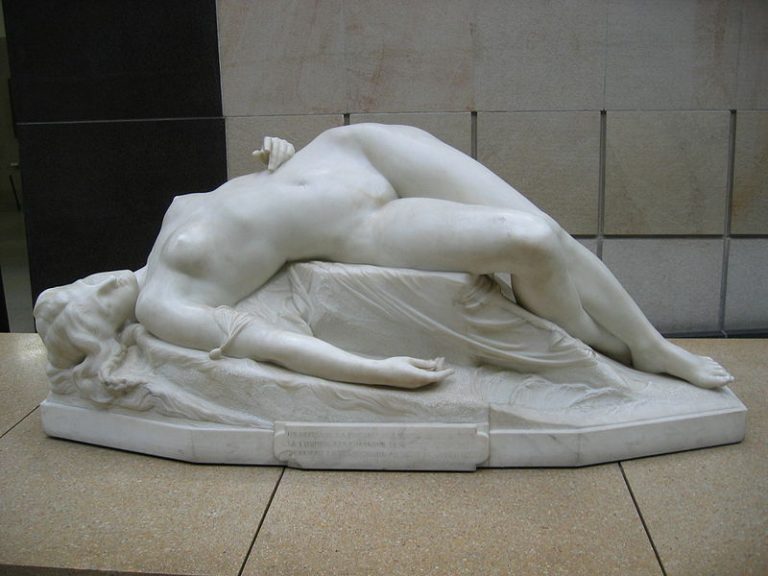

In quelle sale venerabili abita una delle meraviglie d’Europa. Un’antichità che non è marmo freddo ma scintillio di ori e argenti, gioielleria greca sepolta e riemersa dalle necropoli del IV e III secolo avanti Cristo. Taranto delle grandi botteghe degli orafi, Taranto trionfo di un universo femminile che Roma è ancora lontana dal concepire. Taranto dagli orecchini a navicella tintinnanti di pendagli, dalle foglie d’alloro e dai petali rosa in lamina d’oro zecchino. Taranto degli anelli, dei monili, delle teste di leone, fucina di smalti favolosi, cristalli di rocca, granulati d’oro, anelli, cammei e raffinati sigilli. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

From Marta, crossing Piazza Garibaldi and taking Via D’Aquino, the traveler can easily get to the Lungomare, from which it is possible to admire the beautiful Aragonese Castle.

Unfortunately the structure is not completely accessible; we would like to point out for anyone wishing that visits to the facility are carried out free of charge at specific times.

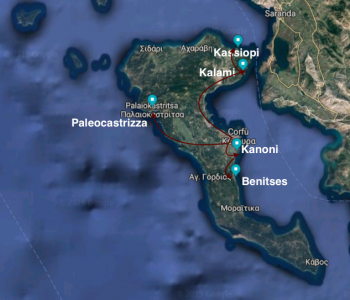

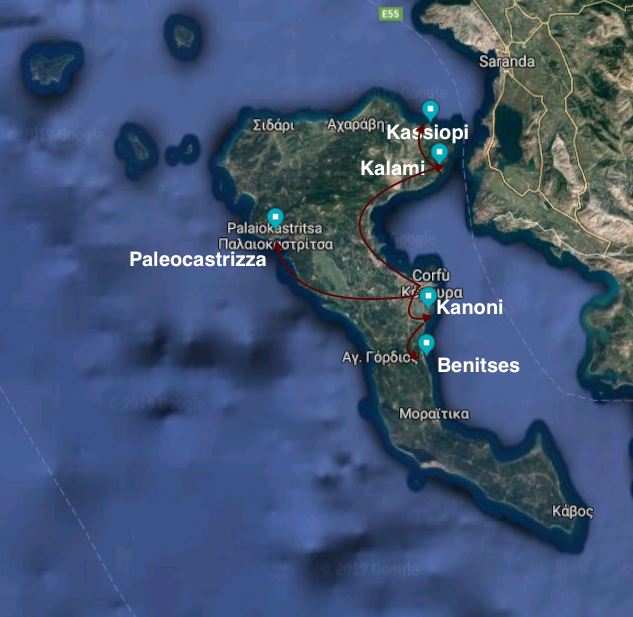

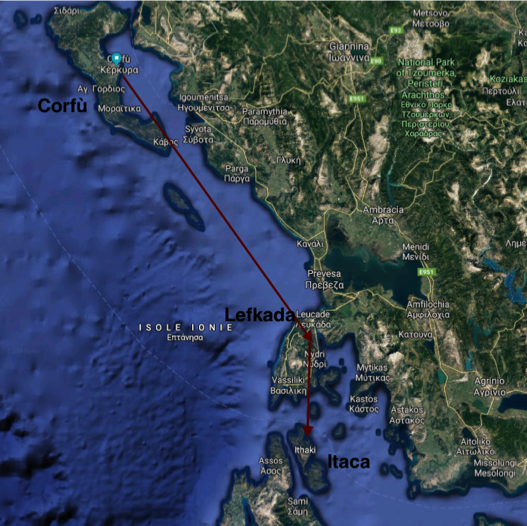

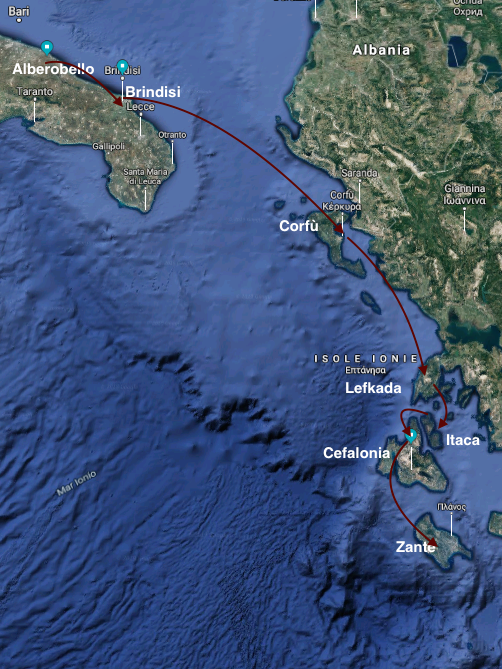

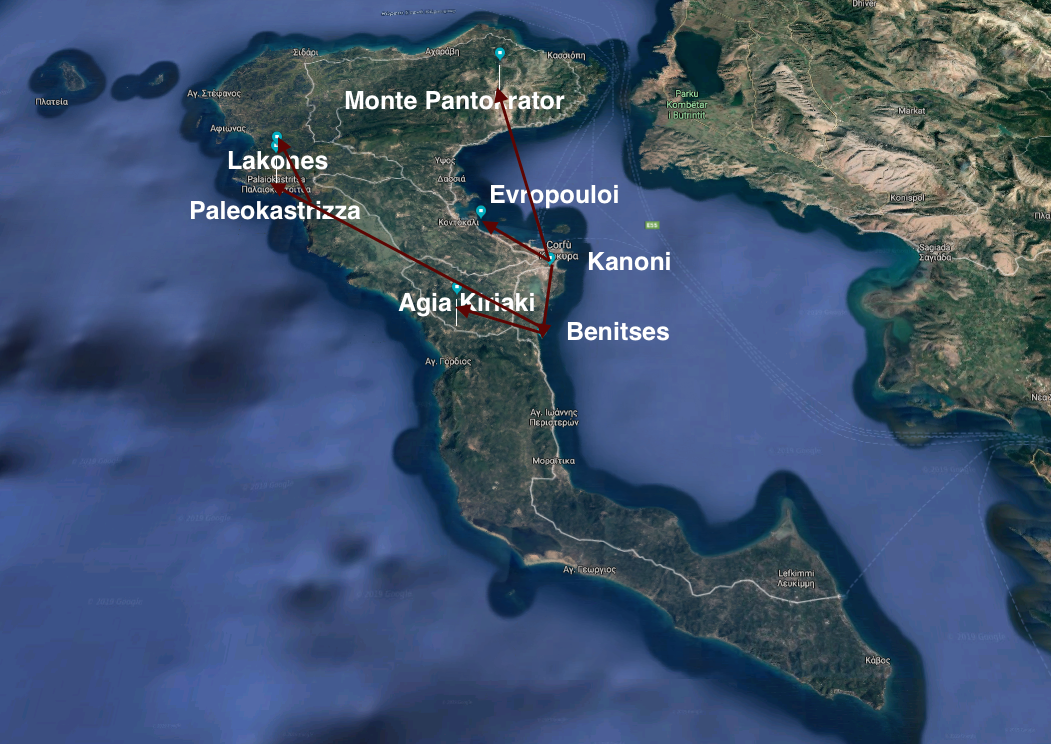

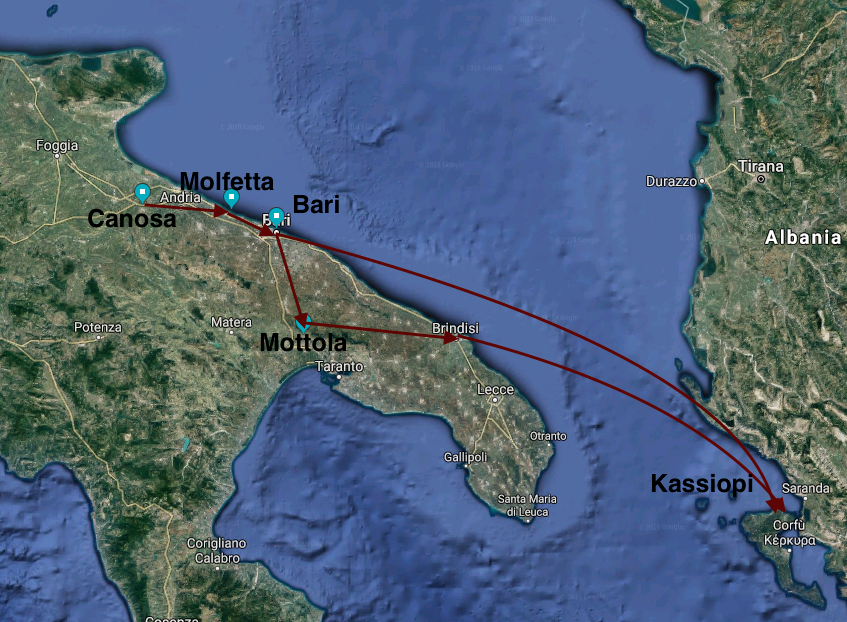

We leave Taranto and Puglia to continue the itinerary on the island of Corfu, in the Ionian Islands of Greece. Today there are many ferry companies that depart from Bari or Brindisi equipped with all the comforts needed to meet the needs of every type of traveler. However, it is preferable to travel by plane; it should be said at the outset that due to the shape of the Ionian Islands, they are not always easily visited or accessible. Notwithstanding this, in recent years, especially in Corfu, initiatives have been undertaken that have made some of the most beautiful beaches accessible to everyone, through easy access to the sea thanks to floating ramps. We point out in particular the beaches of Benitses, which will also be one of the stages of our itinerary on the island.

The discovery of the beauty of Corfu begins for all travelers from the sea, when they are about to land on the island and from the deck of the ship or from the window of their cabin they begin to glimpse the contours.

Gerald Durrell, a famous English naturalist, as a child, moved with his family to the island, a few years before the outbreak of the Second World War. The memories of that incredible experience have inspired his very successful book entitled My family and other animals, from which an appreciated television series has also been drawn recently. In the opening pages of his bestseller he describes the moment when Corfu finally appears on the horizon. His words are well suited to describe what the traveler will see, as he reaches the island and, at dawn, faces the ferry pier:

[…] Il mare gonfiava i suoi azzurri e levigati muscoli ondosi mentre fremeva nella luce dell’alba, e la schiuma della nostra scia si allargava delicatamente dietro di noi come la coda di un pavone bianco, tutta scintillante di bollicine. Il cielo era pallido, con qualche pennellata gialla a oriente. Davanti a noi si allungava uno sgorbio di terra color cioccolata, una massa confusa nella nebbia, con una gala di spuma alla base. Era Corfù, e noi aguzzammo gli occhi per distinguere la forma delle sue montagne, per scoprirne le valli, le cime, i burroni e le spiagge, ma non ne vedemmo che i contorni. Poi, tutt’a un tratto, il sole spuntò sull’orizzonte e il cielo prese il colore azzurro smalto dell’occhio della ghiandaia. Le infinite e meticolose curve del mare si incendiarono per un istante, poi si fecero d’un intenso color porpora screziato di verde. La nebbia si alzò in rapidi e flessibili nastri, ed ecco l’isola davanti a noi, le montagne come se dormissero sotto una gualcita coperta scura, macchiata in ogni sua piega dal verde degli ulivi. Lungo la riva le spiagge si arcuavano candide come zanne tra precipiti città di vivide rocce dorate, rosse e bianche. Doppiammo il promontorio, le montagne scomparvero e l’isola si trasformò in un declivio dolce, macchiato dall’argentea e verde iridescenza degli ulivi, interrotta qua e là dal dito ammonitore di un cipresso stagliato contro il cielo. (G. Durrell, La mia famiglia e altri animali)

To the traveler who is instead reaching Corfu by plane the marvellous arrival on the island will not appear less beautiful, as the famous art critic Mario Praz described it in the 1930s during one of his travels to Greece:

Nuvole dai riflessi di piombo strisciano sopra Corfù. I biancastri promontori dell’isola sfilano in basso, a sinistra. Oltre la plumbea nube si scopre un promontorio azzurro nel sole. Giochi d’ombre e di luce sulla bella isola verde, un lembo di sabbie fulve a occidente, sul mare aperto; e infine la città con le sue fortezze, i suoi grigi tetti antichi e i suoi cipressi, e, di fronte alla rada, un’isoletta simile a una distesa pelle di toro. Tra noi e la terraferma passano veli irridescenti; in uno strappo si mostra un quieto laghetto tra i monti.

Ci abbassiamo; il motore tambureggia, l’idrovolante si tuffa sotto ondate di nuvole, tra i monti dell’isola. Per un momento tutto è opaco intorno; poi uno squarcio di turchino intenso, e questa terra che mi lascio alle spalle, con queste isolette che ne sono la fuggente retroguardia, è l’ultimo lembo di suolo greco. Ma non è un saluto da dio che mi viene alle labbra. Perché la Grecia è più grande; noi occidentali la portiamo nell’anima anche sotto le più inospiti latitudini. (M. Praz, Viaggio in Grecia)

Once disembarked, the elegant and at the same time colorful historical center of Corfu, which has been inserted among the UNESCO world heritage sites, will not leave the traveler indifferent; we recommend to stop in one of the many cafes that are located on Liston, the long road arcade built by the French in the image of Rue de Rivoli in Paris on the large and verdant Piazza della Spianada.

Here it was not unusual until a few decades ago to come across cricket matches, a very popular sport in Corfu, brought by the British during the period of their protectorate on the island.

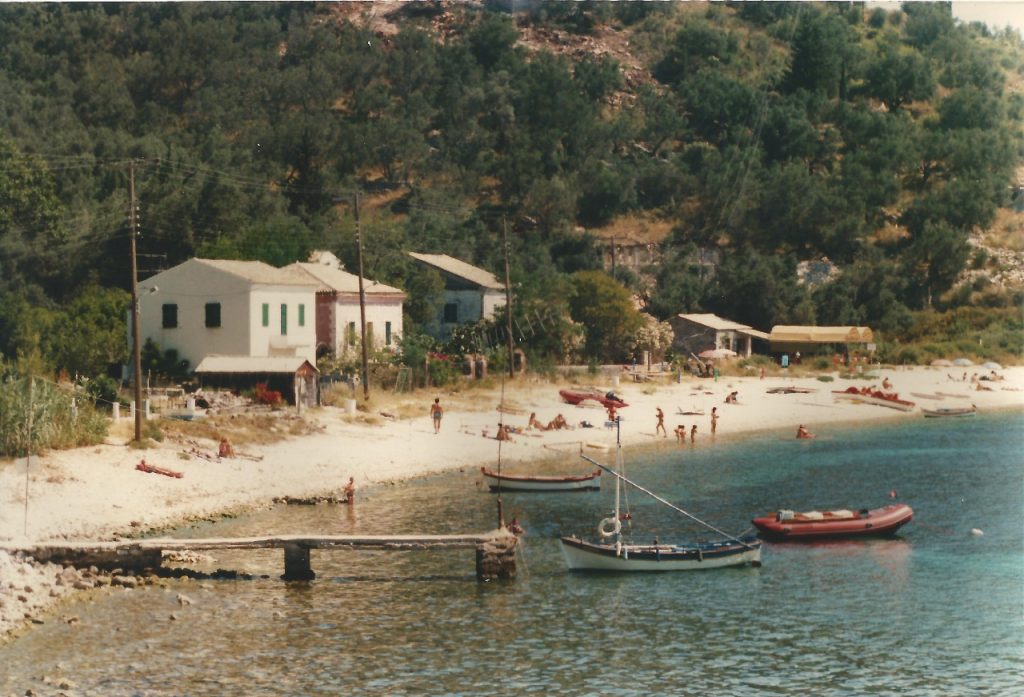

We point out that not far from the city of Corfu, just 14 kilometers south, there is the village of Benitses, a popular tourist destination and a renowned seaside resort which is equipped to allow travelers with walking difficulties to take advantage of its enchanting beaches. Special ramps are in fact available to allow independent access to the sea; there are also bathrooms, showers and dedicated lockers.

This area is known for its beautiful sandy and pebbly beaches, the traveler will also be able to discover it through the words of Gerald Durrell who, right between these coves and inlets, used to spend long afternoons in the company of his trusted dog Roger:

Un pomeriggio, in una calura languida in cui sembrava che tutto dormisse all’infuori delle cicale, Roger e io ci incamminammo […].

L’isola sonnecchiava sotto di noi, scintillante come un acquerello appena dipinto, nella foschia dell’afa: ulivi grigioverdi, cipressi neri, rocce multicolori lungo la costa, e il mare levigato e opalescente d’un azzurro martin pescatore, verde giada, con qualche lieve increspatura sulla sua superficie liscia dove si incurva intorno a un promontorio roccioso e fitto di ulivi. Proprio sotto di noi c’era una piccola baia lunata col suo bordo di sabbia bianca, una baia così bassa e con fondo di sabbia così abbagliante che l’acqua era di un azzurro pallido, quasi bianco.

This itinerary ends in the crystalline sea of Corfu, a sea over whose waters myths, heroes and traveling writers have traveled.

|

1. Railway Station ACCESSIBILITY: barrier-free route (with ramp and elevator), tactile route from the station entrance to the platforms USABILITY: sound and visual information systems available to the public |

|

2.Palazzo Mincuzzi ACCESSIBILITY: absence of barriers for mobility USABILITY: internal lift to access upper floors |

|

3.Corso Vittorio Emanuele |

|

4. Teatro Margherita ACCESSIBILITY: external ramp |

|

5.Lungomare Nazario Sauro |

|

6. Pinacoteca Provinciale ACCESSIBILITY: lift inside the building to access the Pinacoteca USABILITY: audio guides |

|

7. Pane e Pomodoro Beach ACCESSIBILITY: concrete walkway with steel handrail to access the shoreline USABILITY: accessible cabin / dressing room |

|

1.Stazione ferroviaria ACCESSIBILITÀ: percorso senza barriere (in piano, con rampa, con ascensore), percorso tattile dall’ingresso della stazione ai binari FRUIBILITÀ: sistemi di informazioni al pubblico sonori e visivi |

|

2. Palazzo Mincuzzi ACCESSIBILITÀ: assenza di barriere per la mobilità FRUIBILITÀ: ascensore interno per accedere ai vari piani |

|

3. Corso Vittorio Emanuele |

|

4. Piazza Ferrarese |

|

5. Piazza Mercantile |

|

6. Via Venezia/la Muraglia Barese |

|

7. Basilica di San Nicola ACCESSIBILITÀ: rampa esterna laterale |

|

1.Stazione ferroviaria ACCESSIBILITÀ: percorso senza barriere (in piano, con rampa, con ascensore), percorso tattile dall’ingresso della stazione ai binari FRUIBILITÀ: sistemi di informazioni al pubblico sonori e visivi |

|

2. Palazzo Mincuzzi ACCESSIBILITÀ: assenza di barriere per la mobilità FRUIBILITÀ: ascensore interno per accedere ai piani superiori |

|

3. Teatro Piccinni ACCESSIBILITÀ: assenza di barriere per la mobilità FRUIBILITÀ: pannello multisensoriale con informazioni di tipo audio, visivo e tattile |

|

4. Castello Svevo ACCESSIBILITÀ: assenza di barriere per la mobilità (piano terra e primo piano) FRUIBILITÀ: audioguide; ascensore per accedere al piano superiore |

|

5. Cattedrale S. Sabino ACCESSIBILITÀ: rampa esterna laterale FRUIBILITÀ: possibilità di accedere al piano seminterrato |

POLIGNANO

|

1.Fondazione Pino Pascali ACCESSIBILITÀ: assenza di barriere per la mobilità FRUIBILITÀ: ascensore interno per accedere al piano inferiore |

|

2. Lungomare |

|

3.Vista Panoramica (Largo Ardito) |

| CASTELLANA/ALBEROBELLO | |

|

1.Grotte di Castellana ACCESSIBILITÀ: presenza di ascensore FRUIBILITÀ: il percorso è garantito per carrozzine di larghezza pari a 65 cm. Audioguide, visite tattili, videoguida LIS |

|

2.Alberobello |

TARANTO

|

1.Museo Marta ACCESSIBILITÀ: rampa esterna FRUIBILITÀ: ascensore interno per accedere ai piani superiori; possibilità di accesso con cane guida personale munito di guinzaglio e museruola o animale domestico con certificazione di supporto per cure terapeutiche (previa comunicazione) |

|

2.Lungomare |

CORFU

|

1.Corfu |

|

2.Benitses |

The rock church of San Nicola, one of the nicest among the «

The rock church of San Nicola, one of the nicest among the «