Itinerary-07-Arcadia-link-09

Itinerary-07-Arcadia-link-09

Pontikonisi island and Vlacherna monastery

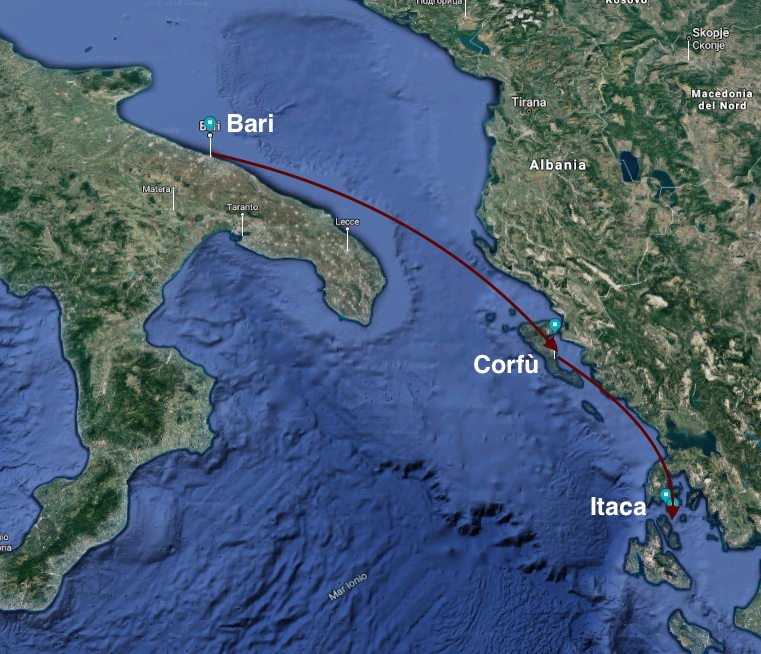

Kanòni Peninsula is located south of Corfu, within Garitsa natural bay, and offers one of the most enchanting views in the island: that of Vlacherna Monastery, which seems to rise in the middle of the sea. It is connected to the mainland through a narrow jetty, used as a dock for fishing boats. From this small dock it is possible to get to Pontikonisi islet, with its Byzantine chapel dedicated to Christ Pantokrator. Various literary and artistic echoes have been linked to this place. Many people have identified it with the subject of Böcklin’s painting, Isle of the Dead, whereas others with the island where Shakespeare set The Tempest; further, according to legend, it may be the Phaeacians’ ship Neptune turned into stone as an act of revenge.