Itinerary-12-Myths-link-04

Itinerary-12-Myths-link-04

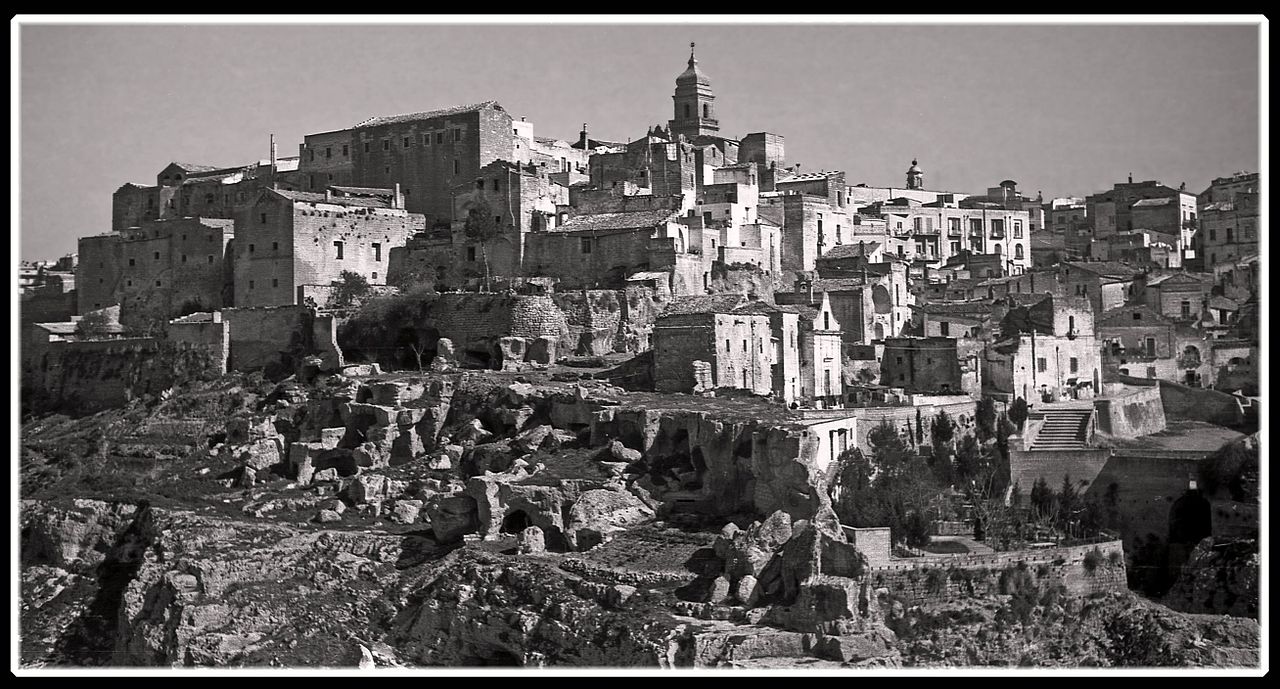

The Archaeological Park Of Botromagno

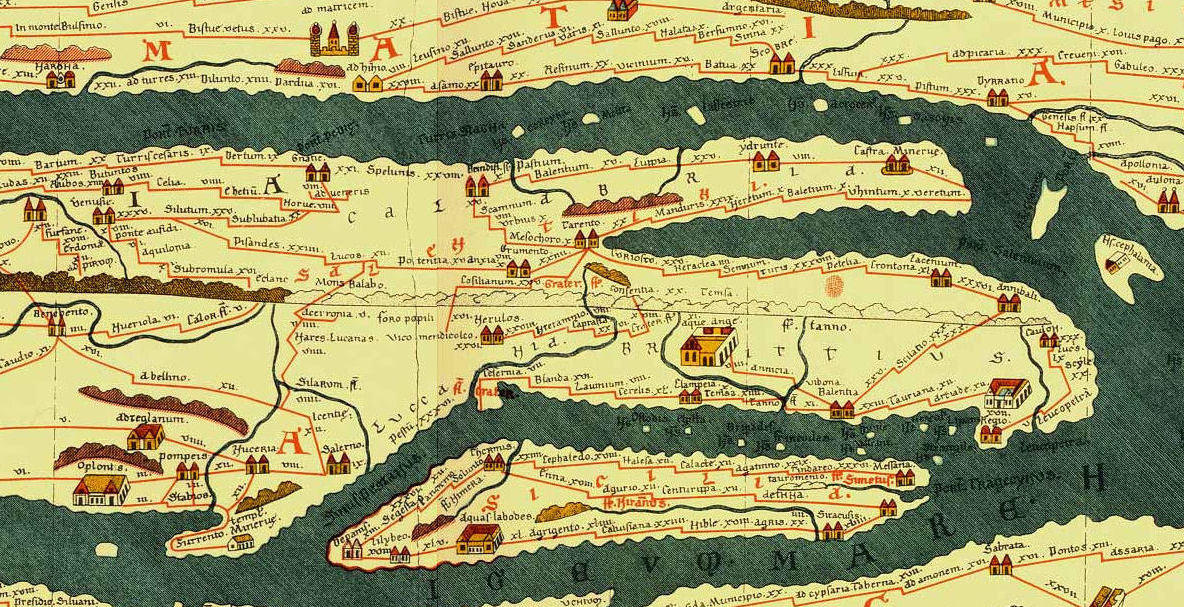

On the Botromagno Hill, which is about 400 meters high, it is possible to visit the remains of an ancient Peucetic centre, identified with the ancient Sides or Sidinion. Subsequently, the settlement became a Roman centre, probably Silvium, an important stop on the Appian Way. The area of considerable scientific interest could be one of the poles of archaeological excellence in Puglia, were it not for its state of abandonment and, in part, for the degradation in which the site is located. Paolo Rumiz wrote in 2015:

Una vecchia inchiesta, dal nome cinematografico di Stargate, svela che a Botromagno negli anni novanta sono stati effettuati importanti lavori per rendere accessibile ai visitatori quest’area archeologica unica al mondo. Ma l’intervento si è mangiato quindici miliardi di vecchie lire e non ha portato nulla, se si esclude la scomparsa del malloppo e una lite continua fra la direzione dei lavori e l’impresa esecutrice, che stava tirando in lungo come Penelope con la sua tela. Tutto è finito alle ortiche: il restauro delle tombe, gli itinerari di visita, la cartellonistica, il viale d’accesso, la riqualificazione di un edificio storico con foresteria e reception per i turisti. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

The objects coming from the Botromagno excavations are exhibited in the Ettore Pomarici-Santomasi di Gravina Museum, within the permanent exhibition entitled Aristocrazia e Mito.

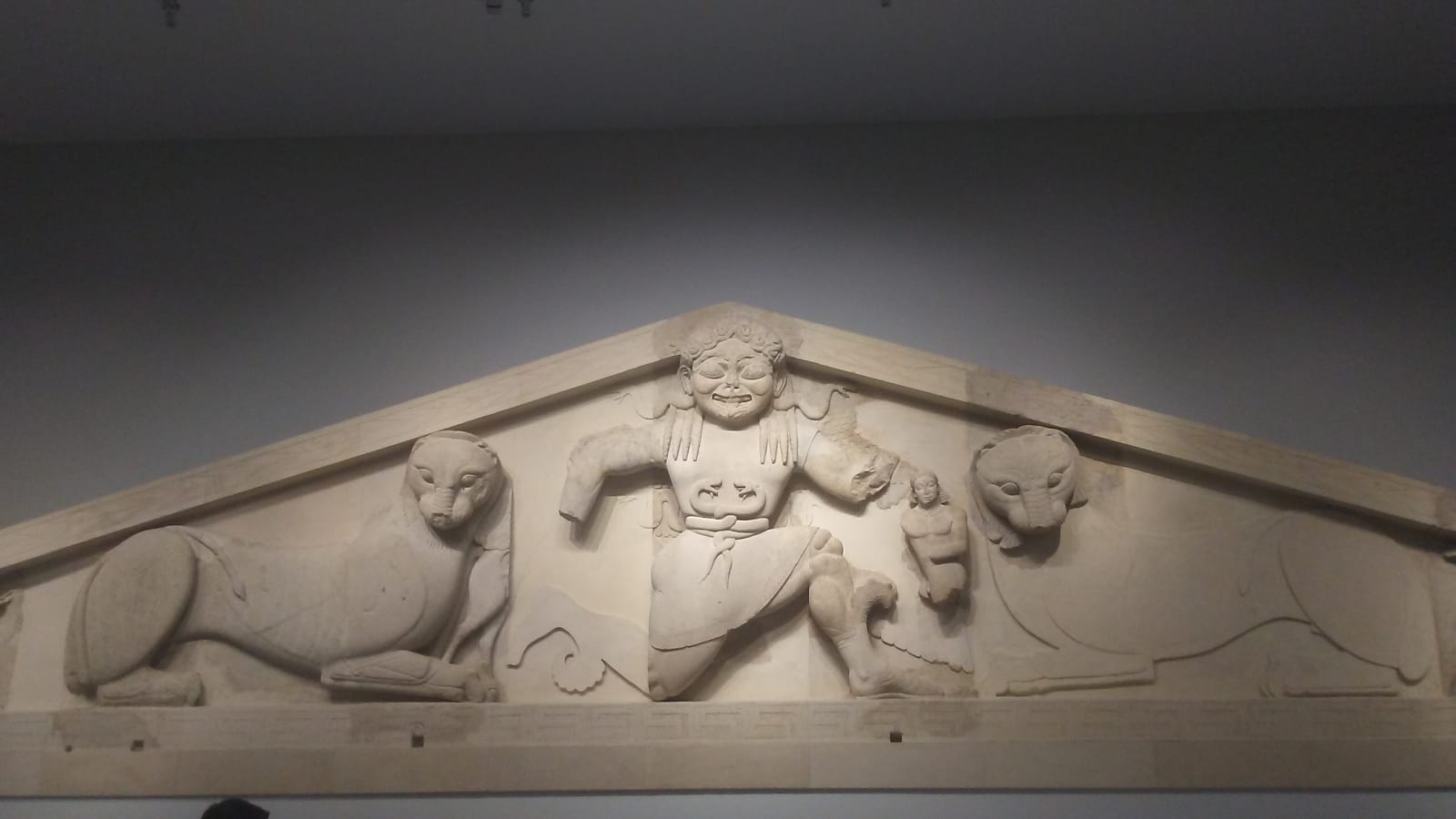

The oldest finds on display here are dated between the 7th and the 4th century BC and include fibulae, ornaments in amber, ivory and silver. Particularly interesting are the numerous red-figure vases from the 5th and 4th centuries BC coming from the sepulchral chambers of the alleged necropolis of Botromagno.

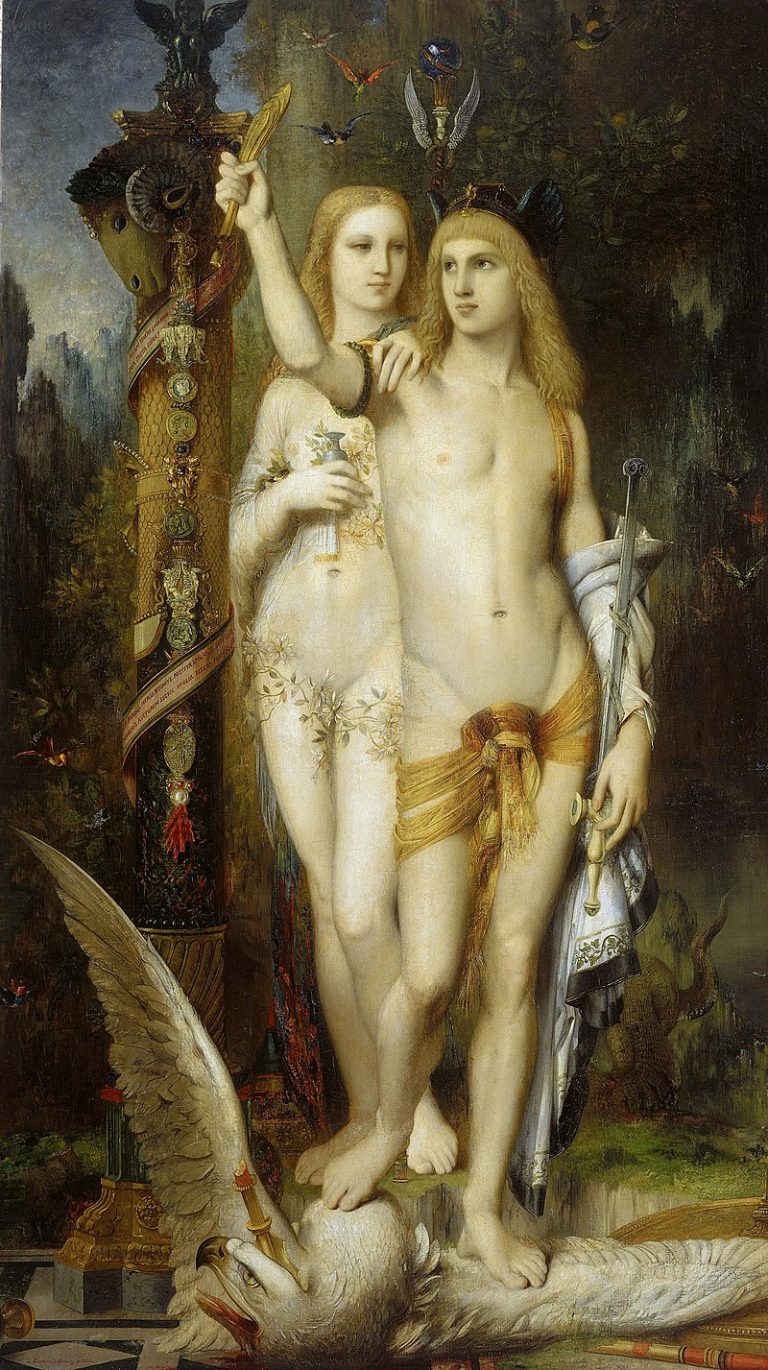

Among the numerous ceramic and fictile finds, due to its size and artistic beauty, a volute-shaped crater is attributed to the Painter of Boreas, which represents a scene from the myth of Iphigenia. Also other vases are decorated with scenes related to the Homeric world, confirming the uninterrupted artistic, commercial and political relations of Puglia with the Greek world. The exhibition at the Pomarici Santomasi Foundation only provides a glimpse of the richness of the archaeological heritage of this area of Puglia, which had been robbed over the last few centuries by grave robbers and improvised Indiana-Jones. What was saved from carelessness and thefts is also preserved in the Civic Archaeological Museum of Gravina, in Piazza Benedetto XIII.