Itinerary-14-Limits-link-03

Itinerary-14-Limits-link-03

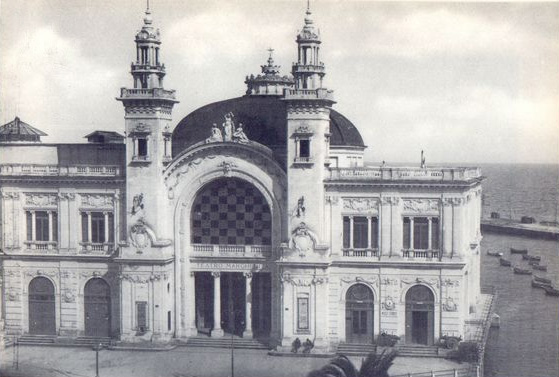

Teatro Margherita

Bari, Teatro Margherita, foto d’epoca- pubblico dominio-

Il Teatro Margherita, costruito nel 1893 in un’ansa del molo vecchio di Bari, si presenta come una struttura galleggiante edificata su palafitte. Danneggiato poco dopo la sua apertura da un incendio, venne riedificato e inaugurato nuovamente nel 1914. Fu costruito sul mare e collegato alla terraferma da un pontile, per aggirare il divieto di costruire nuovi teatri sul suolo comunale. L’edifico divenne sede di spettacoli di varietà alla moda, un vero e proprio cafè-chantant. Durante la seconda guerra mondiale, nel 1943, fu occupato dagli anglo-americani, che ne fecero la loro base logistica e un luogo di intrattenimento per le truppe, ribattezzandolo Garrison Theatre. Subì numerosi danni durante i bombardamenti del 1945 e fu ripristinato, ma esclusivamente come cinema, nel 1946. Negli anni ‘80 del Novecento, il Teatro Margherita venne chiuso e lasciato in stato di abbandono sino al 2005, quando, molto lentamente, iniziò una lunga stagione di restauri. Finalmente riaperto al pubblico, oggi è un’importante sede di mostre ed esposizioni di arte contemporanea.

Dal punto di vista architettonico, l’edifico all’esterno ha conservato molte delle caratteristiche originarie, con la facciata in stile liberty voluta dall’architetto Francesco de Giglio nel 1914. Un’ampia arcata vetrata, affiancata da torri terminanti in pinnacoli, delimita l’ingresso principale. Lungo tutta la facciata si alternano decorazioni di chiaro gusto novecentesco: festoni, maschere e ghirlande stilizzate. A coronamento dell’edificio si innalza una cupola ottagonale con terminazione a lucernario.

Per info e prenotazioni:

Piazza IV Novembre 70122 Bari

Tel.: +390805776200

Bari, Teatro Margherita prima dei restauri iniziati nel 2005, pubblico dominio

Bari, Teatro Margherita, dopo i restauri (foto i Ainars Brūvelis, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54351258)