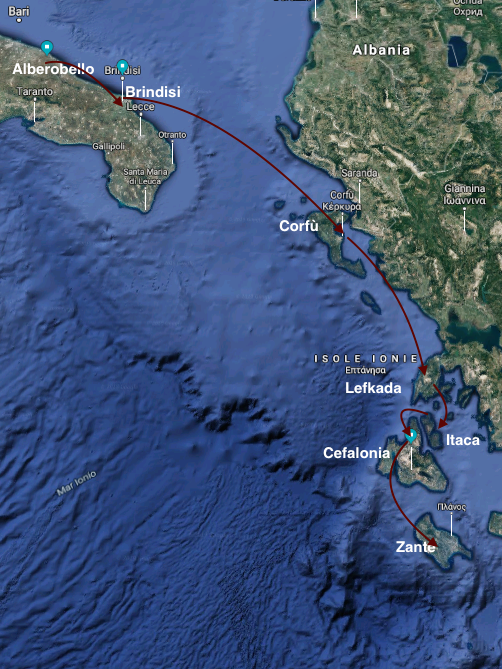

Alberobello, Brindisi, Corfu, Lefkada, Ithaca, Cephalonia, Zakynthos

In the 1970s, the British poet and writer Lawrence Durrell wrote The Greek Islands, the book on which this itinerary is grounded. It has never been translated into Italian in full, despite the awards won and its publishing success. It is not a common guidebook, but as «The Times» reviewers pointed out, it is a valuable volume, almost as one of the illuminated codices in the Patmos Monastery. It is a travel book written by a traveler who had just lived on the Greek islands and drawn inspiration for some of his literary masterpieces, Bitter Lemons and Prospero’s Cell. These texts are both a base for The Greek Islands, where the historical, artistic, mythological and sociological in-depth analysis of the classical Greek world and the modern age, along with clear and ironical writing, contributes to make it an ideal means of acquiring a special knowledge of the Greek islands today. It is a book conceived and written, as the author states, to answer the main questions the travelers may ask themselves when sailing from one Greek island to another: what would I have been glad to know about the island I reached? And what would I feel sorry to have missed while I was there?

Following this itinerary, contemporary travelers, guided by Lawrence Durrell’s words, personal reminiscences, evocative descriptions, British irony, and by his studies on Greek culture not only may answer the questions that led the author to write this book, but also may know the Ionian Islands through the eyes and sensibility of a great twentieth-century writer, who was enchanted by these lands so as to choose them as his own home for many years.

As every traveler knows, a trip starts before leaving, hence our itinerary, accepting our eminent guide’s suggestions, will start by inviting the reader to catch the signs coming from the journey, namely the ferry route that heads for the Ionian Islands, passing through Puglia, which has always been a route towards the East. Durrell writes:

The traveller, slipping southward along the heel of Italy, as if down a Christmas stocking full of small treasure-towns and unexpected monuments, first feels the intimations of a frontier coming to meet him a good way before he reaches the little terminal town of Brindisi. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands.)

In the 1970s, in Durell’s eyes, the south of Italy is still a wild area, dotted with charming green villages as the Itria Valley, «a strange and picturesque land of trulli, as they call those funny yet quite elaborate conglomerations of clay pots stuck together anyhow […]».

Hence we should wear that strange “Christmas stocking” and run throughout Italy – by train or by car – in order to get to Brindisi. The Apulian town, where the Via Appia once ended, marks the border between Italy and Greece. It is not a traditional frontier, a land boundary, but a sea border: it is the Adriatic Sea, then connecting to the Ionian Sea, that divides Puglia from Greece. Beyond that stretch of sea, the traveler does not know what to expect from the Greek islands that are waiting for him somewhere, concealed by the darkness of the night when he gets on the ferry connecting Puglia and Corfu. The traveler and the writer wonder:

What is that gives a frontier its magic? Not the fact that it is a territorial or political boundary, for these are artificial, dictated by history. A sudden change of scenery may be sometimes partly responsible, but often the change from one country to another is not accompanied by any change of flora and fauna (Italy to Greece, for example, France to Spain). Perhaps it is language that gives to the crossing of a frontier its definitive flavour of voyage. Whatever the answer, the magic is there. The traveller’s heart will beat to a new rhythm, his ear pick up the tonalities of a new tongue; he will examine the strange new coinage with curiosity. Everything will seem changed, including the air he breathes. L. Durrell, The Greek Islands.)

While he thinks of the shift from Italy to Greece, Durrell reminds us that we are leaving Julius Caesar’s territory and reaching Alexander the Great’s home, two figures who embody the huge differences between these countries that meet in Brindisi, at least virtually. Durrell states:

There is a formidable difference between Rome and Athens, between Italian and Greek; and those with any classical knowledge are astonished to find how constant it is even today. On one side the Italy of finesse and often of finickyness – cherished and tamed by its natives into a formal sweetness. And on the other side Greece, a wild garden with everything running to ruin – violent, vertical and sky-thrusting… undomesticated. One thinks of Roman Italy for whom Nature was always wife, nurse and muse; whereas for Greece she was something wilder, something terrible and unbroken – mistress and goddess without mercy all in one. And their heroes have been different from time immemorial. The traveler watches a tanker come in and make fast, while with half of his mind he wonders if in modern Greece he will come upon traces of Odysseus, the ancient hero. (It is nearly time to go.) (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands.)

Durrell warns the traveler against matching the mythological and classical imagination with the sites he is going to visit, a particularly dangerous attitude when it comes to the Greek world. We suggest the traveler who is following this itinerary should not make this naive mistake and we embrace Durrell’s warning:

A fondness for mythology and folklore is perhaps a handicap when one visit classical sites. It is unwise to spend too much time contrasting the present with the past, since leads inevitably to dissatisfaction with the present for not being romantic enough. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands.)

The writer is accompanying us with his words also on the ferry which is ready to set sail when the night comes.

The crossing lasts one night and at dawn, when he awakes, the traveler will have nearly arrived. Durrell seems to follow the ship journey with his words, over the nautical miles, and we can see the Greek land before our eyes, as in a short film: Corfu island is hunched up to the right of the vessel and the Albanian mountains seem painted in by the sun as it struggles to rise behind them.

The ferry simply forges straight ahead, apparently going to crash into the range of golden mountains before the islands. Gradually we can make out the main channel and the Old Venetian Fortress with its ramparts on the sea.

Now the ship turns abruptly and heads south, leaving Albania on its left. The view is dominated by a big domed mountain called Pantokrator: the traveler who decides to climb to the top may stare out upon the two seas, the Adriatic and the Ionian Seas, on which Corfu and the near islets stand.

In the writer’s eyes, there is an immediate connection between the dawn that tinges both the sea and the islands with its soft light and the Homeric description of Eos, the rosy-fingered goddess of the dawn, who precedes the morning and Apollo’s arrival on her chariot.

As he docks, the traveler cannot help admiring the beauty of the town. “È avvertito – as Durrell explains – non ne troverà di più carine in Grecia e col passare del tempo ciò diventerà sempre più evidente”.

In Corfu, the arrival of ferries coming from Brindisi usually takes place early in the morning, when the elegant old town cafés are already open and ready to serve breakfast, the first breakfast of our itinerary with the poet, who writes:

The old town is set down gracefully upon the wide tree-lined esplanade, whose arcades are of French provenance and were intended (they do) to echo the Rue de Rivoli.

The best cafés are here and the friendliest waiters in all Christendom. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

The traveler is now along the Liston, the long colonnaded street built by the French to imitate Rue de Rivoli in Paris upon the wide and lush Esplanade. In this square, people could once watch the unexpected show of cricket matches, one of the most popular sports in Corfu, still practised, which was introduced on the island by the English. Durrell explains:

There is no place in the world where English are more enjoyed and admired than on the island of Prospero.

As for what they left behind, the cricket comes upon one as rather a shock – the noble sweep of the main Esplanade with its all tall calm trees is suddenly transformed into an English cricket field […].

Under the charmed and astonished eye of the visitor a marquee is run up and two teams dressed in white take possession of the ground. […]

What is singular is the deep and pensive appreciation of the game in an audience very largely consisting of Greek peasants who have never had the chance to play it. They have presumably come in to town to shop from some nearby village, and now here they are, apparently deeply engrossed in this foreign game while their fidgeting mules are tied to trees on Esplanade.

(L. Durrell, The Greek Islands.)

Let’s leave the Esplanade and have a long walk across the narrow old town streets, which open just behind this elegant square. The writer may guide us in discovering them:

The tall, spare Venetian houses with their eloquent mouldings have been left unpainted for centuries, so it seems. Ancient coats of paint and whitewash have been blotched and blurred by successive winters, until now the overall result is a glorious wash-drawing thrown down upon a wet paper – everything running and fusing and exploding. But more precise, though just as eloquent, are the streets between the houses, each a deep gully made brilliant with washing hung out to dry from every balcony – bright as bunting. The great spread of colour moves and sways in the light dawn breeze in a way that reminds one of tropical seaweed. The red dome of the Church of St Spridion shines aloft with its scarred old clock face; the church which houses the mummy of the island’s patron saint. If he knows what is good for him, the traveller will make an indispensable pilgrimage to this dark fane, whose barbaric oriental decoration smoulders among the shadows like the glintings of a fire opal. He will kiss the sacred slipper or a suitable icon and light a candle to place in the tall sconce as he utters a prayer – the subject of which he will confide to nobody. In this way his journey will be under good auspices and the whole of Byzantine, modern and ancient Greece will be waiting with open arms. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

(author: Lao Loong CC BY-SA 1.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/1.0)

Hence, we suggest the traveler visit Saint Spyridon Church, a popular pilgrimage destination all over the Orthodox world. The saint is so important to the Corfiots that he almost identifies with the island. With his irony, Lawrence Durrell dwells on the Saint’s story and the forms of devotion to Spyridon that enliven Corfu life at least four times a year:

What about the history of the island saint? His enormous prestige and influence in the island to this day would justify discussing him here. The relic – and he is a real mummy, a funny little old man like Father Christmas – lies in a chased silver casket in the church of his name which was built in 1589. […] Whoever has seen St Spiridion make a progress round the town is not likely to forget the pomp and magnificence of the strange and baroque procession – the monks and priests like a moving flower-bed with their brilliant gonfalons raised on high. The little figure of the saint lies sideways in his sedan chair, pale and withdrawn, as if in prayer. There are four such processions a year; they take place on Palm Sunday and Easter Saturday, on 11 August and on the first Sunday in November. Naturally the summer appearances benefit from the light – that of August being most sumptuous and colorful.

[…] For a long time Spiridion had not done very much except make routine cures for epilepsy or religious doubts. […] this same old saint had once dispersed fleets, riding upon the afternoon mistral to do so, and even repulsed the plague more than once […] (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

When the traveler comes out of Saint Spyridon Church, whose inner darkness is lit up only by the faithful’s votive lamps and faint candle flames that are reflected in the ceiling and sumptuous liturgical ornament golden stuccoes, he is suddenly enveloped in the warm midday light. It is now that the visitor – our guide points out – may catch the magic of Greek light. He writes as follows:

Coming out of the dark church in to the market he will be almost blinded by the light, for the sun is up; and it is now that impact of this extraordinary phenomenon will begin to intrigue him. The nagging question, ‘In what way does Greece differ from Italy and Spain?’ will answer itself. The light! One hears the word everywhere ‘To Phos’ […].

This confers a sort of brilliant skin of white light on material objects, linking near and far, and bathing simple objects in a sort of celestial glow-worm hue. It is the naked eyeball of God, so to speak, and it blinds one. […].

Each cypress is the only one in existence. Each boat, house, donkey, is prime – a Platonic prototype of a sudden invention;

(L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

Our guide – Lawrence Durrell – warns the traveler that, at the end of his first day in Corfu, he could be tempted to extend his stay, as many other travelers did. In tavernas or cafés you may frequently hear stories of people who came to spend just a pleasant afternoon or some days on the island and then decided to stay and live there. One of these is the writer who is guiding us to discover the island of Odysseus or old Prospero – as other scholars say –, the main character of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

Indeed Corfu, besides being identified, rightly or wrongly, with the Homeric island of the Phaeacians for ages, was also associated with the magic setting of the Shakespearian play. Durrell narrates:

Another, not less speculative, line of mad reasoning has suggested that Corfu is the site which (perhaps by mere hearsay) Shakespeare chose for his last play The Tempest. You may groan as you read this. Is it not enough to have one’s brain criss-crossed and fuddled with the attributes of Greece’s great ace-personality? Must the British shove their alchemical Prospero into the island? […]

One of the magical things in The Tempest is the way the atmosphere of the island is experienced and conveyed by shipwrecked souls when they come ashore. The sleep – the enormous spell of sleep which the land casts upon them. They become dreamers, and somnambulists, a prey to visions and to loves quite outside the ordinary boundaries of their narrow Milanese lives. […]

You will realize that this is exactly what happened to the conquerors who landed here – they fell asleep. The French started to build the Rue de Rivoli but fell asleep before it was finished. The British, who had almost a hundred-year lease on the place, decided that it need a seat of Government and built a most elegant one with imported Malta stone, […]. But they fell asleep and the island slipped from their nerveless fingers into the freedom it had always desired. Freedom to dream. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

The beautiful palace mentioned by Durrell, which the British built as the residence of the Governor is Villa Mon Repos near the old port. Surrounded with a lush garden, among lanes and tree-lined paths, there are the ancient ruins of some shrines dedicated to the Olympians; its interior hosts a museum that exhibits the finds coming from the old area of Paléopolis.

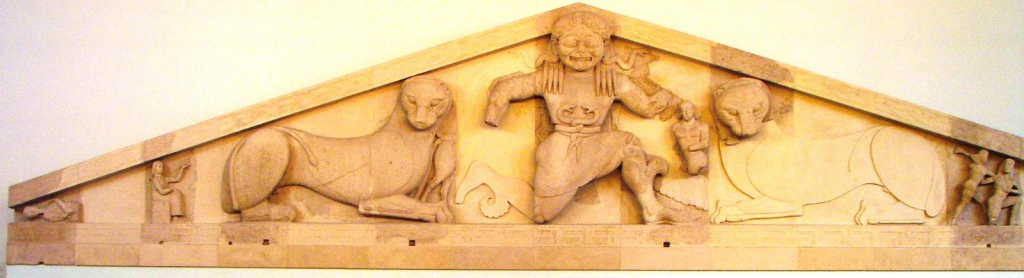

Moving to Via Vraila 1, in the center of Kerkyra, we can reach the Archaeological Museum of Corfu, which remained closed for many years and has been recently reopened to the public. It exhibits the pediment of an archaic temple, probably dedicated to Artemis. This impressive find depicts the terrible image of a Gorgon, almost certainly Medusa.

Durrell tells us the story of this fascinating mythological character:

For she, the mother of the Gorgons, was obviously the warden to the chthonic Greek world just as St Spiridion was the warden of the Byzantine world and the modern. The Medusa, more than life-size, is something which profoundly hushes the mind and heart of the observer who is not insensitive to myth embodied in sculpture. The insane grin, the bulging eyes, the hissing ringlets of snake-like hair, the spatulate tongue stuck out as far as it will go – no wonder she turned men to stone if they dared to gaze on her! She has a strange history, which is not made easier to understand by the fact that several versions of it exist. It is somehow appropriate that in her story we should come upon the name of Perseus, who performed a ritual murder on her, shearing off her head with a scimitar provided by Hermes. It was, in fact, a murder performed with full complicity of the Olympians; the equipment for such a dangerous task (one glance and he would have been marmorealized) consisted of a helmet of invisibility (courtesy of Hades), winged sandals for speed (the Graiae daughters) and a sack for the severed head […]

[…] There are other good things in the little museum but nothing which has such strong vibration; Medusa is indeed the second warden of Corfu, and her existence provides an insight into the nature of the ancient Greek world which one continues to encounter as one journeys among the islands. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

Let’s leave the enigmatic Medusa warding Corfu town off and continue our itinerary in the surrounding villages along the indented coastlines of the island and its uplands.

Moving from the east coast to the west coast, about thirty kilometers from Corfu town, the site of Palaiokastritsa is worth visiting: here, according to one of the Homeric legends, Odysseus met the beautiful Nausicaa.

Several places in Corfu contend for this first encounter, including the evocative Kanoni bay, on the east side.

Neither the beautiful princess nor Alcinous were able to hold the hero on the island, despite enticement and a marriage proposal, hence Odyssesus decided to leave for his homeland Ithaca by the fast ship he received as a gift. Also the traveler, although Corfu beauties invite him to stay longer, should now set off and continue his itinerary in the other Ionian Islands.

Following our guide’s suggestions, by a pair of binoculars we may fully enjoy the sea scenery met when sailing north towards Lefkada. Along this route, we come across the two small islands Paxos and Antipaxos.

Lefkas cliffs (author: almekri01 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The sea the traveler is sailing is rich in stories, and he may have already crossed it with his imagination or reading a school book in the past. Durrell writes:

Even now, standing at the rail, you can turn your eyes on the far lagoons where the Battle of Actium was fought, and see herons flapping about, or the white star of a rising pelican, or the shape of a family of golden eagles moving in slow gyres on the blue. On the other side of you there are two islands of little note – Paxos and Antipaxos. […] The only other interesting piece of history concerning this tiny spot is probably fiction – though it is pleasant to think it might have been true. Antony e Cleopatra are said to have had a dinner party here on the eve of Actium – where so many of their hopes were destroyed. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

This stretch of the Ionian Sea not only is linked to myth and history, but is also a gem of biodiversity where you may admire some rare marine species as the hawksbill turtle and the monk seal. Now it is a rarer event due to pollution, but the writer had the chance to see it.

It is in this channel that I have seen, on more than one occasion, the huge plate-like form of the hawksbill turtle spinning languidly about in the wake of the vessel. It can reach a metre in length, this strange animal, and is astonishingly agile in the water. It is only one variety of sea-creatures which you may be lucky enough to glimpse as the boat furrows its path on down towards the Lefkas Channel […]

One should recall another not infrequent visitor to these caves and quarries among the deserted islands; it was once quite a usual sight, but has now become increasingly rarer. The little monk seal – a brownish mammal (monachus monachus) whose fur is not particularly fine but which has, or had, a delightfully unconstrained manner, presumably because it always found secret coves to breed in and to fish from […]. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

Let’s finally stop over in the “piccola triste isola di Lefkada (o Santa Maura)” as Durrell calls it. The island, which is actually linked to the mainland by means of a raised road, was a real peninsula in the past. Today it is famous for its unspoilt beaches and as one of the hikers’ favourite destinations. The writer warns that “the visitor who really wants to explore it must be prepared for long and stony trudges and longish, bumpy drives”.

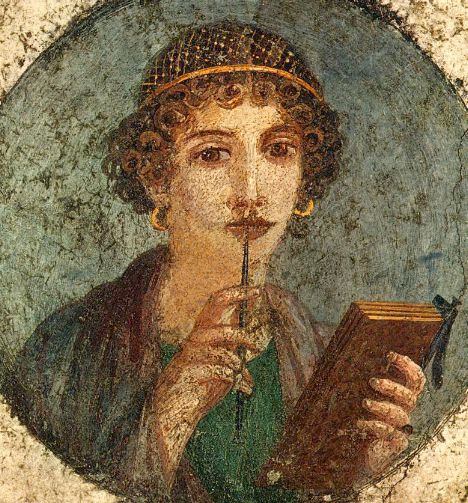

In addition to its natural beauties, in the classical and Romantic imagination, Lefkada is famous for its white cliffs – depicted by painters and poets –, from which the poetess Sappho decided to fall into the sea to end her tormented love for Phaon.

With his British irony, Durrell tells the traveler the story of the unhappy poetess; hence he writes:

Whatever the limitations of Lefkas, it has one feature which commands the attention of the world – the White Cliffs from which the poetess Sappho made her ill-fated leap into eternity. Was it an accident or intent? […] Confused legends suggest that the ancients believed that one could leap straight down into Underworld from here – or at least link up with the River of the Dead, the Acheron. Other traditions say that one could cure oneself of the pangs of disprized love by making the leap, and that this is what Sappho had in mind. […]

As far as Sappho is concerned, it seems that something went wrong. For in the time of Cicero and Strabo the jump was often, and quite safely, accomplished. The priests of Apollo performed it regularly without hurting themselves, and boats were organized to recuperate jumpers. Sometimes plumes and wings were attached to the shoulders of those who chose to leap. The jump itself was called Katapontismos, and one wonders if it did not have some ancient propitiatory function. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

The traveler, if quite physically fit and strong, may follow the path that winds steeply up to Cape Lefkas lighthouse, where a temple of Apollo rose and Sappho’s white cliffs stand. Although they are less typical than the cliffs of Dover, no famous people have never thought of jumping over them and into the English Channel – the British writer recalls.

Our itinerary proceeds towards Ithaca and Cephalonia, as Durell recommends us. Nydri, which was a picturesque fishing village once – today it looks more like a tourist bazaar – is the starting point for boat trips which, before reaching the main islands, stop over on the less known islets of the archipelago that stud the sea journey.

In Ithaca the traveler may discover the most Homeric island of the Ionian group, guided by Durrell’s words. He writes:

Ithaca, which reverberates with the Homeric legend, is a delightfully bare and bony little place, with knobbly hills, covered in holm-oak, which come smoothly down into the sea, into deep water which is rich in fish. […] The entry into Vathy harbour will set the atmosphere for a first visit – it is most remarkable as well as beautiful. The bare stone sinus curves round and round – it is like travelling down the canals of the inner ear of a giant. One is sized with a sense of vertigo. […]

The harbour of Vathy is obviously the old Phorkys, where the Phaeacians deposited Odysseus on his return home […] (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

The traveler who wants to enter the island mythological dimension should make some ‘Homeric’ excursions Durrell suggests: he may search for the real or presumed fountain of Arethusa, and then go into the beautiful grotto of Nymphs, not far from Dexa beach, where Odysseus is said to have hidden the treasures the Phaeacians had given him, or finally reach Mount Aetos. Here, the famous archaeologist Schliemann, who was able to discover the site of Troy holding The Iliad in his hands, claimed to have also found the ruins of Odysseus’ palace.

The writer points out:

The Homeric sites are not all a hundred-per-cent satisfactory from the point of view of identification; but, without being too indulgent or too gullible, one can certainly believe in the fountain of Arethusa […]. One can also combine a bit of home-made piracy with piety and scrabble about in the grotto of Nymphs, in the hope of finding something left over from the treasure Odysseus buried there under the direction of Athena. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

The fountain of Arethusa is a natural spring, about ten kilometers from Vathy, where according to legend Eumaeus, Odysseus’ swineheard, took his pigs to drink and met the hero just landed on the island. However, in Durrell’s view, the most “vexing” problem is to identify the site of the town and the palace of Odysseus. Real or presumed archaeologists are divided on the different hypotheses.

In the northern part of the island, near the small village of Stavros, on Pelikata Hill, among hills covered in olive groves and vines, there are a small archaeological museum and the ruins of a palace with Cyclopean walls. Today, thanks to recent archaeological excavations, it has been identified as the possible palace of Odysseus, which the archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann had previously located near Alalkomenés, close to Mount Aetos.

To the north of Stavros, about a half-hour walk, there are the remains of a sixth-century BC tower, called Homer’s schoolhouse.

Durrell writes ironically:

The less said the better about the site which popular local folklore describes as being the ancient schoolhouse where Homer learned his alphabet…though the view is pleasant enough. This time it is the village folklorists who are being tedious. And yet, so vexing is this whole business that one would not be surprised one day to find out that the obstinate village tradition has a glimpse of truth in it. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

Let’s leave the scholars with their doubts about the Homeric sites and enjoy the view from Ithaca gentle hills.

After a last walk in the pretty town of Vathy, unfortunately seriously damaged by the 1953 earthquake, the traveler may get ready for the next stop of the itinerary: Cephalonia.

Among the many beautiful beaches of the island, Myrtos is worth mentioning, a very long and white expanse of sand, located about ten kilometers from the main isthmus of Cephalonia. Only one scenic route that starts from the center of Divarata leads to this heavenly place.

Unfortunately, there is little left of the historic centers of its towns or of the Venetian buildings that once characterized the island. They were destroyed by the 1953 earthquake. Due to this disaster, which regularly strikes the Greek islands, Cephalonia seems to lack a heart, a “centre of gravity” – Lawrence Durrell points out.

Nevertheless, following the writer’s suggestions, we invite the traveler to get to Assos, a picturesque village on the north-east coast of the island, uniquely located close to a cypress hill and a promontory still dominated by a 16th-century Venetian fortress.

Another site that is worth visiting is the Melissani Cave, forgotten over the centuries. According to myth, the Nymph Melissani committed suicide due to her unrequited love for the god Pan. Besides mythology, this cave is particularly evocative, since it hosts a sparkling lagoon.

In Cephalonia, the traveler may make several excursions on the lush inland mountains, dotted with vineyards that produce the fine wine the island is known for.

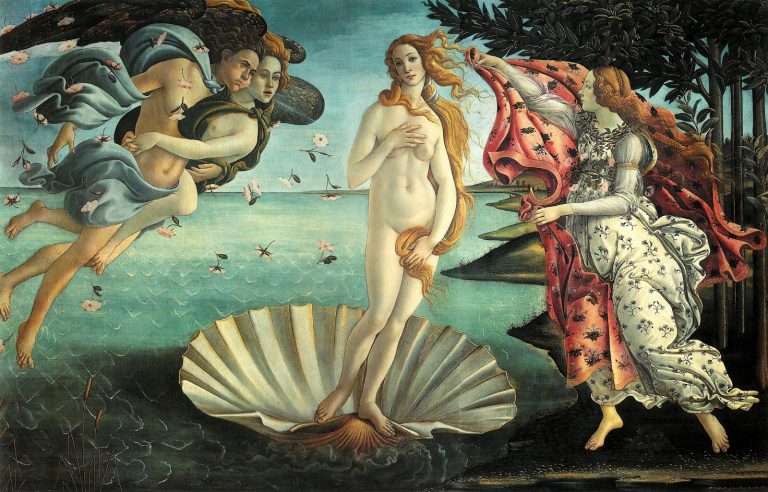

After tasting a glass of Robola, one of the best wines in the area, we may reach the last stop of our itinerary: Zakynthos. The island, described by Ugo Foscolo and Dionysios Solomos, is surrounded by the sea from which Venus, the goddess of beauty and love, was born according to one of the main versions of myth.

Zakynthos offers the traveler an amazing scenery characterized by white cliffs rising straight from crystal-clear waters.

Let’s gain a better understanding of the island, guided by Lawrence Durrell:

Subject to wind and weather, the traveller comes at Zante (Zacynthos), the younger sister of Corfu. Zante, in the past, enjoyed a reputation for even greater natural beauties than Corfu and for the splendours of her Venetian architecture which, despite the frequent earthquake tremors, manage to keep a homogeneousness of style that made the capital one of the most splendid of the smaller towns in the Mediterranean. Only in Italy itself could one find this sort of baroque style, fruit of the seventeenth-and eighteenth-century mind. Then, in 1953, came the definitive earthquake which engulfed the whole of the Venetian past and left the shattered town to struggle to its knees once more. This it has done, in a manner of speaking; but it is like a beautiful woman whose face has been splashed with vitriol. Here and there, an arch, a pendent, a shattered remains of arcade, is all that is left of her renowned beauty. The modern town is… well, a modern town.

Zakynthos town, despite losing its old appearance, of which only fragments and the remains of a Venetian fortress are left, was almost entirely rebuilt in an elegant and vaguely Neoclassical style that gives it a very romantic air.

The patron saint of the island is Saint Dionysios, whose relics are worshipped in the capital’s cathedral. The original church was destroyed during one of the frequent earthquakes that stroke Zakynthos. The new building, erected in the middle of the twentieth century close to the ferry port, has lost its old charm externally, but keeps valuable artworks and various holy icons inside.

Lawrence Durrell narrates that the Saint, in popular devotion, seems to compete with the patron saint of Corfu, Saint Spyridon, on miracles.

He writes:

The patron saint of Zante is St Dionysios – anything Spiridion can do for Corfu, he can do better for Zante. He should be visited and candle-primed with respect – one should not play about with the spring weather in the Ionian. […]. By reputation he occupies himself to the exclusion of other preoccupations with fishermen of the island, and every year he is presented with a pair of new shoes on his feast days. (L. Durrell, The Greek Islands)

After leaving also this Saint, we should say farewell to the traveler come to Zakynthos following the itinerary conceived and written by Lawrence Durrell. The author’s intimate and deep knowledge of these islands that he chose as his homeland for many years clearly emerges from his words. Hence, we would like to share the writer’s hope and imagine the traveler holding a book in his hands – maybe Durrell’s book on the Ionian Islands – years after he returned home:

“Years later, in the pages of a book, the traveller will find a grain sand from this spot, and perhaps a pressed flower or leaf to remind him of something he has never forgotten”.