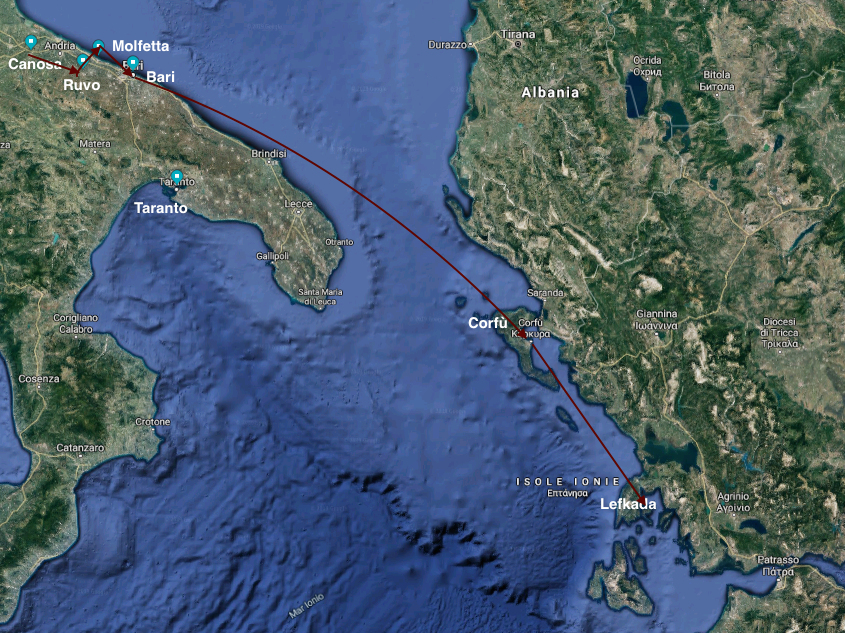

Ruvo, Canosa, Molfetta, Bari, Taranto, Corfu, Lefkada

This itinerary was conceived as a journey across Italy and Greece during the evocative Catholic and Orthodox Easter celebrations. The journey, which develops in Ruvo di Puglia, Canosa, Molfetta, Bari, and Taranto and, in the Ionian Islands – Corfu and Lefkada – will allow the traveler to come into contact with colored processions, Passion plays, culinary customs and old ritual traditions, often between religion, folklore and apotropaic beliefs.

The historian Franco Cardini writes:

La celebrazione della Pasqua è senza dubbio una delle più antiche della liturgia cristiana […]. Probabilmente già dal I secolo i cristiani festeggiavano la Pasqua, che presto dovette essere collegata anche alla prima domenica di plenilunio di primavera […]. (F. Cardini, I giorni del sacro: i riti e le feste del calendario dall’antichità a oggi.)

The Catholic church inherited rituals and ceremonies belonging to preexistent religions and had to enrich salvation symbolism, embodied by Christ’s resurrection, with further meanings, typical of rural and pastoral Mediterranean civilizations. In fact, Easter represents also the spring celebration of plants and fields that come back to life after winter.

In the week before Easter, Puglia turns into a big stage where the episodes of Christ’s death and resurrection are performed live as Sacre Rappresentazioni[1] or processions. In almost every town, confraternities, cultural associations or Pro Loco (local tourist offices) organize events, parades, and music shows that mark the dates of Easter liturgy and the end of winter. A clarification is thus necessary: the traveler who will choose to follow this itinerary may not cover all the stages since the dates of the different events overlap. However, he/she may select the events to be attended in person or ‘virtually’, following their slow pace through the works of the literary guides chosen in the proposed journey.

In the Christian liturgical tradition, precisely emulated by the popular one, Easter time is connoted by great festivals and processions that culminate in the Holy Week, but start during Lent, namely forty days before Easter. The anthropologist and art historian Emanuela Angiuli explains:

La liturgia cattolica fa iniziare il ciclo con il mercoledì delle ceneri, primo giorno di quaresima. In molte località [della Puglia], ancora oggi, la quaresima – periodo di preparazione della morte e resurrezione di Cristo, caratterizzato da divieti alimentari e sessuali, giacché non si consuma carne, non si contraggono fidanzamenti né matrimoni – è rappresentato dalla Quarantana, un pupazzo fatto di pezze nere, il petto trafitto da penne di gallina, appeso ai crocicchi, dondolante come uno spettro. (E. Angiuli, La Pasqua, in Viaggio in Provincia)

1. T. N.: Italian theatrical forms that deal with religious episodes.

One of the places mentioned by the writer is Ruvo di Puglia: a small town in Apulian Murgia, surrounded with vineyards and olive groves, with a thousand-year history linked to agricultural tradition. Here our itinerary may start.

During Lent we can see some puppets hung on the balconies of the Medieval old town alleys: they represent an old lady wearing mourning who is considered the Carnival’s widow. On Eastern Sunday these puppets are burnt using firecrackers. The ritual, called the burst of Quarantane, indicates the end of penance and the victory of life over death, as well as the victory of spring over winter. Emanuela Angiuli narrates:

Ogni giorno la Quarantana perde una piuma, finché nel giorno della Resurrezione, scoppia, riempita di petardi, buttando per aria altri mille stracci neri. Uscita dalla fantasia e dalle feste medievali, la vecchia pupazza incarna l’altra faccia della passione, una sorta di Addolorata alla rovescia, maschera pagana di quell’angoscia di distruzione che l’inverno – interruzione del tempo produttivo, della speranza alimentare – apporta nell’immaginario contadino. […] Le cerimonialità quaresimali, ridotte oggi a processioni di accompagnamento funebre e ad azioni teatrali nelle sacre rappresentazioni, appartengono in realtà ad una concezione festiva apocalittica, propria delle culture agro-pastorali nel mondo mediterraneo pre-cristiano. (E. Angiuli, La Pasqua, in Viaggio in Provincia)

The Holy Week rituals in Ruvo, included within the Italian intangible heritage by IDEA, Istituto centrale per la demoetnoantropologia, do not end with the folkloric burst of Quarantane, but continue throughout Easter, starting on Friday before Palm Sunday.

The procession of the Vergine Desolata is particularly moving; it takes place on Passion Friday[2], namely one week before Good Friday. The statue of the Virgin dressed in black – also called Madonna del Vento since they say a singular breeze always blows during the procession – is carried on the shoulders of the members of the “Purificazione di Maria Santissima Addolorata” Confraternity. The Virgin’s procession starts from the church of San Domenico and ends at the Cathedral.

2. T.N.: It is the term that before the Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican indicated Friday preceding Palm Sunday.

Canosa, women dressed in black who accompany the procession of the Vergine Dolorosa

(Αuthor: Luigi Carlo Capozzi – it:Utente:Campidiomedei – Transferred from it.wikipedia to Commons da Fradeve11 using CommonsHelper., CC BY 1.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4282013)

It has been found that in the Holy Week processions – especially the penitential ones, in which drama prevails on liturgy – the protagonists are female characters as the Vergine Desolata or Addolorata (Our Lady of Sorrows) who grieve over the loss of their child, just like the goddess of fertility Ceres/Demeter mourned her daughter Persephone’s death; this confirms the close link between Easter rites and rural pre-Christian rituals:

Sembra quasi di percepire, nei lunghi percorsi che l’Addolorata attraversa, rappresentata da una statua o da una donna vestita di nero, alla ricerca del Figlio, […] il lamento di Cerere, della grande madre Cibele, menomata all’improvviso, nella mitologia greca e romana, di quella “parte di sé” che rendeva feconda e fertile la terra con l’arrivo della primavera. (E. Angiuli, La Pasqua, in Viaggio in Provincia)

Many of these processions, despite dating back to the Middle Ages, have rituals that directly recall Greek and Roman tradition. For example, the procession of Mater Dolorosa in Canosa is accompanied by the crying of ladies dressed in black that clearly evoke the pagan mourners, women that hurried to grieve for the dead and sing funeral songs during funerals.

Let’s leave Ruvo and Canosa, after visiting the most interesting monuments in these sites, specified in the related links, and head for Molfetta, located on the Adriatic coast in the norther side of Bari, to participate in the Good Friday procession. The intense dramatic force of this show is also enhanced by the singular musical accompaniment provided by the band, one of the features of Apulian folklore events and religious ceremonies.

The Bari musicologist Pierfrancesco Moliterni will introduce us to this melodic world:

All’interno della cultura della festa patronale e della particolare funzione che in essa riveste la banda da giro, caratteristica ed esclusiva è la sua presenza – durante le cerimonie religiose della Quaresima e delle Settimana Santa – nella cittadina di Molfetta. La processione delle statue che simboleggiano la passione di Cristo […] viene preceduta da un particolarissimo “sottogenere” della grande banda da giro: la cosiddetta bassa banda, o banda dei “tammurr” (tamburi). Essa è composta da pochissimi suonatori, di solito in numero di quattro, i quali intonano una specie di trenodia che risuona alla testa della processione, per richiamare l’attenzione dei fedeli all’imminente passaggio cerimoniale.

Il suono di una melodia triste e dolce insieme (flauto) intervallata dal rullo del tamburo militare (cui viene allentata la cordiera d’acciaio per impedire le vibrazioni sulla pelle e sortirne effetti lugubri e cupi) e da colpi profondi di grancassa, viene interrotta da improvvisi squilli di tromba.

La processione vera e propria delle statue oggetto di culto è poi preceduta e seguita dalla banda di Molfetta, che l’accompagna per tutto il tragitto cittadino secondo un preciso cerimoniale musicale, che si tramanda da anni. Le partiture e le singole parti di queste marce funebri del Venerdì santo molfettese sono conservate presso le Arciconfraternite della Morte e di S. Stefano, che ne dispongono solo in occasione delle rispettive processioni-spettacolo. (P. Moliterni, La Processione del Venerdì Santo a Molfetta, in Viaggio in Provincia.)

To attend this event, you should be ready to spend a sleepless night, since traditionally on Thursday night you should visit an odd number of altars of repose – called sepolcri –, set up in the old town churches, have a frugal meal of tuna, capers and anchovies and wait until 3 in the morning when the statues of Misteri (Mysteries), 16th-century Neapolitan school wooden images, leave the church of Santo Stefano and are taken in procession through Molfetta streets.

Following the procession, you may appreciate the old town with its colored port, in whose waters the Cathedral of San Corrado is reflected.

The next stop of this itinerary is Bari, where the most impressive Easter event is the Processione dei Misteri (Procession of the Mysteries) on Good Friday. The beauty of its statues, Neapolitan or Venetian school wooden sculptures or dressed puppets dating back to 17th and 18th centuries, makes it stand out.

The scenic organization of the ceremony is rich and consistent as told by Nicola Cortone, an expert of popular art and local history:

La processione si distingue per le preziose vesti e gli ornamenti, la nobiltà dell’apparato dei portatori (rigorosamente vestiti di nero e guanti bianchi), la melodia delle musiche di bande e i pittoreschi inserti nel corteo di fanciulli e fanciulle, rispettivamente vestiti da guerrieri romani (Costantino) e Sant’Elena, con riferimento al rinvenimento della Croce da parte della imperatrice madre. La presenza di Sant’Elena dona una impronta bizantina alla processione, forse in origine riservata soltanto alla croce.

Gli altri personaggi, via via aggiunti nel corso del tempo, appartengono da un lato al teatro medievale e dall’altro ad una sorta di pellegrinaggio itinerante al Santo Sepolcro.

Attraverso i Misteri in pratica si ripercorrono le stazioni della “Via Crucis” venerate dal pellegrino […]. (N. Cortone, Passione per una settimana, in Bari Vecchia. Percorsi e segni della storia.)

Another distinctive feature connotes Bari procession on Good Friday, making it unique, namely the traditional rivalry between two confraternities that long paraded at the same time, each with its own statues, producing an odd duplication effect as well as causing disputes and brawls over the right of way.

In the 18th century the Processione dei Misteri (Procession of the Mysteries) was organized by the confraternity “Maria Santissima Della Purificazione” and by the Franciscan Reformanti that let their statues exit the church of Vallisa. However, there was a similar procession in town on Good Friday: it started from the church of San Pietro delle Fosse, near the port, and was arranged by Friars Minor Observants. When the religious order was suppressed in 1809, the confraternity’s statues were moved to the church of San Gregorio, belonging to the Basilica di San Nicola. The two processions continued to compete and, when the parades crossed, they caused such disorder that the Archbishop had to intervene and in 1852 established that the Misteri (Mysteries) of Vallisa would have been taken in procession in even years, whereas the Misteri of San Gregorio in odd years. This archbishop’s order is still effective. Cortone writes:

La processione dei Misteri baresi, oltre che storica, diventa pittoresca e polare nella duplicazione della serie delle statue. (appartenenti alle due gloriose confraternite già citate), che dopo un lungo periodo di conflitti e tensioni sull’ordine delle precedenze, attualmente “escono” ad anni alternati dalle rispettive chiese […].

Ad esse è stato affibbiato dal popolino una duplice denominazione di chiangeaminue (“piagnoni”, quelli della Vallisa) e venduluse (“ventosi”, quelli di S. Gregorio), capaci cioè di sollevare vento o scrosci di pioggia in occasione della loro uscita. (N. Cortone, Passione per una settimana, in Bari Vecchia. Percorsi e segni della storia.)

While a sleepless night was required to take part in Molfetta procession, the traveler should be in shape to follow Bari procession, since it is the longest in Puglia, together with the one in Taranto. The statues cover various parts of the city, from the old town to Libertà district, behind the promenade, for fifteen hours.

Many scholars, anthropologists and historians have focused on the Holy Week processions: one of the best known in the region is definitely the «solenne e notturna» procession of the incappucciati (hooded figures) in Taranto, the next stop of the Passion itinerary. We deemed right and proper that a writer from Taranto should be our guide, the young intellectual Alessandro Leogrande, dead prematurely. He devoted a chapter of his report on Taranto, Dalle Macerie. Cronache sul fronte meridionale, to the Processione dei Misteri (Procession of the Mysteries). Hence, his words can lead us to the town alleys while the procession parades.

Leogrande describes it as follows:

Una decina di statue raffiguranti i momenti della Passione dondolano nella notte sorrette da uomini. Sono statue scolpite nel legno secoli addietro, i loro colori sono accesi, i loro volti rotondi, sofferenti. […]

Tra l’una e l’altra ci sono le coppie di Perdoni, cioè coppie di confratelli incappucciati che precedono a piedi scalzi sull’asfalto con la stessa lentezza con cui avanzano i gruppi che sorreggono le statue. Sembrano danzare. Ondeggiano con movimenti appena percettibili, da sinistra a destra, da destra a sinistra, sospingendosi ogni volta di qualche centimetro in avanti. Il verbo preciso è nazzicare, la loro camminata si chiama nazzicata.

In fondo, la banda musicale suona marce funebri che paiono una lunga nenia, mentre ai lati della strada un carnaio umano variamente assortito piange, ride, prega, scatta foto, osserva attentamente, sfiora sensualmente il corteo che si snoda per le strade della città.

È la Processione dei Misteri di Taranto. Esce ogni anno dalla chiesa del Carmine nel primo pomeriggio del Venerdì Santo e vi farà ritorno solo nella tarda mattinata del giorno successivo. Insieme alla processione gemella, quella dell’Addolorata, che esce il giovedì notte dal portone di San Domenico e vi fa ritorno il venerdì all’ora di pranzo, costituisce un pezzo di Sud barocco, sopravvissuto allo scorrere dei secoli e conficcato nella nostra modernità. […]

[…] tra le due Processioni c’è un’enorme differenza: quella dell’Addolorata si snoda tra i vicoli della città vecchia e approda nella città moderna solo per poche centinaia di metri;

mentre quella dei Misteri, benché sia nata nella medesima isola, si è poi spostata interamente nella città nuova.

Se nella prima la coincidenza tra luogo e rito appare perfetta, nella seconda lo stridore è molto forte. Si fa evidente soprattutto nelle prime ore, quando accanto alla Processione dei Misteri c’è la Diretta Televisiva della Processione dei Misteri, e c’è talmente tanta gente in strada che il percorso è transennato. Quando le telecamere si spengono, la gente si dirada e la gran parte dei tarantini va a dormire dopo aver sgranocchiato lupini o panzerotti con la mozzarella e il pomodoro, a “fare” la processione rimangono solo i Perdoni, i loro confratelli, pochi famigliari e qualche fedele con un cero acceso in mano.

[…] Un senso di morte e disperazione sembra salire dalle viscere della città. […] Il passato rimosso della città sgorga fuori all’improvviso, e con esso i suoi fantasmi, le sue inquietudini, la richiesta ancestrale di una grazia o di un miracolo, mentre in lontananza le ciminiere dell’Ilva illuminano la notte e le onde del mare rimescolano l’acqua nel golfo. (A. Leogrande, Dalle Macerie. Cronache dal fronte meridionale)

Taranto, Processione dei Misteri (Procession of the Mysteries), Ecce Homo

These events, which attract the crowds to Apulian town for days, are not free from contradictions: the original religious and educational value on which the shows – demanded by the post-Tridentine ecclesiastical hierarchy – were grounded, has now reduced. While some believers consider Easter processions as a key moment in their religious sensibility, many people now perceive them as a custom event, an opportunity to eat typical food or merely to attend a show neglecting its deep meaning. The anthropologist Emanuela Angiuli writes:

I visi delle statue scomposti dal dolore, i tratti disperati delle Vergini Desolate, la vivezza delle carni piegate ed illividite delle figure del Cristo, non sono semplici prodotti di abilità artistiche, ma referenti puntuali, segni di un’apocalisse precipita nella storia culturalmente controllata, nella quale gli “umili” entrano ed escono indossando gli abiti della penitenza, con la testa coperta di spine, le spalle schiacciate dal peso delle croci, in una sequenza di quadri in cui i protagonisti vivono la morte della propria condizione di sfruttati e subalterni. (E. Angiuli, La Pasqua, in Viaggio in provincia)

The discordant ambiguity of these events highlighted by Alessandro Leogrande in the Processione dei Misteri description takes a more dramatic tone in another book he wrote, published in 2011, Il Naufragio, which is about the tragedy of the ship Kater i Rades, full of migrants, that sank in the Strait of Otranto just on Good Friday night, a deadly Friday, while the Procession of the Mysteries paraded in Taranto:

La folla segue la processione dei Misteri, […]. Stipato tra la folla il Capitano Fusco si ritrova a fissare la statua chiamata “Ecce Homo”: un Cristo triste con la corona di spine posta sulla testa insanguinata e una pezza rossa intorno al corpo nudo. Osserva i suoi occhi. Guardano verso il basso. Più che di dolore sono carichi di stupore. Quell’uomo, scolpito nel legno tre o quattro secoli prima, non sta provando compassione per il mondo, ma stupore. Una profonda meraviglia, velata di tristezza, per la violenza, il non senso, l’indifferenza, l’ignavia, l’impossibilità di raddrizzare le cose. Quel Cristo dai lineamenti popolari sembra un innocente piombato improvvisamente in mezzo a una mattanza. Lo dicono i suoi occhi. Pensa e ripensa questa idea che gli è balenata in testa: un agnello in mezzo alla mattanza. Ma poi si distrae, è infastidito dai flash, dalle urla, dalle risate di un uomo grasso con in mano un pezzo di focaccia al pomodoro che gronda olio da tutte le parti.

Questa processione non ha niente di religioso, pensa. È tutto fuorché un evento religioso. È fatta di urla, non di silenzio. Di sovraesposizione, non di riflessione. Così si allontana e si dirige verso la macchina… (A. Leogrande, Il Naufragio)

Let’s leave Puglia, with its processions and rituals and continue the Passion Itinerary in Greece, in the Ionian Islands, to take part in the celebration of Orthodox Easter. If the traveler is lucky, the dates will not overlap. In fact, the Orthodox kalendar is different from the Catholic one. Hence, Easter is celebrated in Greece after the Latin festivities. Determining the date of Easter day was one of the main worries for Early Middle Ages ecclesiastical intellectuals, considering that complex secular calendars, called tabulae paschales, were elaborated in order to facilitate the determination of Easter day.

The difference between the Catholic and Orthodox dates lies in the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in the West, whereas in the Orthodox context the Julian calendar remained effective.

Easter is definitely the most important feast day of the year in Greek religion, in which Byzantine mysticism combines with purely insular folklore. In particular, Corfu island is famous for the events that enliven every village, making this period of the year one of the best moments for the town secret discovery, provided that you like confusion.

The great Sicilian writer and anthropologist, Giuseppe Pitrè, one of the leading folklore experts, has devoted a paragraph of his monumental book Archivio per lo studio delle tradizioni popolari, published in 1899, to Corfu Easter. The paragraph title is Usi pasquali nell’isola di Corfù, and the feast is described as follows:

La più graziosa delle città elleniche è senza dubbio Corfù. Tra gli usi pasquali tuttora in vigore i più caratteristici sono i seguenti: al momento di sciogliere le campane il Sabato Santo, si gettano dalle finestre gli utensili rotti conservati in casa durante l’anno, cosicché per qualche minuto è pericoloso trovarsi fuori di casa. Vetri, stoviglie volano per l’aria e con fracasso ingombrano il suolo. Quei buoni isolani dicono di cacciare tutta quella robaccia poco gradita dietro a Giuda in segno di disprezzo.

Altra usanza è quella degli spari. Questa dura dal mezzogiorno del Sabato Santo a quello della Domenica di Pasqua. È un bombardamento non interrotto.

Rivoltelle, vecchi fucili e pistole, mortai, tutto viene posto in opera.

Caratteristica quanto mai la processione nel Castello alla mezzanotte del Sabato Santo. La ricchezza degli apparati, l’intervento della truppa e delle autorità, l’ora e le fiaccolate multicolori, danno alla funzione un’aria affatto speciale. Tipica e commovente pei sensi che nasconde la veglia che si fa con l’agnellino la notte del Sabato santo. Al mattino della Domenica di Pasqua ogni casa sgozza sul limitare il suo agnellino. Il sangue scorre per le vie, e col sangue stesso ancora caldo si disegnano croci sugli usci e sulle pareti. (G. Pitrè, Archivio per lo studio delle tradizioni popolari.)

Corfu, Saint Spyridon procession on Palm Sunday

During our stop in Corfu we may discover what has changed and how enduring certain traditions are, more than one century after the Sicilian writer’s study.

The ritual celebrations start on Saturday preceding Palm Sunday. This day is celebrated in memory of the miracle that restored Lazarus of Bethany to life, with traditional songs performed by choirs coming from all island’s villages. The girls, wearing traditional clothes, go round the houses and chant songs called kalanda of Lazarus. On this occasion, people eat typical biscuits called koulorakia or Lazzarakia, since their shape recalls that of Lazarus’ body wrapped up in the shroud.

On Palm Sunday, in a town decorated in red, as purple cloths are hung on every balcony, the relics of the patron saint, Saint Spyridon, are taken in procession, followed by a joyful crowd of believers and the eighteen Philharmonic Orchestras of the island. This habit has recurred every year since 1629 when, according to hagiographic legend, Agios Spyridon freed the island from the terrible plague. Besides being an extremely fascinating event, which ends with music concerts in the old town, it is also one of the only four circumstances in which it is possible to see the saint’s relics through Corfu alleys. The English writer Lawrence Durrell, genuinely fond of the island, where he lived for several years, wrote that Saint Spyridon and Corfu nearly identify with each other, since they are closely linked: “The island is really the Saint: and the Saint is the island”. The writer describes this procession as follows:

The saint lies quite composed in his casket. He is a mummy, a small dried-up anatomy, whose tiny feet (clad in embroidered slippers) protrude from a vent at the bottom of his sarcophagus. […]

Four times a year is the Saint’s casket borne on triumphal procession round the town; while on Christmas Eve and at Easter he is placed on a throne in the church and accessible to all comers. But the processions are something more than empty form. From early morning the streets are crowded with the gay scarves and headchiefs of peasants from outlying districts who have come in to attend the service; every square is alive with hucksters’ stalls selling nuts, ginger-beer, sweetmeats, carpet-strips, buttons, lemonade, penholders, bootlaces, toothpicks, lucky charms, ikons, wood carving, candles, soap and religious objects.[…].

The procession is led by the religious novices clad in blue cassocks and carrying gilt Venetian lanterns on long poles; they are followed by banners, heavy and tasselled, and rows of candles crowned with gold and trailing streamers. The huge pieces of wax are carried in a leather baldric – slung, as it were, at the hip. After them comes the town band – or rather the two municipal bands, bellowing and blasting, with brave brass helmets of a fire-brigade pattern, glittering with white plumes. Now troops in open order follow, backed by the first rows of priest in their stove pipe hats, each wearing a robe of unique colour and design – brocade of roses, maize, corn. grass-green, kingcup-yellow. It is like a flower bed moving. At last the archbishop appears in all is pomp, and since he is the signal for the Saint to appear, all hands begin to make the sign of the cross and all lips lo move in prayer. The Saint is borne by six sailors under an old canopy of crimson and gold, supported by six silver poles and flanked by six priests. He is carried in a sort of sedan-chair, and through the screen his face appears to be more than ever remote, determined, and misanthropic. (L. Durrell, Propero’s Cell. A guide to the landscape and manners of the island of Corfu)

As in Italy, the most heartfelt day in the Holy Week is Friday, the Passion day, also called Epitaph Friday, namely the day of Sepolcri. All over the island, every church takes its own Epitaph in procession, in a flower-adorned canopy. The faithful follow their parish Epitaph emulating the rhythm of the sad funeral marches played by music bands.

On the following day, Holy Saturday, the earthquake after Jesus’ death – as told in the Gospels – is performed in the church of Kyra Panagia Faneromeni, in Agiou Spyridonos square, on early morning; the faithful beat the pews creating such a noise that the church seems to shake.

Later, the patron saint – Spyridon – parades through Corfu streets again with his sepulcher, in memory of the ban imposed by the Venetians on taking Epitaphs in procession on Good Friday.

The most colorful and typical time of Orthodox Easter in the island is 11 in the morning, namely the start of the show in which botides are smashed.

Big terracotta vases, painted red, are thrown in the street from the old town balconies, and smash into a thousand pieces. The origin of this custom, linked by Giuseppe Pitrè to the popular will to drive Jude away, according to other scholars recalls the Venetian tradition of throwing old objects from the windows at New Year.

At late night, just before midnight, the Resurrection is finally celebrated and the island sky is lit up with fireworks. The faithful sing joyful songs, following the music played by philharmonic bands, and wish each other a Happy Easter using the traditional formula Χριστός ανέστη (Jesus has risen).

In the villages the custom of sacrificing the Easter lamb and marking the house doors with its blood is still alive. This tradition probably recalls the period when, as Franco Cardini writes, “in un ormai lontano plenilunio di primavera, […] il sangue dell’agnello sacrificato protesse le case degli Ebrei dal passaggio dell’Angelo”. The Book of Exodus narrates that, before Israelites’ deliverance from slavery in Egypt, an angel sent by God would have hit every Egyptian firstborn and saved Israelites, who marked their doors with the blood of a sacrificed lamb, as ordered by Moses complying with God’s will: “[…] quand’io vedrò il sangue, passerò oltre, e non vi sarà piaga su di voi per distruggervi, quando colpirò il paese d’Egitto”. The lamb, a victim in the Exodus and king in the Apocalypse, is still one of the most powerful Catholic and Orthodox symbols of Easter. Resurrection Sunday is the day of food, when Corfu people, after Lent fast, enjoy rich meals of lamb and goat meat.

If Easter festivities take solemn and spectacular tones in Corfu, in the other Ionian Islands the traveler may have a more intimate and less social experience. Hence, we have chosen Lefkada as the last stop of our itinerary. With its white cliffs, famous for the poet Sappho’s suicide on account of her love, the island, which is still outside mass tourism routes, is a place where life has a slow and natural pace and Easter is the most important event of the year. The rituals take place all over the Holy Week, when the villages are adorned, the houses are painted white and the streets are cleaned. Godfathers and godmothers give their godchildren new and white clothes, along with an Easter candle. On Holy Thursday women paint the eggs red and on Good Friday the parade of Epitaphs takes place. On Saturday at midnight the faithful’s candles are lit up and a cross is drawn on the house doors by their smoke, while the bells ring and the fireworks explode in the sky with their colors. On Sunday the Agàpi ceremony takes place: the Greek word refers either to love in its divine and Platonic dimension or to holy libations. In fact, after reading the Gospel in twelve different languages, an extremely rich meal of roasted lamb meat and honey cakes is enjoyed.

The traveler who has taken this itinerary may symbolically join the Easter banquet. After going through the Passion days, with dramatic ritual processions, Sacre Rappresentazioni, and litanies, time for joy and rebirth as well as our time for return has come. Our itinerary, which ends here, has led us to visit wonderful places and also to discover old Mediterranean traditions related to our religion Gospel events and to man’s nature: over millennia men, with their own contradictions, have turned their fears and sufferings into rites and celebrated their divinities and great nature’s cycles.