Canosa, Ruvo, Bari, Egnazia, Gravina, Altamura, Taranto, Corfù, Lefkada, Itaca

The Itinerary of myths and heroes is a journey that will guide the traveler or reader through the archaeological areas of Puglia, along the Appian Way and its deviationes, between mythological tale and history, following the historical writings of famous authors from the past such as Orazio as well as prestigious contemporary writers like Paolo Rumiz; these travellers have crossed and described this Way. The main stops will be Canosa, Ruvo, Bari, Egnazia, Gravina, Altamura and finally Taranto, one of the most important centres of Magna Graecia, which boasts one of the most beautiful archaeological museums in the world: Marta. Following this itinerary, the traveler will finally be invited to cross the Adriatic to reach the Ionian Islands, which enjoy a unique position in the mythical and epic Western imaginary. The Homeric poems, which are set in this fascinating and fantastic insular world, have over time led people to overlap the literary image of the island of the Phaeacians with the real image of Corfu, and to consider Ithaca as the home of the most famous traveler of all times: Ulysses. Entire generations have been fascinated by a journey that perhaps never took place; although the historical-archaeological evidences are very few and do not allow for a sure identification of the Ionian Islands as the actual theatre of the peregrinations described in the Odyssey, «il turista che, appressandosi per mare alla Grecia, oggi vede da lontano Itaca – as Umberto Eco notes – prova un’emozione omerica». The travellers who are interested in following this itinerary will be invited to go in search of those Homeric emotions by following these islands with the Odyssey in their hands and guided by an educated eighteenth-century writer and traveler, Saverio Scrofani, who has left us intense descriptions of these places, full with mythological and classical suggestions in his book Viaggio in Grecia.

Our itinerary begins in Puglia with the poet Orazio, who in 37 BC at the age of 28, together with Maecenas, Cocceius and Virgil, travelled from Rome to Brindisi. Years later, the memory of that experience became the theme of the fifth satire of the first book from Saturae by the Latin poet. Known as Iter Brundisinum, we advise the traveler to follow the route. Horace and his traveling companions reach Puglia from Benevento and instead of following the main road of ancient Appia, also referred to as regina viarum, choose a way that was still secondary at the time. As time went by, this alternative route became one of the most important routes in the South: the Appian Trajan Way, the route axis built between 108 and 110 AD at the behest of Roman emperor Trajan.

Our first Apulian stop is Canosa which, in Horace’s words, is a city where bread is harder than stone and “che è stata fondata un tempo dal valoroso Diomede”. (“Qui locus a forti Diomede est conditus olim“). The image of the Achaean hero is linked to the birth of many Apulian centres. Legend has it that upon returning from the Trojan War he landed on these shores and founded numerous cities, including Canosa. The relations between Puglia and the Greek civilisation are very ancient, as evidenced by the foundations of numerous settlements linked to the Minoan, Mycenaean and Achaean universe as early as the second millennium BC. This contributed to the dissemination of legendary and mythological stories in various ways linked to the heroes of the Trojan war. Among all, Diomedes is one of the most beloved characters, the protagonist of romantic legends. The hero, who is Ulysses’ companion, after escaping from a conspiracy orchestrated by his wife at the behest of Aphrodite, landed in Daunia and chose this land, which the gods wanted him to call ‘Terra Felice’, to found several cities. The borders were traced with gigantic stones that Diomedes had brought with him from Thrace and threw the three remaining ones into the sea. These became as many islets, i.e. the Diomede Islands, today known as the Tremiti Islands. It is not only the myth and legend of its foundation that testifies to the antiquity of Canosa, but also the numerous archaeological finds that emerged from the subsoil and some of its most beautiful monuments. Just twenty minutes from the centre in the Archaeological Park of San Leucio, the traveller can visit the remains of a Paleo-christian Basilica immersed in a verdant countryside of olive trees and vines, which are built on an already-existing Italic temple from the third century BC; according to scholars, this was dedicated to goddess Minerva. Among tall columns in white marble surmounted by Ionic capitals and Byzantine pulvinos, polychrome mosaic fragments of fine workmanship are still visible. In the ancient temple you can admire the Corinthian capital, which is of rare beauty, with a female protome, the drums of numerous fluted columns and the feet of a gigantic telamon.

After visiting the annexed Antiquarium, we continue our itinerary towards Ruvo di Puglia. Upon arrival, his illustrious travelling companions are “stanchi, come chi ha percorso un lungo tratto e reso più difficile dalla pioggia”.

From an exceptional artistic point of view and despite some nineteenth-century repainting, the vase presents in the foreground the figure of the mortally-wounded giant, who collapsed supported by the Dioscuri. The god of the sea Poseidon and his companion Amphitrite witness the scene, while a female figure, a personification of Crete, flees scared of losing the protection of her guardian.

In Ruvo, the ancient Rubi, an important stopping point along the Appian Trajan Way, ancient history and myth – the two cornerstones of this itinerary – once again meet. The town is an important agricultural centre of the Apulian Murgia and its origins date back to the time of the Peucetians, an ancient Italic population which had already settled in these lands as early as the seventh century BC. It was a Roman municipality and its importance is linked to its strategic position along the route that connected the inland areas of the region with the port cities of the Adriatic coast. Getting here following Horace’s journey, the traveller cannot leave Ruvo without first visiting the Jatta Museum, not only for the rich heritage of Apulian vases that it hosts, but also for the museographic framework in which they are exhibited: the neo-classical Jatta Palace. The Museum is one of the very few examples of a private collection in Italy, formed between 1820 and 1935, which remained intact and set up according to the late nineteenth-century taste. It contains a valuable collection of over 2000 vases found in the Ruvo area thanks to the commitment and the passionate archaeological research carried out by Giovanni Jatta and his family. The Jattas wanted to put an end to the nineteenth-century widespread practice of plundering ancient tombs and burial grounds for commercial and speculative purposes; for this reason, they began to purchase artefacts on the antiques market and to preside over excavation campaigns, thus saving a large part of the historical and archaeological heritage from grave robbers and smugglers. The precious family collection constitutes the Jatta Museum Collection. One of the museum’s most valuable pieces is found in Room 4: it is an Attic crater that probably dates back to the fifth century BC; it represents a scene from the Argonautics by Apollonio Rodio, the Death of Talos. Here the myth reappears. Talos was a giant demon, the keeper of Crete, who was killed by the Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, with the help of Medea, in order for Jason to land on the island after conquering the golden fleece.

We leave Ruvo, its myths and its archaeological treasures, to continue our journey along the Appian-Trajan way to reach Bari, briefly defined by Horace as a “fishy” city.

The traveller who arrives today in the Apulian capital is more likely to be captured by the medieval aspect of the city, which instead preserves its archaeological treasures in the recently restored Archaeological Museum of Santa Scolastica, on the Lungomare Imperatore Augusto; this runs under the ancient city wall. Here the remains of ancient Roman columns are still aligned, probably belonging to buildings that have disappeared today. Among these, the traveller will come across one of the milestone columns of the Trajan Way, found in the immediate vicinity. The dedicatory inscription in honour of the emperor Trajan and the indication of the CXXVIII (128) mile distance from Bari and Benevento are still visible on it.

In the heart of the alleys of the historical centre, among which we recommend visiting the Cathedral of San Sabino and the Basilica of San Nicola, the traveller will be able to take a suggestive journey back in time, visiting the exhibitions set up in Palazzo Simi – Operative Centre for Archeology -, in Via Lamberti 1. Inside this Renaissance mansion you can appreciate both vertically and horizontally a dense archaeological stratification that shows the long history of Bari and its pre-existing archaeological features characterising the subsoil through its finds, tools and ceramic artefacts.

From Bari, our itinerary to discover the archaeological heritage and the mythological stories of the Apulian cities and towns leads us near Monopoli, on the Adriatic coast, where there are the remains of an ancient settlement dating back to the Bronze Age: Egnazia.

The Latin poet, after arriving in what had already become a thriving Roman city, quips about local legends and writes:

Egnazia, costruita in ira alle Ninfe, ci offrì motivi di risa e di scherzi, giacché desiderava convincerci che l’incenso sulla soglia del tempio si consuma senza fiamma. Ci creda Apella il giudeo, non io: io infatti ho imparato che gli dei conducono vita tranquilla e, se qualche prodigio la natura produce, non sono gli dei irati a mandarlo giù dall’alto tetto del cielo. (Orazio, Satire, I, V)

Egnazia, the ancient Gnathia of Messapi, still preserves the remains of its ancient walls, which also attracted the attention of another illustrious traveller, like us, in search of the ancient: Baron Von Riedesel, a correspondent of the famous archaeologist Winckelmann from the late eighteenth century, to whom he described the site with the following words,

[…] si veggono, ancora, le sue antiche mura, che si elevano di qualche palmo dal suolo, e son di pietra da taglio, posto a crudo, ossia senza calce e cemento; inoltre, una tomba antica, una conserva di acqua sotterranea, che può aver servito a dei bagni, e che si riconosce essere stata decorata di stucco; ed infine, un altro edificio sotterraneo, di forma quadrata, con un’apertura in ogni angolo, probabilmente, per dargli luce ed aria. Io lo credo, del pari, una conserva d’acqua, essendo necessarii simili edificii in un paese di pianura come questo, nel quale mancano buone sorgenti, e nel quale bisogna ricorrere all’acqua piovana. (H. Von Riedesel, Viaggio attraverso la Sicilia e la Magna Grecia)

Still today the traveler will be able to appreciate the ruins of Egnazia, once an important Roman civitas foederata, then municipium, located along the Trajan Way, within its scenic position in front of the sea. The Roman city experienced its maximum development at the turn of the second and third centuries AD.

The paved route axis of the imperial way is still perfectly legible; to its sides one could find the shops, the forum, the civil basilicas and a vast sanctuary from the Augustan period.

The area has been the subject of numerous study campaigns and archaeological excavations and, since 2016, numerous paths have been opened to the public, allowing tourists to visit the city supported by modern multimedia technologies. The finds from the excavations of Egnazia are now preserved in the nearby Giuseppe Andreassi National Museum.

After this archaeological walk and if the season allows for it, the traveler could take a dip in the clear waters of the Adriatic which sometimes dangerously touch the archaeological area “Invisa alle Ninfe”. Many equipped bathing establishments follow each other along this stretch of coast.

At this point in our itinerary, we leave the poet and his group to proceed towards Brindisi, while we will divert our journey towards the inland areas of the region to reach Taranto, reconnecting to the original route of the Appian Way.

If Horace can be considered as one of the most illustrious travellers of Puglia among the ancient writers, in much more recent times, in 2015, another famous writer and well-known journalist, Paolo Rumiz, ideally picked up the baton. Together with a group of friends, he travelled along the ancient Appian Way from Rome to Brindisi, partly following the course of Horace’s iter brundisinum, unlike the poet, who remained faithful to the oldest route layout. The story of this incredible journey has become a book, entitled Appia, which, by welcoming the wishes of its writer, we have chosen to use as a guide during the last Apulian stages of this journey on the routes of myths and heroes.

The journey that we propose to the traveler is the one that from Gravina leads to Taranto, retracing exactly the route of one of the most important paths of antiquity, one that can aspire to become the Italian Way of Santiago and that Rumiz «come un pifferaio magico» invites us to follow both physically and with our imagination.

The writer arrives in Puglia after crossing Lazio and Campania, from the border with Basilicata, and writes the following:

Dalla Basilicata alla Puglia un lungo andare nel silenzio, fra panorami e infinite e nude distese a seminativo. […] Scampoli di tratturo Tarantino-Appia Antica conducono su e giù verso Gravina, gioiello che prende il nome dal canyon inserito nel Parco nazionale dell’Alta Murgia. Sul lato del burrone opposto a quello dell’attuale città, nel sito di Botromagno, che fu colonizzato dai Peuceti, i Romani avrebbero costruito la stazione di Silvum. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

We advise the traveler to stop in this town, which is built on the slopes of a deep ravine, with unique landscape features, to discover the many crypts, rupestrian churches and its monuments.

We leave the task of describing this evocative place to Paolo Rumiz:

Sull’orlo del precipizio che le dà il nome, Gravina emerge in fondo a una lunga spianata stepposa tipo Arizona. Il contrasto fra la luce calcinata della città e l’ombra smisurata del burrone è impressionante. […] Ma quello che fa la vera differenza è che Gravina è una città in negativo: scavata nella pancia del tufo più che costruita attraverso muri maestri. […]

Il solido tufo di Gravina fa sì che il segno dell’Appia si perda in un labirinto di tracce di carriaggi e antichi marciapiedi. […]

Sulle mappe antiche il nome attuale della città non esiste. Al suo posto, nell’itinerario dell’Appia è segnata Sylvium. Ma Gravina, secondo alcuni, non ha nulla a che fare con questa. E allora Sylvium dov’è? (P. Rumiz, Appia)

To answer this question, our journalist and traveler interpellates the archeology experts who reveal that today’s town is very likely to be the neighbour of Sylvium, heir to a Greek centre called Sidinon, a term that derives from the Greek word «Side» which means pomegranate. On some coins, which were found in the hill west to the deep ravine that cuts the town in two, this toponym can be read. In this case, it is better to head towards this hill called Botromagno with Rumiz. Although the archaeological area has remained fortunately intact, as the medieval and modern town of Gravina has developed on the opposite side of the ravine, the site is difficult to reach and visit.

“Gravina – as Rumiz states – è una città verticale, un condominio rupestre con le case dei ricchi in alto e quelle dei poveri in basso. Ma ecco che proprio questa città termitaio ha la particolarità unica di avere le sue stratificazioni storiche in orizzontale. Una di fronte all’altra, anziché una sopra l’altra, come normalmente succede”. He then goes on:

Botromagno, oltre la gola, sembra impersonare il “doppio” sepolcrale della città dei vivi. “Botros” per i Greci era nient’altro che il canyon, per cui il toponimo – per dirla con il Signore degli Anelli – può essere efficacemente tradotto con “Gran Burrone”. Ma “burrone” è esattamente come dire “gravina”, parola antichissima derivante dall’accadico “Grab” – fossa, tomba –, tuttora usata nel tedesco, ma con in più una connotazione sacra legata alle acque. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

The traveller visiting Gravina cannot help but notice that the surrounding area is characterised by a vaguely sepulchral aura, conferred by the numerous caves used as necropolis and the ancient burial grounds along the sides of the ravine. Moreover, if he is lucky, he may come across some villager ready to tell him the stories and legends that populate these rocks. Paolo Rumiz met Pino who told him how the village elders believed that ancient demons still lived in that place. Rumiz writes:

Quando passo lì accanto la sera, sento voci, vedo fiaccole alle finestre, dice Pino, ricordando che Gravina è luogo di abitazione e di culto da tempo immemorabile. Mio nonno disse che una notte aveva udito urla umane e un rombo di carri e cavalli al galoppo. Era corso dal parroco a raccontare la visione e quello gli aveva dato alcune effigi benedette per proteggersi dai demoni. Ebbene pochi giorni dopo, proprio in quel luogo, furono trovate due tombe greche, e nessuno tolse dalla testa al nonno l’idea che le grida fossero uscite da quella finestra sull’Ade. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

We leave Gravina, its caves and its stories, to continue our itinerary along the Appian Way on the steps of Rumiz who, after crossing the Murgia, passes through Altamura, according to some scholars the ancient city of Blera, the next stop within our journey. The journalist describes his difficulties walking this stretch of road:

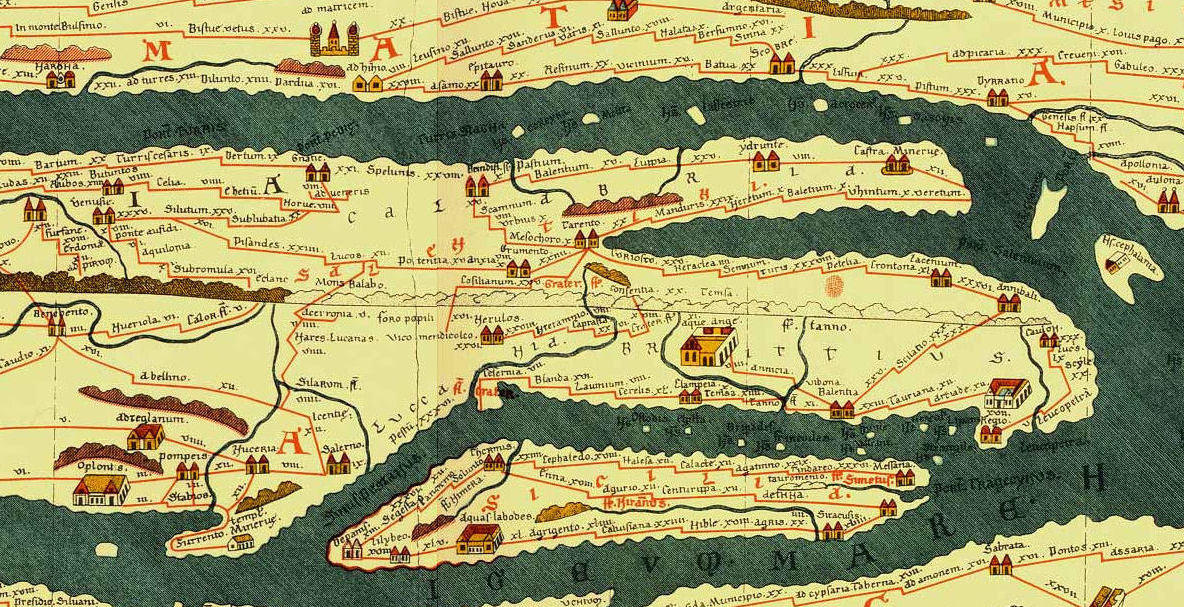

Se c’è un luogo dove sul tracciato dell’Appia non ci sono dubbi, ce lo abbiamo davanti. Lo dicono gli itinerari romani, la Tabula Peutigeriana, le carte IGM del secondo dopoguerra. […] Scavalchiamo le recinzioni, rimontiamo i terrapieni e camminiamo contromano tra i guardrail come lagunari, sfiorati da automobilisti allibiti. […] Ecco dove l’archeologia diventa intralcio per l’italico potere cementizio. Per questo, anche in Apulia, l’Appia è apertamente ignorata dai sindaci e dai loro tirapiedi. Più comodo far finta che non ci sia. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

The traveller, who is following this itinerary on foot, by train or by other means, once arrived in Altamura will be fascinated by this centre populated since prehistoric times. Just in the countryside of this rich agricultural town the first and only intact and complete prehistoric hominid skeleton was discovered and is known as the Man of Altamura.

We recommend a visit to the historical centre of the town with its majestic Cathedral and finally a walk through the narrow streets and its cloisters, which Rumiz describes as follows:

Altamura vecchia è acustica del labirinto allo stato puro. Trillo biforcuto di rondoni, solitario canto greco di donna, fruscio di panni stesi. Luce violenta, che ti spinge a parlare sottovoce anziché a gridare più forte. Passeri che tacciono, aspettando la sera. Enormi nubi immobili nonostante il vento. […] Il genius loci aborre il rombo dei rettilinei e si rintana nei “claustri”, piazzette nascoste, dove regna un borbottio claustrale, da accademia talmudica. Diverticoli che ripetono il motivo del grembo femminile. Altamura è una “polis” in miniatura, che si rintana in mille viottoli. Non guarda all’esterno, ma verso il proprio centro. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

From the labyrinthine Altamura, with its cloisters, small courtyards in which votive shrines are often still set up, and which suddenly open up between the narrow alleys, we continue our journey towards Taranto.

Our journey following the one of the writer, which has become our guide on the Via Appia, continues through the lands between Puglia and Basilicata. After crossing the municipalities of Laterza and Castellaneta, we eventually begin to see the Ionian Sea and unfortunately also Ilva, the huge iron and steel plant that stands at the gates of Taranto.

This is the story of Paolo Rumiz’s arrival in the city:

[…] oltre una distesa di agrumeti, al termine di un lungo piano inclinato, appare la striscia cobalto dello Jonio, il più greco dei mari. E, poco a sinistra, sotto una massa di nubi portatrici di pioggia, un’altra visione. Inquietante. Una cresta dentata che fuma, come quella di uno stegosauro, trapassata dai fulmini, immensa eppur lontanissima. L’Ilva.

Ci aspetta sornione, a fauci spalancate, in fondo alla nostra strada. Si è disteso apposta sul cammino dell’Appia Antica col corpo smisurato e la pancia abitata dal fuoco perenne. Tra noi e Taranto è l’ultimo ostacolo. Un passaggio obbligato, come la Sfinge dei Greci, come il Maligno appostato sui ponti delle fiabe. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

Even the traveller who is following this route, before being able to appreciate the beauties of the Ionian capital, will have to overcome the “Sphinx”, pass the blanket of smoke that surrounds the city, which was once the terminus of the Appian Way, before Brindisi became the terminal. In all likelihood he will have to circumvent the abandoned reddish buildings of the Tamburi district, where workers of the iron and steel factory were staying and which, as a mirage of development and well-being, soon turned out to be a very dangerous nightmare for the population and the environment. However, Taranto is not only Ilva. With its scenic location on a natural inlet of still crystal clear waters, the city will astonish the traveller, as Rumiz explains:

Ma ecco Taranto Vecchia, aggrappata all’isolotto che fa da intercapedine tra il Mar Grande e il Mar Piccolo. Reti colorate alla greca, odore di pescheria di una volta, vicoli più autentici che a Sorrento, popolane sfrontate, case che il tempo ha lasciato invecchiare in pace. […] Sul lato della città nuova, due poderose colonne doriche, di gran lunga anteriori alla tracciatura dell’Appia, snobbano il presente voltando le spalle all’acciaieria e dicono che la storia di Taranto che conta è tutta anteriore al dominio romano. Taranto significa una grande epopea ignorata. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

This Tarantine epopeia, according to legend and myth, began around 2000 BC., when Taras, Poseidon’s son, would have arrived in the city on the back of a dolphin. According to Strabo, a Greek geographer and historian who lived at the end of the 1st century BC, it was a group of Spartans led by Falanto who founded Taranto in 708 BC.

In the last decades of the fourth century, the city was one of the most powerful and prosperous colonies in Magna Graecia, as evidenced by the exports of vases and ceramics throughout the Mediterranean and the numerous capitals that were mobilised to erect incredible works of art and refined products of goldsmith’s art, today exposed in the Marta Museum, one of the Italian and European museum excellences.

Let us enter its halls following the story narrated by Rumiz:

[…] è vietato andarsene da Taranto senza aver visto il museo archeologico. All’ex-convento dei frati alcantarini si deve andare semplicemente perché ce lo ordina la bellezza, e la bellezza se ne frega se Roma è distratta e lontana, se a Taranto non arriva nessun Frecciarossa e non c’è aeroporto. […]

In quelle sale venerabili abita una delle meraviglie d’Europa. Un’antichità che non è marmo freddo ma scintillio di ori e argenti, gioielleria greca sepolta e riemersa dalle necropoli del IV e III secolo avanti Cristo. Taranto delle grandi botteghe degli orafi, Taranto trionfo di un universo femminile che Roma è ancora lontana dal concepire. Taranto dagli orecchini a navicella tintinnanti di pendagli, dalle foglie d’alloro e dai petali rosa in lamina d’oro zecchino. Taranto degli anelli, dei monili, delle teste di leone, fucina di smalti favolosi, cristalli di rocca, granulati d’oro, anelli, cammei e raffinati sigilli. (P. Rumiz, Appia)

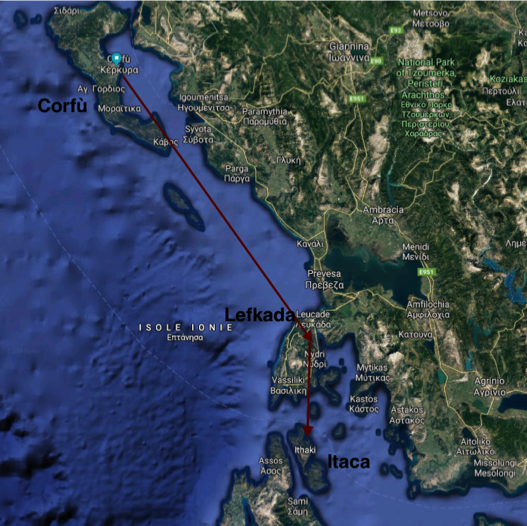

After admiring the splendours of Taranto’s past guarded at Marta, the traveller is now left to continue his journey along the Appian Way to reach Brindisi; with its port the city of Brindisi is still today, as in the past, one of the embarkation points par excellence towards the East and Greece. On one of the ferries which connect the city of Alto Salento to Greece, we leave Puglia to land in the Ionian Islands. The crossing will last only one night and at dawn the traveller will be able to see from afar the island that has always been identified as Scheria (Phaeacia): Corfu. It took eighteen days for Ulysses to reach it, after leaving beautiful Calypso in Ogygia.

With the Odyssey in hand, in its poetic translation by Ippolito Pindemonte, a scholar and poet with solid classicist foundations yet close to the pre-romantic sensibility who lived at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Ulysses’ arrival in Corfu will introduce us to the Homeric dimension of this last part of our itinerary.

Lieto l’eroe dell’innocente vento,

La vela dispiegò. Quindi al timone

Sedendo, il corso dirigea con arte,

Né gli cadea su le palpèbre il sonno

Mentre attento le Pleiadi mirava,

E il tardo a tramontar Boòte e l’Orsa

Che detta è pure il Carro, e là si gira,

Guardando sempre in Orïone, e sola

Nel liquido Oceàn sdegna lavarsi

L’Orsa, che Ulisse, navigando, a manca

Lasciar dovea, come la diva ingiunse.

Dieci pellegrinava e sette giorni

Su i campi d’Anfitrite. Il dì novello

Gli sorse incontro co’ suoi monti ombrosi

L’isola de’ Feaci, a cui la strada

Conducealo più corta, e che apparìa

Quasi uno scudo alle fosche onde sopra.

(Odyssey, V, 346-361.)

(R. Nicolì, Introduction to Viaggio in Grecia by Saverio Scrofani, POLYSEMI Digital Library)

As he wrote:

Finalmente, dopo otto giorni di navigazione, ecco le Montagne dell’Epiro, ecco gli scogli Acrocerauni, ecco Corfù. A questi nomi mille idee mi si affollarono in mente: Alessandro, Pirro, Nausica, Alcinoo, Ulisse occuparono ad un tratto la mia fantasia: io non mi stancava di riguardare da lontano quelle rocche e quei monti così famosi. (S. Scrofani, Viaggio in Grecia, Letter V)

In these verses we can follow Odysseus who is happy at the helm of his raft oriented through the stars, as advised by beautiful Calypso, always keeping the Chariot to the left, the only star that never changes position. On the eighteenth day, the shady mountains of the Phaeacian island appear.

The arrival on the Greek coasts has always aroused an incredible emotion in the writers of every age, who above all between Enlightenment and Romanticism chose Greece as the ideal home of Western culture. Let us read for example the emotion of the Sicilian prolific intellectual Saverio Scrofani as he saw the Ionian Islands on the horizon during his 1794 journey undertaken in the wake of the Enlightenment Grand Tour, with a look at ancient Greece that «anticipa l’adesione lirica che il mito dell’Ellade conoscerà nei grandi romantici europei». (R. Nicolì, Introduction to Viaggio in Grecia di Saverio Scrofani, POLYSEMI Digital Library). As he wrote:

Finalmente, dopo otto giorni di navigazione, ecco le Montagne dell’Epiro, ecco gli scogli Acrocerauni, ecco Corfù. A questi nomi mille idee mi si affollarono in mente: Alessandro, Pirro, Nausica, Alcinoo, Ulisse occuparono ad un tratto la mia fantasia: io non mi stancava di riguardare da lontano quelle rocche e quei monti così famosi. (S. Scrofani, Viaggio in Grecia, Letter V)

Still today when coming to Corfu by ship the traveller can observe the looming of the Albanian mountains on the horizon – which excited Scrofani and which we like to imagine as the same shady mountains that Ulysses saw – and, entering the port, the gaze will be captured by the bulk of the Old Venetian Fort with its ramparts on the sea.

As he landed on these shores, Ulysses met beautiful Nausicaa who took him to the city in the palace of his father Alcinous, king of the island. There are many places here that compete for the primacy of having been the theatre of this first meeting; among them are Paleocastrizza on the west coast, about thirty kilometres far from the city of Corfu and, on the east coast, the bay of Kanoni.

Once landed in Corfu, the traveller can only start wandering around Kerkyra, the main centre of the island, in an attempt to recognise the city of the Phaecians.

As described in the Odyssey:

È la città da un alto

Muro cerchiata, e due bei porti vanta

D’angusta foce, un quinci e l’altro quindi,

Su le cui rive tutti in lunga fila

Posan dal mare i naviganti legni.

Tra un porto e l’altro si distende il foro

Di pietre quadre, e da vicina cava

Condotte, lastricato; e al fôro in mezzo

L’antico tempio di Nettun si leva.

(Odyssey, VI, 366-373)

Nothing remains of the high walls sung in these verses or of the paved hole and even less of the temple of Neptune neither in Kerkyra nor in the other towns of the island – to the point that the cultured Sicilian traveller Scrofani struggled to hide the disappointment and wrote:

[…] dove son dunque i resti della reggia e de’ giardini d’Alcinoo? Non si vede più nulla. Il tempo distrugge, è vero, le fabbriche e le coltivazioni; ma le fonti, ma i fiumi che le irrigavano dove sono? Temo che tutte le bellezze e le magnificenze d’Alcinoo, le porte d’oro, le mura d’argento, i chiodi di gemme, non siano un effetto della fantasia d’Omero come le statue ch’ei fa lavorare per lo scudo d’Achille. Se si vuole prestar fede al racconto del poeta, qui presso era il luogo dove Ulisse fu rigettato dalla tempesta; qui ha dovuto nascondersi e qui mostrarsi nudo alla figlia del re. Ecco la fonte dove Nausica lavava i panni quando il re d’Itaca le si scoperse, quando ella se ne innamorò, quando le sue ancelle lo rivestirono dopo aver in un segreto abboccamento ottenuta la protezione della padrona. Ma come è possibile che Ulisse, giunto in Feacia, non sapesse riconoscere le montagne dell’Epiro che le stanno in faccia, né la stessa Leucade che doveva quasi scoprire co’ propri occhi? Di più: Ulisse, un re, un viaggiatore, un eroe che ritorna dopo aver distrutto il regno di Priamo, ignora poi qual popolo abiti in quell’Isola e quali sieno i Feacesi? Eppure Corfù non è distante che 100 miglia da Itaca. Misero colui, che ardisse oggigiorno scrivere un poema su questo gusto. Che dico? Felice chi potesse solamente imitarlo. (S. Scrofani, Viaggio in Grecia, Lettera X)

Never mind if the traveler arrived in Corfu will not see the traces of Alcinoo’s palace as happened in Scrofani,: the island and the city will still be able to enchant him with their Venetian and Oriental charm, their incredible landscape and beautiful beaches.

There is another place closely related to the Homeric tale: the islet of Pontikonissi, a few kilometres south to the centre of Kerkyra. According to a tenacious tradition it would be the ship by which the Phaeacians brought Ulysses back to Ithaca. It is said that Poseidon petrified and sank the boat here out of revenge, when they came back home.

The verses of book XIII from the Odyssey describe the moment in which the God of the Sea, after talking to Zeus, operates the prodigy and, after approaching the ship and with a touch of hand, turned it into stone – into what the legend wants it to be today precisely known as the rock of Pontikonissi:

“[…] quando

I Feacesi scorgeran dal lido

Venir la nave a tutto corso, e poco

Sarà lontana, convertirla in sasso

Che di naviglio abbia sembianza, e oggetto

Si mostri a ognun di maraviglia; e in oltre

Grande alla lor città montagna imporre”.

Lo Scuotiterra, udito questo appena,

Si portò a Scheria in fretta, e qui fermossi.

Ed ecco spinta dagl’illustri remi

Su per l’onde venir l’agile nave.

Egli appressolla, e convertilla in sasso,

E d’un sol tocco della man divina

La radicò nel fondo. Indi scomparve.

(Odyssey, XIII, 188-201)

The traveller will decide whether to believe this legend or not; however, it is an absolutely advisable experience to visit this high cliff on the sea, surrounded by a cypress grove, reachable by boat from the pier where the white Monastery of Vlacherna of the seventeenth century is located.

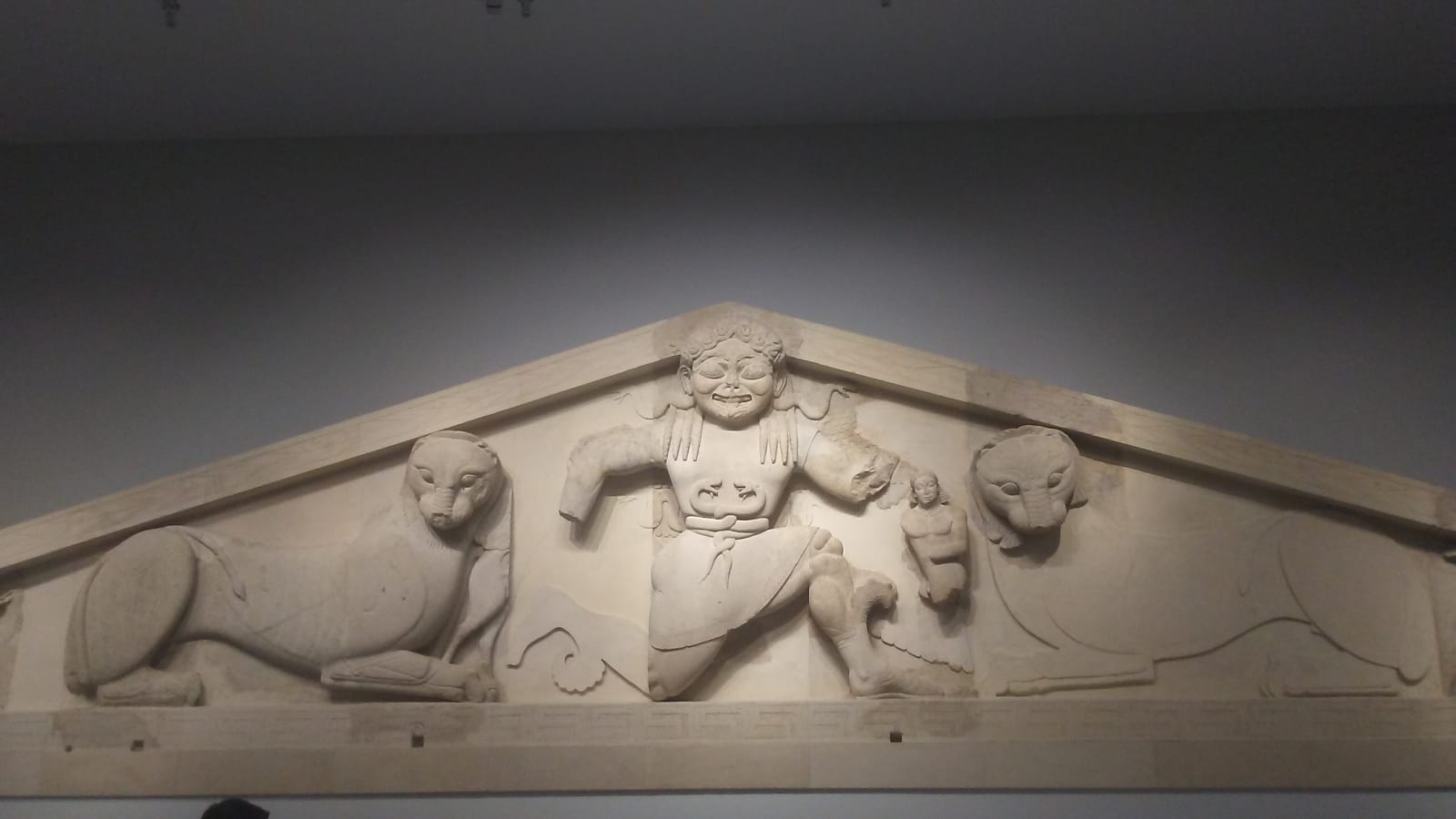

Before leaving Corfu and continuing the itinerary towards the island of Lefkada and finally towards ‘rocky’ Itaca, we advise the traveller to visit the Villa Mon Repos which hosts an interesting archaeological collection with finds from the ancient area of Paleopolis and the Archaeological Museum located in via Vraila Armeni n.1. Here, among other interesting finds, the pediment of an archaic temple dedicated to goddess Artemis is preserved and exposed, bearing the impressive mythological figure of one of the Gorgons, according to the British poet and writer Lawrence Durrell, the famous Medusa.

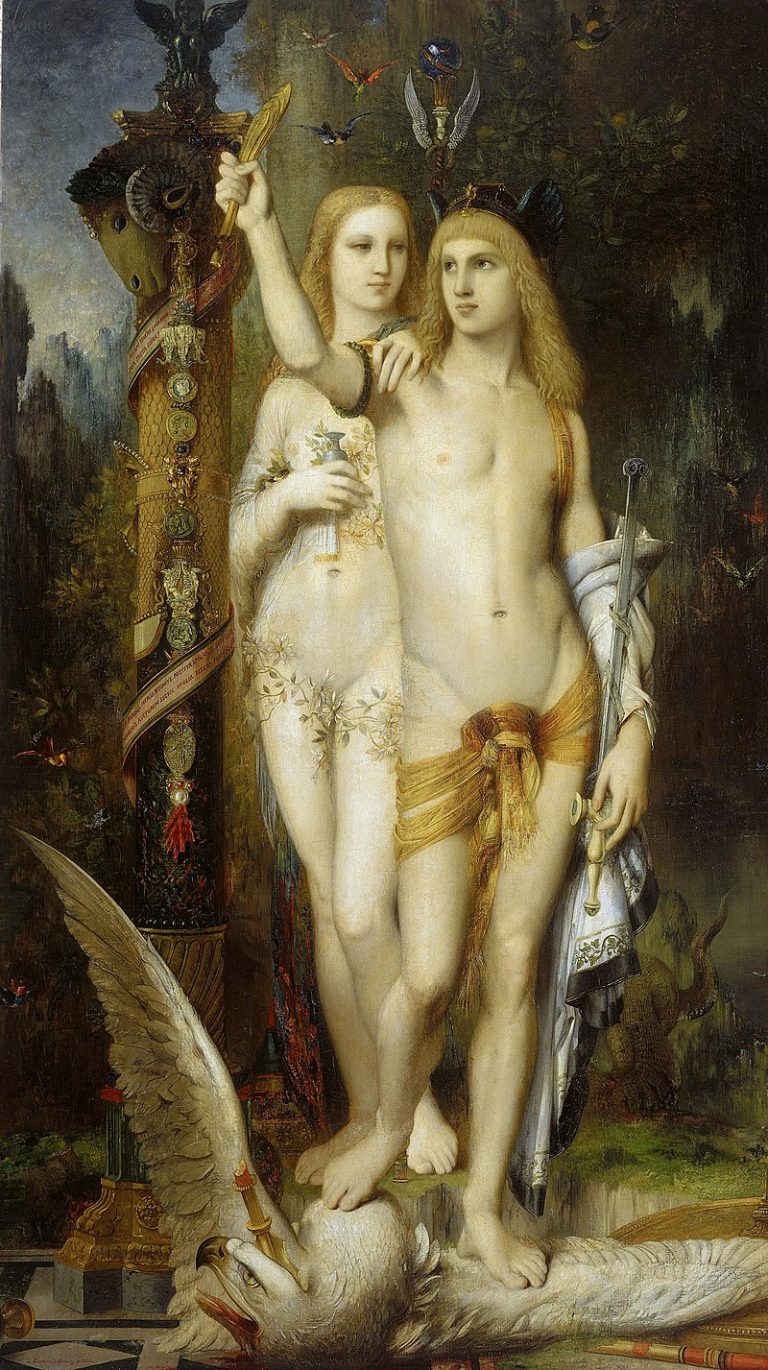

Here in Corfu is the story of another terrifying woman of classical mythology, Medea, who got married on the island, with Jason, the traveling hero wandering all over the Mediterranean in search of the golden fleece together with the Argonauts. According to mythology it was Alcinous himself, the king of the Phaecians, who welcomed Medea and Jason to the island and made them marry. The wedding was followed by an intense night of love. It is precisely during that night that Medea, the famous film by Pasolini starring Maria Callas, begins.

Now what the traveller is left to do is to follow Ulysses’ example and continue the journey. Although the beauties of Corfu invite you to stay, the time has come to set sail and continue our itinerary of myths and heroes towards Lefkada, taking advantage of the connections by sea that are made available for the Ionian Islands. Along our route we will come across the two small islets of Paxos and Antipaxos. You do not need to touch the ground to encounter myths and history again. Not too far from the waters we are sailing, one of the most famous battles of the ancient world was fought, i.e. the battle of Actium, where the dreams of love and power between Antonio and Cleopatra broke. Legend has it that the two lovers feasted on these islets on the eve of the fatal battle. This stretch of Ionian sea is also a jewel of biodiversity, where it is possible to admire some rare marine species such as the hawksbill turtle and the monk seal.

We arrive in Lefkada, which is called Santa Maura by Venetians. Today the island is famous for its pristine beaches and for being a favourite destination for walkers and hikers.

In addition to its natural beauty, in the Classical and Romantic imagination Lefkada is famous for its white cliffs immortalised by painters and sung by many poets; it is from these cliffs that the poet Sappho decided to throw herself into the sea to end her tormented love with Phaon.

Saverio Scrofani is clearly excited as he writes the report of his 1794 trip to Greece in the form of an epistolary report which was published in 1799:

Al far del giorno ci trovammo in faccia a’ famosi regni d’Ulisse: questa è Leucade, quella è Itaca, quella è Ceffalonia, quello è il Zante. Ecco il capo Colonna e le ruine del tremendo tempio d’Apollo. […] dall’alto di quello scoglio che sto osservando co’ propri occhi, che biancheggia da lontano e spaventa, in quel mare profondo che si frange a’ suoi piedi, funesto sempre a’ nocchieri e sempre agitato, si precipitò e perì ebria d’amore, di dispetto, di noia la divina, la sensibile, l’appassionata Saffo. E i Sacerdoti, gl’interpreti, i ministri de’ numi avevano inventato quest’assassinio? E i numi che amavano l’umanità e l’innocenza, i numi che punivano le altrui sceleraggini lasciarono sussistere per più secoli quest’esempio della lor tirannia e della loro impotenza? O come ti vedrei volentieri, Faone, in mezzo a Tizio ed a Sisifo pagar la pena della tua durezza: ti vedrei rodere… Ma questo rimprovero è sicuramente un’ingiustizia, un effetto della mia fantasia riscaldata. Qual colpa ebbero Faone, i preti, i numi? L’uno non poté amar Saffo, e quando non si può non v’ha colpa; gli altri la tolsero dagli affanni che soffriva amando chi non l’amava: in effetto la morte è il solo efficace rimedio per un amore non corrisposto. Alle porte d’ogni città, si dovrebbe trovare un salto di Leucade: gli amanti disperati ritornerebbero saggi o finirebbero di penare, e i governi sarebbero più tranquilli. (S. Scrofani, Viaggio in Grecia, Lettera XI)

It is said that the ancients believed that one could directly reach the underworld or at least the river Acheron by jumping from these cliffs. In fact, according to Strabo, it seems that the dive from the Lefkada cliff was a fairly common practice in classical antiquity and that Apollo’s priests performed it regularly. The jump, which probably also had some propitiatory function, was called Katapontismos.

We leave his romantic cliffs of Saffo to reach the longed-for destination of Ulysses’ journey and the last part of our journey.

In verses 26-33 of Canto IX of the Odyssey, Ithaca is briefly described as follows: its landscape is dominated by the high Monte Nerito, on which the winds break; it is surrounded by the neighbouring islands most moved to the East, like luxuriant Zakynthos. The earth is harsh and mountainous, yet good nurturer of young people:

[…] dove

Lo scotifronde Nérito si leva

Superbo in vista, ed a cui giaccion molte

Non lontane tra loro isole intorno,

Dulichio, Same, e la di selve bruna

Zacinto. All’orto e al mezzogiorno queste,

Itaca al polo si rivolge, e meno

Dal continente fugge: aspra di scogli,

Ma di gagliarda gioventù nutrice.

(Odyssey, IX, 26-33)

What is left to do is to suggest the traveller who wants to experience the Homeric dimension of the island some excursions in the surrounding area. Moving about 10 km south of Vathy, the main centre of Ithaca, near the village of Anemothouri, one can encounter the true or alleged Arethusa source, that is, where Ulysses in the Odyssey is said to have met his trusted servant Eumaeus, who used to go there to let the pigs water.

The path, albeit not always easy, offers panoramas and very suggestive views. A simple blue sign indicates the site where the source is located.

Another place we suggest to visit is the natural ravine, near the famous beach of Dexa, known as the grotto of the Nymphs, “the convex cavern”, where the hero made sacrifices in honour of the divine creatures. Here you can also improvise new Indiana Jones in search of the treasures that Ulysses is said to have hidden near the cave. By reading the verses of the Odyssey that sing this place, the traveller will be able to recognise the landscape, which is characterised by the fronds of the olive trees that still today embellish this stretch of the Iacese coast sacred to the nymphs called Naiaids; between amphorae and vases where the bees produce honey, they weave purple drapes of incredible beauty on marble looms.

As Homer sang:

[…] Spande sovra la cima i larghi rami

Vivace oliva, e presso a questa un antro

S’apre amabile, opaco, ed alle ninfe

Nàiadi sacro. Anfore ed urne, in cui

Forman le industri pecchie il mel soave,

Vi son di marmo tutte, e pur di marmo

Lunghi telai, dove purpurei drappi,

Maraviglia a veder, tesson le ninfe.

(Odyssey, XIII, 126-132)

Finally, we head to Mount Aetos, near the small village of Alalkomenés. On this summit, the famous archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann was able to find the city of Troia with the Iliad in his hands; he also managed to find the remains of Ulysses’ palace. There are still no archaeological evidences to confirm this hypothesis, but based on recent excavations, another place in Ithaca has become a candidate for the site where the Greek hero’s palace would be.

Near the small village of Stavròs, on the small hill of Pelikata, in the northern part of the island, among hills covered with olive trees and planted with vines, near a small archaeological museum, the remains of a palace with Cyclopean age walls have been identified dating back to the Mycenaean era; we like to imagine that long ago it was able to certainly host some noble warrior or aristocrat, if not Ulysses and faithful Penelope.

Qui dunque visse, quell’uomo eloquente, e in conseguenza artificioso, che dopo aver fatto il pirata fra questi scogli infecondi, fu poi cagione in Asia della strage e del pianto di migliaia d’uomini e di cui Omero ha fatto un eroe? Qui i Proci assediavano Penelope, qui visse Telemaco, qui Mentore filosofava, qui scese Minerva a proteggere Ulisse, a conversare con lui? (S. Scrofani, Viaggio in Grecia, Letter XI)

Let us conclude at the end of this itinerary, as Scrofani suggests, that “I geografi, egl’istorici ne disbrighino la questions far loro”, since, after paraphrasing some verses of the Greek poet Kostandinos Kavafis, we are certain that even without having the answers to our Homeric doubts:

[…] non per questo Itaca ti avrà deluso

Fatto ormai savio, con tutta la tua esperienza addosso

già tu avrai capito ciò che Itaca vuole significare.

(K. Kavafis, Itaca)