THE SECOND EXILE

Niccolò Tommaseo’s writings concerning the things of Italy and Europe from 1849 onwards

Volumes 1-2-3

A selection of letters and texts written during his Corfiota stay

Introduction by R. Nicolì

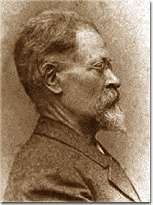

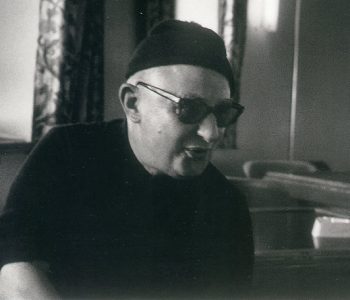

This digital edition produced for the POLYSEMI Library proposes a significant sampling – albeit arbitrary to some extent – of the letters sent by Niccolò Tommaseo[1] during the time spent in Corfu, where he moved in August 1849 after the fall of the Venetian Republic of which he had been one of the most ardent defenders. On the island the writer remained until May 1854. This is his “second exile”[2], as he entitled the three volumes of the memoirs of those years entrusted in 1862 to the Milanese publisher Francesco Sanvito. From that edition the parts presented here have been selected and transcribed.

We have to say that it was a voluntary exile: the destination was chosen, as he himself affirms with awareness and emotional enthusiasm: “E già era una prova d’affetto anco il dimorare tra voi per quattr’anni potendo scegliere il soggiorno d’Inghilterra, di Svizzera, di Francia, del Piemonte, dove ho conoscenti e amici sinceri, che per quello spazio di quattr’anni non cessarono d’invitarmi a venire.”[3]

Niccolò Tommaseo experienced the history of Greek independence with particular involvement, considering Greece as another homeland of which he loved the language, the history, the spirit, the people and every single event. Well before this long period spent there, he had in fact tightened and cultivated friendships with Greek writers and scholars, relationships genuinely based on intellectual harmony and on mutual and constructive influence and, after his Corfiot experience, he took advantage of his own studies and research with his translation of Greek folk songs[4] which represent the maximum expression of his love for that land, thus contributing to the spread of Greek culture throughout Italy.

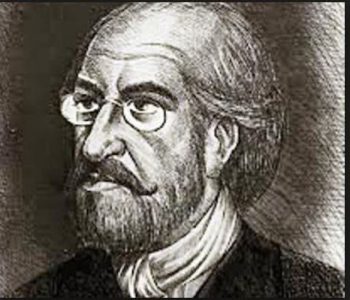

The relationships between Italian and Greek intellectuals, many of whom came from the Ionian Islands, on the other hand, were rooted in the renewed Enlightenment climate of the previous century: the university cities and the most active publishing centers (e.g. Venice, Padua, Pavia, Milan) were meeting and discussion places where talks and publications on the conflicting Greek events took place. At the beginning of the 19th century Andreas Mustoxidis, Dionisios Solomos, Ioannis Karasutsas, Dimitrios Paparrighopulos, Andrea Calvo and, among the Italians, Ugo Foscolo and Niccolò Tommaseo were included in the most active circles.

In 1821, following the outbreak of the Greek revolution against the Turkish domination and the liberation war of Greece, educated Europe not only provided its financial support but also addressed the public opinion with works full of admiration for the heroism of Greek people. After the failure of the 1820-21 revolts in Piedmont and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, many Italians tried to implement their unrealized revolution in Greece, shifting aspirations and ideals to Greek events and creating the conditions for an even stronger association between Greek and Italian intellectuals, as Ippolito Nievo asserted in Le Confessioni d’un Italiano: “Ecco ch’io ho diviso il mio cuore fra le due patrie più grandi e sventurate che uomo mai possa sortire nascendo. … A Corfù s’imbarcarono parecchi Italiani fuggiti da Napoli e dal Piemonte che si proponevano di versar per la Grecia il sangue che non avean potuto spargere per la propria patria..”[5]

The exiles who arrived in Greece had an idealized image of the land that would welcome them: the one that had been presented to them by the philhellenic movement and by the political exponents of the Risorgimento, but also by the Italian neoclassical and romantic literature. At that time, Italy needed a model of national struggle and the admiration for the splendor of ancient Greece supplemented by the idealization of the modern heroism of the Greek people. Episodes such as the sortie of Missolungi, the massacre of Chios, the struggle of Souli against despotism and tyranny, the naval battle of Navarino, the establishment of the Bavarian monarchy, together with the individual vicissitudes of the heroes of the Greek liberation revolt like Botsaris, Rigas, Canaris, Byron, Santarosa, the latter being the author of the Scritti sulle Isole Ioniche by Foscolo,[6] dominated the patriotic literary production during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Almost thirty years later, when Tommaseo settled in Corfu, the struggle for Greek independence and the Italian Risorgimento were even more distinctly marked by interactions and solidarity.[7]

Unlike the 1820-21 exiles which were largely aristocratic, the new flow of Italians towards Greece was largely made up of bourgeois: many of them were lawyers or doctors, many scholars were not appreciated by the Austrian government. Most of them chose to stay on the Ionian Islands, whereas the rest settles in the newly born Greek state. On the Ionian Islands, which remained free from the Ottoman domination and had been part of the Republic of Venice until the fall of the latter, they knew they would find an extremely favorable environment. After various ruling powers had succeeded one another on the Ionian Islands in Napoleon’s unstable Europe, since 1815 the Heptanese had passed under British protectorate. The long presence of administrators sent by Venice, the Venetian right, the use by wealthy families to send their children to study in Italy, had kept alive the Italian character of the islands a few decades after the end of the Venetian domination.

In the Corcirese years, Tommaseo was certainly the most authoritative and intellectual figure in the community of exiles, although he is known to have lived in tragic economic and spiritual conditions, mitigated by his marriage with Diamante Pavello .

In the meantime, Italian philanthropy had taken on distinctive characteristics compared to other European countries and, in the host country, the Italian exiles were on the side of the Greeks who rebelled against the Turks, fighting and offering their aid in medical assistance, logistics and administration, but also by contributing to the insurrectionist press. There is, and it must be emphasized, also a more emotionally participated approach, traceable in the obvious interest in daily life, religion, language, scientific production and cultural activity. In this sense the letters of Tommaseo provide valuable information, although the recipients are omitted according to a publishing norm of the time.

Of the three volumes, each consisting of more than 400 pages, the most conspicuous part proposed here is taken from the first volume, which more than the others contains short letters and articulated dissertations on general topics that embrace different themes, from the possible reforms of the Ionian Islands school system to administrative reforms, from the presence of two different religious rites in Corfu to the problems deriving from their coexistence, from scholarly considerations on the lines of the Greek people and the Corcirese dialect to the proposal to give all Slavic peoples a language, a proposal that takes its cue from the considerations that the language of Greece, Italy and the Ionian Islands displays points of convergence with the linguistic issues of the Slavic world.[8]

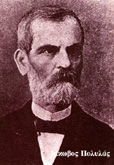

Of the second volume, which mainly deals with issues related to Italian politics, the state of education in Italy and the outcome of the insurrection wars, we decided to propose two parts that are considered more significant than others and representative of Tommaseo’s relationship with the Ionian Islands: a letter sent to the people of Corfu and a eulogy of Solomos, the composer of the Greek National Anthem.

As regards the letter to the People of Corfu, which is perhaps rather an appeal, Tommaseo’s need to address the Greek people who hosted him was determined by a misunderstanding of his text, with eloquent and certainly controversial features, published shortly before and concerning the protocols of justice applied on the island. Tommaseo had officially expressed his own opinion against death penalty in his Il Supplizio d’un Italiano a Corfù,[9] a narrative inquiry into a judicial error which recalls the history of the infamous Manzonian column and which was considered offensive even by numerous Corfiots who had been Tommaseo’s admirers and supporters. Among those who condemned the story there were also friends of the author, such as Mustoxidis, a prominent figure and emblem of the cultural association between Italian and Corfiot intellectuals in those years, as well as Niccolò Beltrami Manessi, the author of historical studies and future first mayor of Corfu. The latter published, in the newspaper “Εφημερίς των ειδήσεων”, four articles against Tommaseo, accusing him of deliberately discrediting the people of Corfu with his Supplizio d’un Italiano. In the appeal of which we propose the most significant passages here, Tommaseo tries to justify the intentions of his work and to demonstrate that his accusers had unjustly pointed him out as ungrateful host of the island. The writer invites all Corfiots to approach his text directly without any criticism, as he is convinced that his words are enough to deny any accusation.

The praise by Solomos is instead a sincere homage to his friend, but implicitly also to the whole Heptanese who had given birth to the formation of the noble Greek national poet. Between the two there was a friendship destined to last even after Tommaseo’s return in Italy and above all aimed at marking important collaborations: this is the case of the collection of Greek folk poems that the Dalmatian writer realized thanks to the materials that Solomos managed to find and send. Solomos, on the other hand, was interested in Tommaseo’s studies already a decade before his stay in Corfu, when he was in Paris. For him, Tommaseo was the best person to introduce the greatest philology to the University of Athens and, for Tommaseo , Solomos was the greatest Greek poet of his era.

As regards the third volume, we have chosen to propose two relevant passages: the praise of Aristotle Valaoriti and the moving Greece and Italy.

The reports that linked Tommaseo to one of the greatest poets of the Heptanese, Aristotelis Valaoriti, beside the pages dedicated to him in the Second Exile, are backed up by a close correspondence between the two: the politics of the two countries, the journeys and the respective family situations, the observations on the issue of language and poetry.

In the years when Tommaseo is in Greece, literary production is experiencing a dark period, perhaps due to the passive importation of degenerated romanticism. All of this unfortunately caused an arrest in the cultural progress of the country and Tommaseo , who personally witnessed this degeneration, tried to push the Greeks, including Valaoriti himself, to turn to popular poetry and to look for sources for a regeneration of the cultural and literary tradition.

In the last extract we propose, which closes the present digital edition, Tommaseo emphatically exposes the parallelism between the Italian and the Greek situation, which is everywhere expressed in the volumes. To the admiration for the popular unity manifested in the struggle, the author associates a wish that goes beyond the contingent situations of conflict and recalls the bonds of the deepest and most common roots to the two peoples: “Ma che la Grecia, la maggiore sorella all’Italia nella civiltà e nel retaggio delle arti gentili, la Grecia per secoli divisa da noi forse perché divisa in sé stessa, risenta così ardente, come ora fa, l’amore fraterno; questo, al mio vedere, è trionfo più splendido che qualsiasi vittoria guerriera, e segna una nuova età nella vita de’ due Popoli, che della vita dell’intero genere umano è stata e sarà non piccola parte”.

-

For a detailed biography of Tommaseo, in addition to the DBI online resource http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/niccolo-tommaseo/ , see also R. Ciampini , Vita di Niccolò Tommaseo, Sansoni, Florence, 1945. ↑

-

A first voluntary exile took place in France from 1834 to 1838. The following year, Fede e bellezza came out , the “novel of exile”, the fruit of that experience. ↑

-

The passage is contained in the letter to the People of Corfu , contained in vol. 2 of the Second Exile and reported in the most significant excerpts in this digital edition. ↑

-

N. Tommaseo, Canti popolari toscani, corsi, illirici e greci , from Girolamo Tasso’s typographic encyclopedic establishment, Venice 1841-42, 4 vols. (Bologna, Forni, 1973). ↑

-

I. Nievo, Le Confessioni d’un Italiano, edited by S. Casini, vol. 2, P. Bembo Foundation -U Guarda Editore, Milan-Parma, 1999, p. 1295. ↑

-

Also this work has been included in the POLYSEMI Library. ↑

-

On the Italian political emigration of the Risorgimento, see: A. Galante Garrone, L’emigrazione politica italiana del Risorgimento, «Rassegna storica del Risorgimento», XLI (1954), pp. 223-242; MA Fonzi Columba , Emigration, in VV.AA., Bibliografia dell’età del Risorgimento, in honor of A. Ghisalberti, vol. 2, LS Olschki, Florence, 1972, pp. 427-469; C. Ceccuti, Risorgimento greco e filoellenismo nel mondo dell’«Antologia», in VV.AA., Indipendenza e unità nazionale in Italia ed in Grecia. Study Conference, Athens, 2-7 October 1985, LS Olschki , Florence, 1987, pp. 79-131; E. Michel, Esuli italiani nelle Isole Ionie (1849), «Rassegna storica del Risorgimento», XXXVII (1950), pp. 327-344. ↑

-

The result of studies and research on the subject were the 4 volumes entitled Canti popolari toscani, corsi, illirici, greci, raccolti e illustrati da Niccolò Tommaseo, G. Tasso, Venice, 1841-1842. ↑

-

[9] N. Tommaseo, Supplizio di un Italiano a Corfù, Barbera, Bianchi and Comp ., Florence, 1855. A recent reprint is by F. Danelon , with a study by T. Ikonomou , Venice, Istituto Veneto di Scienze , Letters and Arts, 2008. ↑