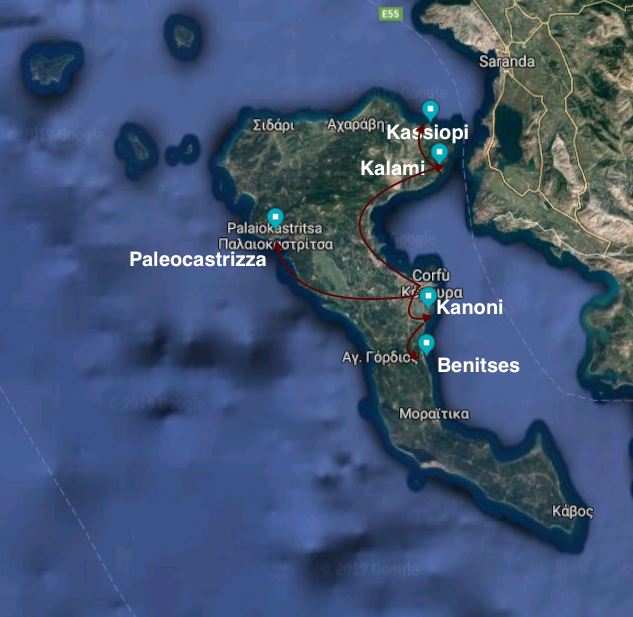

Corfu: Benitses, Kanoni, Kassiopi, Palaiokastritsa, Kalami.

The island of Corfu, which has always attracted many travelers due to its natural and artistic beauties, is also one of the most appreciated and described islands by writers. Authors have written a lot on this beautiful Greek island, from Homer – and the identification of Corfu with Scheria, the land of the Phaeacians −, Boccaccio and Shakespeare – who imagined it as the setting of The Tempest – to the twentieth-century writers Cecchi, Romano and Mario Praz, to name but a few. In particular, the brothers Gerald and Lawrence Durrell, who had moved from England to Corfu in 1935, were enchanted by it. The youngest, Gerald, who would have become a renowned naturalist, set a successful book on the island: My Family and other Animals. This novel has been the basis for a TV series recently, which has been acclaimed by the audience and critics. Lawrence, the eldest brother, an internationally renowned writer and poet, made Corfu the protagonist of some of his best known literary masterpieces, like Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra (Corfu) and The Greek Islands. The beauty of Corfu impressed also the famous American writer Henry Miller, who visited Lawrence Durrell on the island in 1939. The reminiscences of that experience, which led the author to travel all over Greece for nine months, gave birth to his book The Colossus of Maroussi, a sort of travel journal.

In this short itinerary we suggest the traveler discover the charm of Corfu that enchanted these writers, retracing the places described in their books.

However, we warn the traveler that the charm and atmosphere we are looking for – as Gerald Durrell pointed out – were summed up on some British Admiralty maps, which showed: “in grande l’isola e la costa limitrofa. Infondo c’era una piccola leggenda che diceva: AVVISO: poiché le boe che segnalano le secche sono spesso fuori posto, si raccomanda ai naviganti di stare in guardia quando si rasentano queste coste” (G. Durrell, La mia famiglia e altri animali)

For many travelers, including our writers, the discovery of Corfu beauty starts from the sea, when they are going to land on the island and can make out its outlines from the ship deck or their cabin window.

Gerald Durrell described this moment, a sort of epiphany, using words that can be applied to what the traveler will see when he reaches Corfu by sea, following this itinerary, and appears at the ferry deck at dawn:

[…] Il mare gonfiava i suoi azzurri e levigati muscoli ondosi mentre fremeva nella luce dell’alba, e la schiuma della nostra scia si allargava delicatamente dietro di noi come la coda di un pavone bianco, tutta scintillante di bollicine. Il cielo era pallido, con qualche pennellata gialla a oriente. Davanti a noi si allungava uno sgorbio di terra color cioccolata, una massa confusa nella nebbia, con una gala di spuma alla base. Era Corfù, e noi aguzzammo gli occhi per distinguere la forma delle sue montagne, per scoprirne le valli, le cime, i burroni e le spiagge, ma non ne vedemmo che i contorni. Poi, tutt’a un tratto, il sole spuntò sull’orizzonte e il cielo prese il colore azzurro smalto dell’occhio della ghiandaia. Le infinite e meticolose curve del mare si incendiarono per un istante, poi si fecero d’un intenso color porpora screziato di verde. La nebbia si alzò in rapidi e flessibili nastri, ed ecco l’isola davanti a noi, le montagne come se dormissero sotto una gualcita coperta scura, macchiata in ogni sua piega dal verde degli ulivi. Lungo la riva le spiagge si arcuavano candide come zanne tra precipiti città di vivide rocce dorate, rosse e bianche. Doppiammo il promontorio, le montagne scomparvero e l’isola si trasformò in un declivio dolce, macchiato dall’argentea e verde iridescenza degli ulivi, interrotta qua e là dal dito ammonitore di un cipresso stagliato contro il cielo. (G. Durrell, La mia famiglia e altri animali)

However, the traveler who chooses to get to Corfu by plane will appreciate the beautiful sight of the arrival on the island as well, as Mario Praz, a famous Anglicist and art critic, described it in the 1930s during a trip to Greece:

Nuvole dai riflessi di piombo strisciano sopra Corfù. I biancastri promontori dell’isola sfilano in basso, a sinistra. Oltre la plumbea nube si scopre un promontorio azzurro nel sole. Giochi d’ombre e di luce sulla bella isola verde, un lembo di sabbie fulve a occidente, sul mare aperto; e infine la città con le sue fortezze, i suoi grigi tetti antichi e i suoi cipressi, e, di fronte alla rada, un’isoletta simile a una distesa pelle di toro. Tra noi e la terraferma passano veli iridescenti; in uno strappo si mostra un quieto laghetto tra i monti.

Ci abbassiamo; il motore tambureggia, l’idrovolante si tuffa sotto ondate di nuvole, tra i monti dell’isola. Per un momento tutto è opaco intorno; poi uno squarcio di turchino intenso, e questa terra che mi lascio alle spalle, con queste isolette che ne sono la fuggente retroguardia, è l’ultimo lembo di suolo greco. Ma non è un saluto da dio che mi viene alle labbra. Perché la Grecia è più grande; noi occidentali la portiamo nell’anima anche sotto le più inospiti latitudini. (M. Praz, Viaggio in Grecia)

Whether we reach Corfu by ferry or plane, it welcomes the traveler with its “case ammucchiate a casaccio, persiane verdi spalancate come ali di mille farfalle” (G. Durrell, La mia famiglia e altri animali)

The town architecture – Lawrence Durrell points out – is Venetian:

The houses above the old port are built up elegantly into slim tiers with narrows alleys and colonnades running between them; red, yellow, pink, umber – a jumble of pastel shades which the moonlight transforms into a dazzling white city built for a wedding cake. (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

The traveler may not remain indifferent to the elegant and colorful Corfu old town: we suggest following its alleys and then stopping at one of the many cafés in the long colonnaded street built by the French to imitate Rue de Rivoli in Paris upon the wide and lush Esplanade square. Also the famous New York writer Henry Miller used to stop at these cafés and pubs: with his friend Lawrence Durrell, he spent long nights there “seduto a bere qualcosa che non hai voglia di bere” (H. Miller, Il Colosso di Marussi).

Among the old town alleys, the bell tower of Saint Spyridon Church – the patron saint of Corfu – stands out with its red dome that recalls San Giorgio Church in Venice.

He is a very venerated saint by the Corfiots, who dedicate to him four processions over the year, during which the town is full of faithful or simply curious people: the streets are tinged with the bright colors of the Orthodox monks’ and priests’ clothes and the whole island shines in the light of fireworks. It is not easy to explain the rituals and the Byzantine atmosphere that connotes the devotion to this saint; hence let Gerald Durrell, who wound up in the joyful town on Saint Spyridon day with his strange family, tell us how deeply people venerate the relics kept in the saint’s church.

Young Durrell writes:

La città era più affollata e più chiassosa del solito, ma non avevano alcun sospetto che stesse accadendo qualcosa di speciale […]. Domandai a una vecchia contadina che mi stava accanto che cosa stesse succedendo, e lei mi guardò tutta raggiante d’orgoglio.

«È Santo Spiridone, kyria» mi spiegò. «Oggi possiamo entrare in chiesa a baciargli i piedi». Santo Spiridione era il patrono dell’isola. Il suo corpo mummificato era chiuso in una bara d’argento nella chiesa […]. Era un santo molto potente e in grado di esaudire le preghiere, di curare le malattie e di fare per la gente un mucchio di altre cose prodigiose, se uno aveva la fortuna di trovarlo nello stato d’animo giusto quando gliele chiedeva. Gli isolani lo venerano, e metà degli abitanti maschi dell’isola si chiamano Spiro in suo onore. Quel giorno era un giorno speciale, evidentemente avrebbero aperto la bara e consentito ai fedeli di baciare i piedi della mummia, chiusi nelle loro babbucce, e di chiedere al santo tutto ciò che volevano. La varietà della folla dimostrava quanto i Corfioti amassero il loro santo […]. Questo cupo e multicolore cuneo di umanità si muoveva lentamente verso la porta oscura della chiesa, e noi fummo sospinti avanti, travolti come una colata di lava. […] L’interno era buio come un pozzo, illuminato soltanto da una serie di candele che baluginavano come crochi gialli lungo la parete. Un prete barbuto, con l’alto cappello e le vesti nere, aleggiava come un corvo nella penombra, facendo disporre la folla in una sola fila che attraversava la chiesa, passava davanti alla grande bara d’argento e usciva in strada da un’altra porta. […] Non appena raggiungeva la bara, ognuno si chinava, baciava i piedi e mormorava una preghiera, mentre in cima al sarcofago la faccia nera e disseccata del santo spiava attraverso un pannello di vetro con un’espressione di profondo disgusto. Era sempre più chiaro che, lo volessimo o no, avremmo baciato i piedi di Santo Spiridione. (G. Durrell, La mia famiglia e altri animali)

Blessed by Saint Spyridon we may continue our itinerary to discover the island that writers and poets loved so much.

Lawrence Durrell writes:

Corcyra is all Venetian blue and gold – and utterly spoilt by the sun. […] The southern valleys are painted out boldly in heavy brush-strokes of yellow and red while the Judas trees punctuate the roads with their dusty purple explosions. Everywhere you go you can lie down on grass; and even the bare northern reaches of the island are rich in olives and mineral springs. (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

Surrounded with this landscape, we may travel along the south coast, following the route that connects Perama to the nice village of Benitses. Here, in a panoramic area, only 4 kilometers from Corfu town, we can find the villa where the Durrell family stayed at the beginning when they arrived in Greece from England in 1935. The house, which Gerald Durrell called “la villa color rosa fragola” (The Strawberry Pink Villa) in his novel, can be now rented on Airbnb by the traveler, although it does not retain much of its original appearance.

The surrounding landscape preserves much of the charm described by Gerald Durrell:

La collina e le valli tutt’intorno erano un piumino di uliveti che balenavano come pesci guizzanti nei punti dove la brezza sfiorava le foglie. A metà pendio, protetta da un gruppo di cipressi alti e sottili, era annidata una piccola villa color rosa fragola, come un frutto esotico che ammicchi tra il verde. I cipressi ondeggiavano gentilmente nella brezza, come se per il nostro arrivo fossero intenti a dipingere il cielo di un azzurro ancora più vivido. (G. Durrell, La mia famiglia e altri animali)

Benitses area is also famous for its beautiful sandy and pebble beaches; we suggest the traveler enter the clearings and copses of the hills that slope gently down into the sea, in search of some bays or natural inlets, as young Gerald used to do with his faithful dog Roger:

Un pomeriggio, in una calura languida in cui sembrava che tutto dormisse all’infuori delle cicale, Roger e io ci incamminammo per vedere fin dove riuscivamo ad arrampicarci sulle colline prima che facesse buio. Attraversammo gli uliveti, striati e chiazzati di un sole abbagliante, dove l’aria era afosa e immobile, e finalmente, usciti dai boschi, ci inerpicammo su un nudo picco roccioso dove ci sedemmo a riposare. L’isola sonnecchiava sotto di noi, scintillante come un acquerello appena dipinto, nella foschia dell’afa: ulivi grigioverdi, cipressi neri, rocce multicolori lungo la costa, e il mare levigato e opalescente d’un azzurro martin pescatore, verde giada, con qualche lieve increspatura sulla sua superficie liscia dove si incurva intorno a un promontorio roccioso e fitto di ulivi. Proprio sotto di noi c’era una piccola baia lunata col suo bordo di sabbia bianca, una baia così bassa e con fondo di sabbia così abbagliante che l’acqua era di un azzurro pallido, quasi bianco. (G. Durrell, La mia famiglia e altri animali)

Near Benitses, on a hill overlooking the landscape, the traveler may visit Achilleion, a neoclassical-and Pompeian-style palace, where Empress Elisabeth of Austria, better known as Sisi, and later also German Kaiser Wilhelm II enjoyed staying. The writer Henry Miller did not like this site at all, although it is still appreciated by many tourists. He captured perfectly its decadent and showy atmosphere and wrote:

Corfù è un tipico luogo di esilio. Il kaiser soggiornava qui prima di perdere la corona. Una volta feci il giro del palazzo per vedere com’era. A me tutti i palazzi sembrano una lugubre tetraggine, ma questo manicomaniale del Kaiser era la peggior cianfrusaglia su cui mi sia mai capitato di posare gli occhi. Sarebbe un ottimo museo di arte surrealista. (H. Miller, Il Colosso di Marussi)

We do not know if the traveler visiting Achilleion will share Miller’s view, but we are sure that, as the American novelist, he will be impressed by the view on Kanoni bay, enjoyed from its terraces and gardens. Miller writes: “[…] di fronte al palazzo abbandonato c’è una località chiamata Kanoni, da dove si ha la veduta sulla magica Toten Insel”.

The Toten Insel mentioned by Miller is Pontikonisi island, which many scholars consider as the subject of the famous painting by the Symbolist artist Böcklin, Die Toteninsel, that is Isle of the Dead.

This place, definitely evocative, is just a high cliff overlooking the sea, surrounded with a small cypress wood, which can be accessed by boat from the port where the white Vlacherna Monastery rises. From a distance, the monastery as well seems an island surrounded by the sea. The Greeks, less romantically, call Pontikonisi Mouse Island and, according to an enduring tradition, it is one of the sites mentioned in the Odyssey.

Lawrence Durrell gives more details on this legend:

In the dazzle of the bay stands Mouse Island whose romance of line and form (white monastery, monks, cypresses) defies paint and lens, as well as the feebler word. This petrified rock is the boat, they say, turned to stone as a punishment for taking Ulysses home. (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

Most of Corfu charm we would like to show the traveler during this itinerary is linked in various ways to the Homeric echoes of many island sites, not only Pontikonisi, which would be the ship Neptune turned into a rock in the Odyssey, as Durrell had said. Let the British writer introduce us to this legendary sites:

In this landscape observed objects still retain a kind of mythological form – so that through chronologically we are separated from Ulysses by hundreds of years in time, yet we dwell in his shadow. […] the archeologist come and go, each with his pocket Odyssey and his lack of modern Greek. (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

Corfu has always been identified with Homeric Scheria, the island of the Phaeacians, where “l’eroe dal multiforme ingegno” landed after leaving Ogygia and the nymph Calypso. In Odyssey VI, Odysseus is said to have been shipwrecked off the island coasts where he met the beautiful Nausicaa, who was playing ball on the shore with her maids. The nice princess took the hero to the court of her father, Alcinous, the King of the Phaeacians. “A sud della città di Corfù, – Durrell writes – la penisola di Paleopolis dovrebbe essere il sito dove sorgeva l’antica città; ma non è rimasto nulla dei portici, delle fontane e delle colonne della favolosa capitale”. (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

“South of Corfu town, the peninsula of Paleopolis is supposed to be the site of the ancient town; but there is nothing left of the arcades and the fountains and columns of the fabulous capital”. (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

The writer proceeds:

Three towns contend for Ulysses and Nausicaa; Kassopi in the north, with is gigantic plane-tree and good harbour, its bluff ilex-grown fortress where the goats graze all day, might have well been a site for such a fantasy”, the above-mentioned Mouse Island, and “Last and most likely is Paleocastrizza, drenched in the silver of olives on the north-western coast. The little bay lies in a trance, drugged with its own extraordinary perfection – a conspiracy of light, air, blue sea, and cypresses” (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

We suggest the traveler reach these magical places in the island: firstly, Kassiopi, which is still a pleasant fishing village in the northern part of Corfu island.

The origins of this town date back to Roman times and due to its location in a bay protected from the Corfu channel streams, it was a popular harbor among the sailors of the past and Medieval pilgrims headed east. Many legends and stories are told on Kassiopi, not only linked to Odysseus and Nausicaa. Medieval travel journals tell that on that site there was once a strong town, destroyed by the deadly exhalations of a dragon that raged against the people, formerly committed to sodomy. Sailors and pilgrims, when they took shelter in the bay, used to pray in a small chapel dedicated to the Virgin, which was always lit up by a lamp. The lamp was said to exude a miraculous oil able to cure any fever. Overtime it was said that this chapel hosted also a miraculous icon, known as Virgin Kassopitra, painted by Luke the Evangelist.

The chapel, so renowned in the past, can be still visited, although there is little left of its original appearance, since it was seriously damaged during the 16th century due to the Berber raids. The devotion to the small church was so deep that it was promptly rebuilt by the Venetians in 1590. The icon deemed miraculous can be only remembered, but the traveler may guess its form thanks to a 17th-century copy that reproduces it and has become an appreciated object of devotion.

The remains of a castle, probably Byzantine, overlook Kassiopi bay giving the place a romantic and picturesque air. From the main road of the village a road starts and winds up to a hill: on top, the traveler may visit this fortress partly covered with plants, which has been an important Norman, Angevin and Venetian citadel over the centuries.

Also Lawrence Durrell was enchanted by this site and wrote:

Kassopi among the other candidates, has a style entirely its own. […]. The village finds its axis in a giant tree whose shadow falls equally upon the tavern and the church. A good harbour, Kassiopi is the port of call for the carbide fishers, and under the ancient fortress the waves shatter themselves upon ledges of clean granite and arcs of dazzling pebbles. Empty beaches to the north and south stun you by their silence and emptiness, and the egg-like perfection of pebbles. Here and there, in patches of sand, you may see the weird ideograms left by the feet of herring-gulls, the only visitors.

Visitors from Rome came here in the past for summers of indolence and solitude. […] and here the mad flabby Nero (who had translated himself from a weak human being into a symbol of kingship and all its evils) sang and danced horribly at the ancient altar to Zeus. […] (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

Durrell gives us a last suggestion:

“Kassopi must be seen on a festival day”, when it is possible to see the folkloric dances of women, dressed in traditional clothes, who tread hypnotically in a circle and whose songs mingle with the sound of the bagpipes and fiddles or the drum beat.

Now we may move from Kassiopi towards Palaiokatritsa, on the west side of the island, one of the most beautiful sites in Corfu.

Besides its beautiful beaches and the view from the hills over the two Corfu seas, the Adriatic and the Ionian Seas, the traveler may visit the old monastery, which dates back to the 13th century but was extensively restored in the following centuries. Located on a steep promontory connected to the island by means of a thin strip of land, it is the Monastery of Palaiokastrìtsa, whose name means “Quella (la madre di Dio dell’antico castello” (…), with reference to the old Byzantine kastron nearby: the Angelokastron, the most western fortress in the island.

The monastery is a group of small old buildings, close to each other and covered with white plaster. A small courtyard opens inside and leads to the church, which hosts an iconostasis rich in valuable Byzantine icons.

We would like to end this itinerary in the wonderful Kalami village, located in a scenic bay overlooking Albania not far from Palaiokastritsa. In Kalami we can find the house where Lawrence Durrell received his friend Henry Miller.

Now the villa called «The White House» is home to a romantic restaurant by the sea, and it is possible to rent a room on the upper floor. In 1937 the British writer described it as follows:

It is April and we have taken an old fisherman’s house in the extreme north of the island –Kalamai – Ten sea miles from the town, and some thirty kilometres by road, it offers all the charms of seclusion. A white house set like dice on a rock already venerable with the scars of wind and water. The hill runs clear up into the sky behind it, so that the cypresses and olives overhang this room in which I sit and write. We are upon a bare promontory with its beautiful clean surface of metamorphic stone covered in olive and ilex: in the shape of a mons pubis. This is become our unregretted home. A world. Corcyra.

[…] White house, white rock, friends, and a narrow style of loving: and perhaps a book which will grow out of these scraps, as from the rubbish of these old Venetian tombs the cypress cracks the slabs at last and rises up fresh and green. (L. Durrell, Prospero’s Cell. A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra)

Miller was definitely one of the friends who enlivened Durrell’s white house in Kalami; he came here, persuaded by his friend Lawrence, as he tells us:

Ricevevo dalla Grecia lettere del mio amico Lawrence Durrell, che di Corfù aveva praticamente fatto casa. Anche le sue lettere erano meravigliose, ma per me un po’ irreali. Durrell è un poeta e le sue lettere erano poetiche: producevano in me una certa confusione, per via che sogno e realtà si mescolavano sapientemente. In seguito avrei scoperto che questa confusione è reale e non tutta dovuta alla facoltà poetica. Ma allora pensavo che egli caricasse le tinte, che questo fosse un modo di indurmi ad accettare i suoi ripetuti inviti ad andarlo a trovare. […]

Pensavo, quando questi messaggi araldici arrivavano a Villa Seurat in una fredda giornata estiva parigina, che egli si fosse fatto di coca prima di ungere la penna. (H. Miller, Il Colosso di Marussi)

Durrell’s letters had the desired effect and, in 1939, a few months before the Second World War, Miller reached his friend in Corfu. That trip, which took the writer also to other Greek sites, gave birth to one of his best books, The Colossus of Maroussi. It has accompanied us throughout some steps of this itinerary, which ends here in the nice Kalami. We would like to say goodbye to the traveler, by sharing the American writer’s thoughts and hopes expressed at the end of his travel book. Miller writes:

Quando parlo dell’effetto che questo viaggio in Grecia ha prodotto su di me la gente sembra stupefatta e ammaliata. Dicono di invidiarmi, si augurano di poterci andare un giorno anche loro. Perché non lo fanno? Perché nessuno può godere l’esperienza che desidera finché non è pronto ad accoglierla […] La luce della Grecia mi ha aperto gli occhi, mi è penetrata nei pori, ha ampliato tutto il mio essere. […]. Pace a tutti gli uomini, dico, e vita più copiosa! (H. Miller, Il Colosso di Marussi)