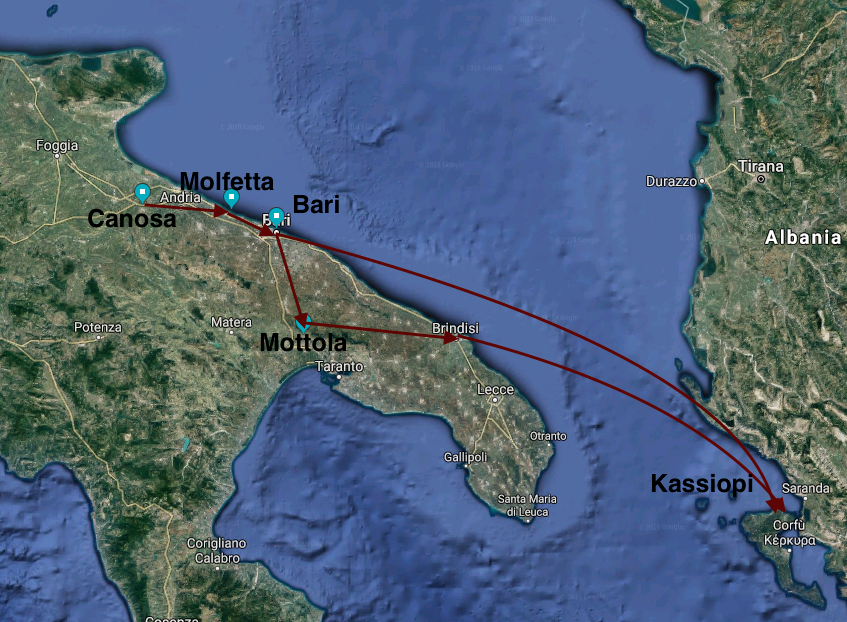

Canosa, Molfetta, Bari, Mottola, Corfu, Kassiopi

Itinerary – The Pilgrim’s Tales

In this itinerary the traveler is invited to ideally hold the pilgrim’s staff or, more secularly, to become a wayfarer, in order to go along the Apulian stretch of the road known as Via Francigena in the South or Via Sacra Longobardorum, rich in history, art and culture. Following the route of an old Roman consular road never completely abandoned, the Via Appia-Traiana, we will get to the region’s port towns, which have always been key embarkation points for pilgrims, Crusaders, Templars or merchants who wanted to reach the fabulous East over the Middle Ages. Following in their footsteps and guided by their stories and travel journals, we will finally head for the Ionian Islands, a nearly necessary step for people who once sailed towards or from the Holy Land or the rich eastern markets.

The itineraries that led from the West to overseas lands, in particular to Jerusalem, have created material, spiritual and cultural paths over time, a system of waterways and overland routes that crossed Europe and the Mediterranean, at the center of which there are just Puglia and the Ionian Islands, with their docks and holy sites.

The itinerary we are about to follow along the southern stretch of the Via Francigena is not only a journey of faith, but one of the main routes of Mediterranean culture; following it, we can discover how nature, history and artistic heritage contribute to make our journey not a single journey, but many, as the polished traveler, literary man and art historian Cesare Brandi wrote. Together with the pilgrims of the past, he will guide us to discover these lands.

We suggest the traveler start his journey in spring, as Medieval pilgrims did:

G. Chaucer’s portrait as a pilgrim, 15th century

Quando pioggia d’aprile ha penetrata

l’aridità di marzo e impregnata

ogni radice e vena dell’umore

la cui virtù ravviva ogni foglia e fiore;

e in folto di brughiere e boschi spogli

Zeffiro ingemma teneri germogli

con mite soffio, e metà del corso

il sole nell’Ariete ha già percorso,

e quando gli uccelletti fan concerto

e tengono di notte l’occhio aperto,

così com’essi loro natura inclina,

[…] allor la gente viaggia pellegrina

e vanno a santuari, quei palmieri, in lidi anche remoti e forestieri […]

Geoffrey Chaucer, I racconti di Canterbury, Prologo

Puglia, a long strip of land nestled between the Apennines and the Adriatic Sea, with its 400 km of lands alternating extraordinarily diversified landscapes and architecture and 800 km of swimming coastline, is crossed by a network of roads that intersect the main Via Francigena’s route.

Our itinerary will start going along one of these roads, that leading travelers from Canosa to the Adriatic coastal road. We will reach the coast and stop off in Molfetta to proceed to Bari, a town known for Saint Nicholas’ sanctuary. Finally, before sailing for Greece, we will make a small detour, as Medieval pilgrims did when they got to the Apulian coast through the Via per compendium, which connected Taranto to Brindisi. This route, reported in the oldest itineraries, will allow us to visit the rock sanctuaries located along the ravines that connote this area.

Ancient pilgrims and modern travelers are impressed by the natural beauty of this land, more than by its artistic heritage and monuments; Cesare Brandi, during his pilgrimage in Puglia, describes it as follows:

La Puglia è un meraviglioso, austero, paese arcaico. L’unico dove si assiste ancora allo spettacolo incontaminato, e per interminabili distese, di una flora anteriore alla calata degli indeuropei: solo ulivi e viti, viti e ulivi, le piante che nel nome, tenacemente conservato e trasmesso, rivelano ancora di essere state trovate sul posto dagli invasori ariani (C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia).

As the 20th-century polished wayfarer, many Medieval pilgrims praised the Apulian landscape. Two educated Flemish noblemen, Giovanni and Anselmo Adorno, who landed in this region in the 15th century coming back from the Holy Land, wrote in their fascinating travel journal that they had never seen such a fertile land or such beautiful olive groves:

La Puglia o Apulia […] credo che sia la più fertile al mondo per la produzione di olio e di grano. Produce in abbondanza anche dell’eccellente vino, […] ci sono boschi di ulivi, che è piacevole attraversare. È possibile altrove, come in Siria, in Barberia, vedere boschi di ulivi, tuttavia questi ci sono sembrati più piacevoli a guardarli e più grandi. (A. Adorno, Itinéraire d’Anselme Adorno en Terre Sainte)

The green of olive trees and vines and the gold of wheat will accompany us in our journey along the road that, between the end of the 11th century and the beginning of the 12th century, will become the preferred itinerary not only by pilgrims, but also by the Crusaders who had to sail for the Holy Land. One of these Crusaders was Prince Bohemond, who sincerely loved Puglia, in particular Canosa, the first stop of our itinerary.

An important town in Roman times, thanks to its proximity to the river Ofanto and its strategic location at the intersection between the roads coming from the Apennines and Puglia, it became the heart of Norman power and the seat of a prestigious diocese. Just in this town we can visit the mausoleum – whose shapes are inspired by the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem and Islamic architecture – commissioned by Bohemond next to the Cathedral (The Cathedral of Canosa).

The Norman prince, son of Robert Guiscard, had participated in the occupation of Antioch becoming its ruler and spent an adventurous life, rich in love, kidnappings and conquests that made him stay in the East for many years before returning to Puglia.

(“File:Paolo Monti – Servizio fotografico (Canosa di Puglia, 1970) – BEIC 6358124.jpg” by Federico Leva (BEIC) is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Cesare Brandi, whose literary and artistic pilgrimage stopped off in Canosa, may tell us something more about the prince and guide us to know this unusual 12th-century monument with marble walls that are externally decorated with a light succession of blind arches. Rather than a funeral monument, it seems a precious casket or reliquary, as those the pilgrims took back home from the East.

Come s’arriva là davanti, e sembra un cofanetto d’avorio, si penserebbe piuttosto alla cappella privata o alla tomba di una possente gentildonna sul tipo di Galla Placidia o a un marabutto arabo, mai al ricettacolo del più straordinario personaggio della Prima Crociata, a quel colosso di nome e di fatto che fu Boemondo, il figlio di Roberto il Guiscardo. Orlando fra i Paladini, e, nella Prima Crociata, Goffredo di Buglione e Tancredi, sono riusciti a sopravvivere per merito della Poesia. A Boemondo che, al suo tempo, fu di tutti il più famoso, non è toccata uguale sorte […] Boemondo è mezzo eroe e mezzo farabutto, e come farabutto riesce ad innalzarsi fino all’eroe: resta sempre il figlio di quella malaugurata razza di avventurieri senza un soldo a cui aveva appartenuto suo padre. Se la leggenda o la poesia l’avessero passato al filtro, a quest’ora, il bello scrigno marmoreo sarebbe famoso al mondo, e il nome di Canosa suonerebbe almeno come quello di Roncisvalle […]. Orlando sembra d’averlo conosciuto come una persona morta presto e di cui tutti in famiglia dicevano bene, con Tancredi siamo andati a scuola[…]; questo Boemondo, cinico, traditore, insaziabile, ma nato capo con i capelli biondi, Boemondo non si arriva a vederlo. (C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia)

The traveler may visit the evocative small temple that keeps Bohemond’s remains according to legend; he may admire the beautiful double-leaf bronze door adorned with Islamic decorative motifs. On the left side, we may read part of an inscription celebrating the crusade prince: non hominem possum dicere, nolo deum. (I can neither call him man, nor God.)

Leave Bohemond and Canosa behind and proceed to Molfetta, which, as other Apulian coastal towns, was an important bridge between the East and West when its wide port became the landing place of crusade sailing ships and Venetian galleys, now replaced by a lively and colored fishing boat fleet that enlivens its life.

The Adriatic town is reflected in the Adriatic Sea of this picturesque port, with its walls:

vecchie mura che ancora cingono, ammansite e utilizzate a case, sopra a cui scorre una strada anulare, la città vecchia, minuscola e complicatissima città. Ancora più che a un labirinto o a un meandro, fa pensare d’essere entrati in una serratura: né solo per quella porta che può simulare il foro della chiave. Le straducole strettissime e alte seguono un itinerario proprio, e non hanno mai un punto d’arrivo preciso, una piazza, una chiesa. Si direbbe, se quelle ci sono, che la costeggiano, vi arrivano per la tangente: cunicoli scavati nella pietra tenera e chiara su cui arrivano i riflessi del mare. (C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia)

The pilgrims arriving here in the Middle Ages had two important devotional landmarks, which will become also the stages of our itinerary: the cathedral and the sanctuary of Madonna dei Martiri.

The Cathedral of San Corrado (The Cathedral Of Molfetta) stands out between the blue of the Adriatic Sea and the sky, along the Medieval walls and overlooking the sea. The saint, the dedicatee of the beautiful church in Molfetta, was a noble German pilgrim who had arrived in town from the Holy Land. His relics and the renown of his miracles increased both the flow of travelers seeking grace and Molfetta’s fame. Brandi writes:

[…] impossibile evitare il tono solenne per questo solennissimo monumento tagliato nella pietra a spigoli vivi come una pietra preziosa, estratto dall’Armenia si direbbe, e posato sulla sponda di un porticciolo vero e attivo, pieno di barche e bragozzi, che si carica e si scarica di pesce alle sue ore. […] I riflessi del mare (ndr) danzanti e capricciosi, rappresentano il fascino saltuario, ma indimenticabile della Cattedrale, a cui le varie fasi costruttive non riescono a incrinare una monumentalità così imponente e diretta da sembrare raggiunta tutta in una volta. E non lo è, perché le fasi restano indubbie, e i successivi colpi di timone: ma quale intelligenza, quale prescienza nel ricucire le parti diverse. Le tre cupole non sono meno splendide all’interno, quando il rivestimento prismatico, con angoli così aguzzi, le fa parere tende tartariche issate sul tetto della Cattedrale. Dopo San marco a Venezia, è forse la chiesa dagli spazi più misteriosi: quel senso aspirante o da incubatrice che hanno le tre cupole, la cui presenza è davvero inscindibile e talmente preparata dalle volte delle navate laterali, a mezza botte, rampanti, che sembrano spalle curve a sostenere il peso superiore o ben piuttosto il volo aereo di un volteggio. Così le cupole si issano scavalcando la chiesa. (C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia)

Once out of the church, the traveler cannot miss the experience of walking in the old town of this Adriatic city:

[…] e si vien presi nelle volute, nei giri viziosi delle viuzze, che sembrano come i fili, ma sempre lo stesso, di un gomitolo, ci si sente consegnati a uno spazio volubile, a un percorso interno alle cose, che mai ci consentirà una libera uscita, o, pur così tangente al mare, una veduta sul mare con borghese panchina. Il percorso diviene allora una segreta dimensione di spazio che non è più nostro: ed è in questo, che lo sviluppo delle vie diviene come un brancolare a mosca cieca. Ma un brancolare luminoso che la pietra tenera e bianca, d’un bianco leggermente livido e rosato, come la pelle di chi sta sempre vestito, restituisce con quel saltellio di luci marine, screziate dalle onde robuste e rovinose che stanno per inghiottirsi, un morso alla volta, questa meravigliosa città vecchia di Molfetta. (C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia)

After passing through the old town, on the other spur that delimits the mouth of the port, we can see the Sanctuary of Madonna dei Martiri with its hospital, where both the Crusaders and the pilgrims heading towards or coming back from the Holy Land were hosted and cured. Following the First Crusade, the South of Italy housed a number of hospitals – facilities used for the pilgrims’ rest – managed by Knights Hospitaller, Templars and Teutonic Knights.

The Molfetta sanctuary was erected in 1162 and, shortly after, the hospital was also built (The Ospedale Dei Crociati (Crusaders’ Hospital)). It was one of the few that remained almost intact. The traveler may still see its longitudinal plan structure, divided into three naves of the same-height by means of strong cruciform piers. The building has parallel barrel vaults, marked by transverse round arches. The area is lighted up by a series of single-lancet windows facing the sea.

Once left the Ospedale dei crociati (Crusaders’ Hospital), as the wayfarers of the past, we suggest visiting the Molfetta sanctuary of Madonna dei Martiri, where we can still admire the icon, considered miraculous and thaumaturgic, which according to legend came from the Holy Land, rescued by the Crusaders in 1188, in the aftermath of the fall of Jerusalem. It is the icon of Madonna dei Martiri (Our lady of the Martyrs), a considerably repainted board that represents the iconographic type of the tender Virgin: its dating is uncertain, but it was probably made in the 14th century.

(Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61405024)

Pilgrims, always in search of a divine sign, could not remain indifferent to this place, therefore Molfetta, from being just a stage, became a place of pilgrimage in a short time. The renown of its sanctuary was connected to that of the icon as a miraculous object.

In his travel journal, the pilgrim Anselmo Adorno goes into a detailed description of the miracles made by the worshipped icon:

La Chiesa Nostra Signora dei Martiri è situata ad un miglio da Molfetta sul mare; è grande e frequentato luogo di culto. Sono sepolti numerosi corpi di martiri: perciò è chiamata Nostra Signora dei Martiri. Si trova isolata sul litorale con alcune case di pertinenza della medesima chiesa. I preti che amministrano la chiesa abitano nelle case vicine e danno accoglienza ai pellegrini in caso di bisogno. In essa c’è l’immagine di Nostra Signora, che compie molti miracoli, così come leggiamo in chiesa. Stando all’interno abbiamo ascoltato un prete di Barletta raccontare uno dei grandi miracoli compiuti sulla nave dove si trovava.

Questa nave era andata dispersa nella tempesta. Spinti dal padrone che promise la metà del suo bastimento a Nostra Signora dei Martiri, coloro che si trovavano a bordo e che speravano di salvarsi fecero un voto alla Vergine. Compiuto il voto, la Vergine apparve loro sulla prua della nave. Apparve anche un giudeo coperto di lebbra, che si mise ad adorarla, che chiedeva di essere liberato dalla malattia e dal pericolo del mare e si dichiarò subito cristiano. E grazie a tutto questo la nave giunse nel porto di Corfù. La Beata Vergine fece in questo luogo altri miracoli. Per questo motivo annualmente confluiscono molti pellegrini.

(A. Adorno, Itinéraire d’Anselme Adorno en Terre Sainte)

In the 15th century, the sanctuary was very popular among pilgrims and, today as in the past, in such a crowded place one could be victim of petty or serious thefts, as Fra’ Mariano da Siena tells in 1431, coming back from his pilgrimage in the Holy Land and passing through Molfetta.

[…] e venimo a rinfrescarci a Morfetto.[…]

e visitammo S. Maria de’ Martiri , e mentre che noi eravamo in Chiesa , fu tolta la tasca con molte coselline, che valevano parecchi fiorini , a uno de’ nostri compagni . Questa Chiesa è cosa

di grande devozione […] (Mariano da Siena, Del viaggio in Terra Santa fatto e descritto da ser Mariano da Siena nel secolo XV)

Let’s leave Molfetta and, going forward along the Adriatic coastal road, head for Bari, considered by Medieval pilgrims not as a mere stage of their hard journey, but mainly the town that houses one of the most popular sanctuaries of Medieval Christianity. It is the Basilica di San Nicola (Basilica of Saint Nicholas), a church that assumes immense importance in the history of Bari’s civic identity. Although it is not the town cathedral but a pilgrimage church, it is definitely the dearest sacred building to Bari people and the most frequented building by pilgrims over the centuries.

Hence, the journey of the pilgrims arrived in Bari leads to the Basilica that keeps the remains of the saint who came from the sea. This place became the ideal intersection between the major waterways and overland routes leading to or coming from Jerusalem and Saint James of Compostella, the ultimate destinations of Medieval pilgrimage main routes.

Today’s and yesterday’s wayfarers may reach it only after entering the old town urban fabric.

Cesare Brandi writes:

Quasi a picco sul mare […]. Dal mare viene la sua vita e la sua morte, i commerci e le flotte piratesche dei Saraceni. Da questa apertura che deve essere al tempo stesso chiusura nasce il carattere asserragliato della città vecchia, le strade come cunicoli e le ampie oscure volte che le scavalcano. […]. Sembra che, prima delle strade, sia stata fatta una costruzione tutta di massello, e poi forata da strani, industri litofagi. […]. Bari vecchia è l’aggregato arabo, e quando non è Gerusalemme, è Damasco: le volte hanno il senso del mercato coperto, che sia Bazar o Suk. E sono anche le volte di un paese che vuole deviare e rompere i venti gelidi che vengono da Settentrione, e ripararsi dal sole che, d’estate, ossia otto mesi l’anno, calcina gli occhi e le pietre. (C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia)

In this maze of streets, after running along the castle (The Castello Svevo (Norman-Swabian Castle)) and the cathedral (The Cathedral Of Bari), and having followed the present Via delle Crociate, we get to Via Palazzo di città, once called Ruga Francigena, namely Francigena way. This road, which crosses the old town and finally leads to the square of the Basilica di San Nicola (The Basilica Di San Nicola (Basilica Of Saint Nicholas)), in its name, reminds us that we are following exactly the stretch of the old European pilgrimage route that ran through Bari, in order to allow the pilgrims to visit Saint Nicholas’ sanctuary, worship his relics, and get blessing to continue the rest of their journey safely.

The pilgrims of the past, along with us, often tried to make their arrival in Bari coincide with the day dedicated to the patron saint, namely 8 May. Through their writings, we may evocatively travel backwards in time to discover habits and customs of this religious and popular festival that still attracts pilgrims and tourists.

This journey backwards in the devotional imagination starts in the Basilica crypt, accessed through a staircase in the aisle which leads the faithful to an Oriental and Byzantine mystical dimension, thanks to the abundance of icons, lamps, precious metal ornaments, fabrics and embroideries that contribute to make the view of Saint Nicholas’ relics – here kept – extremely evocative. Anselmo Adorno describes them in his journal:

Le spoglie riposano in un’arca di marmo sotto il grande altare della cripta. La parte anteriore dell’altare è istoriata con immagini sbalzate in argento. Sempre sul fronte dell’altare c’è una porticina attraverso cui, da un foro che penetra all’interno del monumento, ove una lampada accesa pende da una catena d’argento, si distinguono le reliquie di S. Nicola. Da esse dicono che scaturisca un olio santo, ovvero un liquido con cui vengono unti occhi e fronti delle persone nelle festività solenni, così come fu nel tempo in cui noi fummo a Bari, cioè nel giorno di S. Nicola.

(A. Adorno, Itinéraire d’Anselme Adorno en Terre Sainte)

Many pilgrims of the past visited the sanctuary to get a miraculous liquid, called manna, that was said to exude from the saint’s body.

Continuous flows of pilgrims, coming from both the East and West, have kept on crowding the tomb of the Bari saint over the centuries, as Emile Bertaux writes at the end of the nineteenth century:

[…] sin dai primi giorni di maggio, la città vecchia, che con i suoi vicoli tortuosi stringe le mura della basilica fortificata dai re angioini, si agita e trabocca. I visitatori hanno preso d’assalto la chiesa; si sono stabiliti nelle navate laterali e persino nelle cappelle; sono lì accampati, dormono, mangiano. […] Così scendono fin giù nella cripta, con la testa che batte sugli scalini, e quando si rialzano vacillanti, vedono al di sopra della buia folla, tra le colonne annerite, la volta rivestita d’argento, tutta rutilante di luci, e il massiccio altare d’argento, dove il corpo di San Nicola, nell’ombra, stilla una miracolosa manna. […]. È necessario che ogni famiglia porti via la sua bottiglia piena del misterioso liquido che stilla dalle ossa di San Nicola come da fonte inesauribile. (E. Bertaux, Sur les chemins des pèlerins et des émigrantes, 1897)

The town still dresses up for three days, 7, 8 and 9 May, and commits entirely to the saint’s celebrations, between the sacred and the profane. We suggest the traveler who arrived here through this itinerary ideally join the festival and plan his trip so as to enter the joyful atmosphere that pervades Bari during Saint Nicholas’ days, as the ‘Apulian pilgrim’ Cesare Brandi did. He introduces us into the merry and chaotic folk dimension that prevails in the town with his words:

[…] per i festosi viali di Bari, archi di lampadine a non finire, che rientravano l’uno nell’altro, come cerchi concentrici di un tiro a segno. La strada, fitta di popolo a contatto di gomito – e del resto – sembrava ridotta a un palcoscenico in lieve pendenza. […]

Gli archi luminosi non erano le sole luci, sotto le stelle compiacenti, della vigilia della festa: non potevano mancare i fuochi, quest’altro costoso lusso del Meridione, dei poveri che si danno allo scialo. E in quanto allo scialo, per San Nicola, i Baresi si sprecano. […] Si comincia, appunto, dalla sera della vigilia, quando una tremolante caravella a ruote, fra nubi di fumo e modeste crepitanti torce di fuoco greco, con un’immagine di San Nicola a bordo e alcuni vecchietti in costume da Cena delle beffe, passa tra la folla della città fino a trascorrere sotto gli archi luminosi. Questa rievocazione del famigerato furto perpetrato dai Baresi a Mira, in gara nobilissima coi Veneziani, è dunque una specie di Sacra Rappresentazione, senza preti e senza canti, dove la voce è messa solo dai botti dei fuochi d’artificio, […]. (C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia)

(just_jeanette is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

(daromeo76 is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0 )

The celebrations will continue on the following day, 8 May: «quando – writes Brandi – il Santo va in mare, sotto un sole, che, se anche è maggio, è già piena estate, in un cielo che è chiaro come in Africa» on a fishing boat, which recalls the link between the town and the sea and the arrival, by the same sea, of Saint Nicholas’ relics, smuggled in the 11th century in Myra (Turkey) by a group of sailors from Bari.

Brandi says:

Il Santo va in mare, vestito, sulla statua d’argento, di paramenti d’oro e circondato, invece che da torce e flabelli, da mazzi di fiori nuziali – garofani bianchi e calle – montati su lunghe aste d’argento, come quelle che reggono i baldacchini. Il Vescovo in persona, che comanda la processione, getta allora un’ampolla con la manna di San Nicola. […] Il mare, allora, questo eterno ricetto materno, la Teti antica e dell’inconscio, alla fecondazione nuziale risponde con l’urlo subitaneo e lacerante, discorde fino a raggiungere il più implacabile salasso elettrico, di non so quante sirene, dalle navicelle, dai trabiccoli, dai motopescherecci, raccolti attorno al motopeschereccio del Santo, come le api intorno all’Ape regina. […] Ora la fecondazione è avvenuta, il santo si riposa, la gente dalla terra esulta, perché il patto col mare, la parentela indissolubile, è per il bene della terra. […] Il pubblico straboccante, meravigliosamente nero e rosso, brulicava sul lungomare, fitto come puntini di un quadro di Seurat. Finché il Santo rimane in mare, il brulichio non cesserà. (C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia)

The following day Saint Nicholas’ statue returns to its beautiful Romanesque Basilica: the traveler may decide whether to embark soon, under the saint’s protection, or continue his journey across Puglia for a while, before catching one of the ferries that regularly connect the Apulian county seat to the Greek islands.

Many pilgrims of the past chose to embark from Brindisi, as an alternative, and reached the town of Upper Salento following the route of the Via Appia-Antica; in particular, the stretch of road connecting Taranto to Brindisi was frequently taken all over the Middle Ages.

In the area surrounding this road, it is possible to admire the cave Apulian environment (The Rock Civilization In Puglia): entire hamlets, shrines, and hermitages carved out of rock will guide the visitor to enter a mystical dimension, connoted by a delicate charm, which is totally different from that of the imposing Romanesque basilicas we left along the coast. A dense network of roads winds between Massafra, Mottola and Gravina, where the pilgrim’s route meets the ancient transhumance path.

Our literary guide, Cesare Brandi, looking for rock crypts – as we do – reaches Mottola, a town in the province of Taranto, located as he says:

su un’altura che non è un’altura, ma per le Puglie lo diventa: e si vede di lassù uno dei paesi più armoniosi che vi siano, con in fondo il mare. Armoniosa è infatti la discesa degli ulivi corvini, densi come gomitoli, nel pullulare del primo verde delle viti […] armoniosi grani fitti, arditi, rigidissimi, come capelli a spazzola, accanto ai ricciuti boccoli di verde opaco e gagliardo delle fave. Non mi stancavo di guardarlo, quel paese, così scoperto e largo e disteso, che il mare quasi pareva appena l’orice di tanta morbida bellezza.

Invece bisognò staccarsi dal panorama e andare in cerca delle cripte. Naturalmente qui ce n’era un visibilio, volendo: ma a me interessava soprattutto quella di San Nicola, e speravo che trovandosi in aperta campagna, bisognasse cercarsela a piedi […]. Non fui deluso. A un certo punto si arrivò all’antico convento ridotto ad abbazia, e lì la strada campestre finiva.

(C. Brandi, Pellegrino di Puglia)

The rock church of San Nicola, one of the nicest among the «Mirabili Grotte di Dio» (Charles Diehl), was venerated for centuries not only by the town inhabitants, but also by Crusaders and pilgrims – whose steps we are following in – who reached Taranto and Brindisi to sail for the Holy Land.

The rock church of San Nicola, one of the nicest among the «Mirabili Grotte di Dio» (Charles Diehl), was venerated for centuries not only by the town inhabitants, but also by Crusaders and pilgrims – whose steps we are following in – who reached Taranto and Brindisi to sail for the Holy Land.

The church is on the edge of a small ravine and can be accessed through stairs carved out of rock.

This underground sanctuary has a cruciform plan inscribed in a quadrangular hall, divided into three naves. They are separated only by two massive pillars, according to a structure that could be also found in Syria from the 6th century. The chancel of the church, called bema, isolated from the rest of the interior by means of an iconostasis, is divided into three different cells, each with its own altar. The interior, almost entirely frescoed, has one of the most interesting pictorial cycles in Puglia in terms of quality and preservation, dating back to the period between the 11th and the 13th century. This place has been defined as the Sistine Chapel of the Southern Italy rock civilization.

Our traveler, after this detour, should proceed and head for the Ionian Islands, a nearly necessary step for people who sailed towards the East or the Holy Land in the Middle Ages.

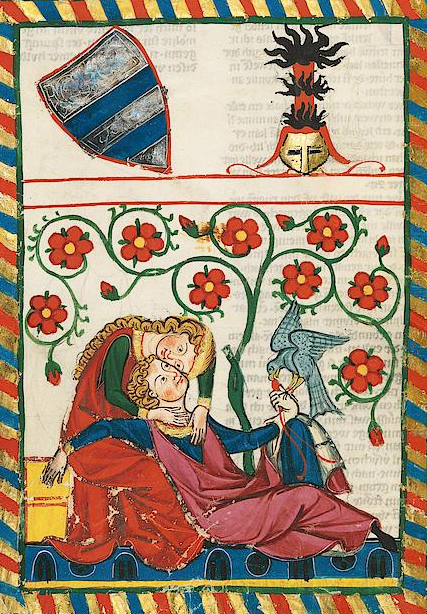

The time of leaving was not pleasant for all travelers, especially for armed pilgrims, namely the Crusaders, who left the safe Apulian coasts. The poet Tannhäuser, an unwilling Crusader of Frederick II’s retinue in 1228, regrets the joy he is leaving behind when abandoning the beautiful land of Puglia in a lyric poem. His verses allow us to go back in time and imagine how enjoyable the life of dames and knights could be in the imperial palaces of the region. In the context of the Apulian landscape, romantic meetings, jousts and hunts gladdened the days of those who might stay, unlike the poet.

Heidelberg, Universitätsbibliothek

Heidelberg, Universitätsbibliothek

Beato colui che ora può cacciare con il falcone sui campi di Puglia! […]

alcuni vanno alle fonti, gli altri cavalcano guardando il paesaggio ‒ questa gioia mi è tolta ‒ quelli caracollano accanto alle dame […]

io non caccio all'arco con i cani, io non uccello con i falconi, […], e nessuno mi può rimproverare di portare corone di rose […]

neanche mi si può attendere dove cresce il verde trifoglio, né cercare nei giardini accanto alle belle giovani […]

io fluttuo sul mare.

(Tannhäuser, in A. Martellotti, Il viaggio controvoglia del crociato Tannhäuser)

Corfu, Kassiopi

(Bejo, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3086242)

Sailing from the Adriatic coast, it is possible to reach Ithaca, Cephalonia and Corfu, where the threatening channel of Butrint, with its dangerous streams, was waiting for those who wanted to continue their journey. When pilgrims or merchants passed through this area, it was advisable for various reasons to stop at the natural shelter of Kassiopi bay, in the northern part of Corfu island.

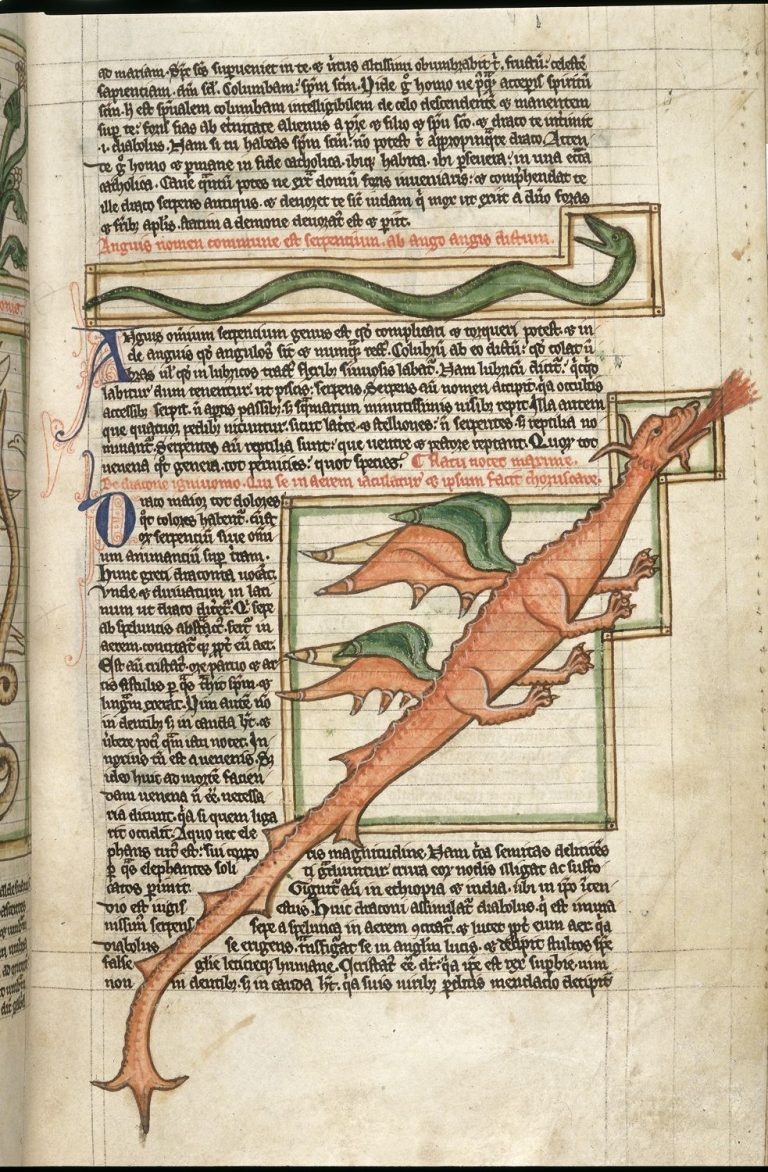

Today the traveler may visit this pleasant fishing village, which dates back to Roman times and may learn its history, discovering its literary imagination described in the pilgrims’ diaries that tell about dragons, magic lamps, hermitages, chapels and miraculous icons, as the one vaguely recalled in the small church of Virgin Kassopitra, who protects sailors and travelers.

Medieval pilgrims tell that Kassiopi was once a strong town, now totally desert due to the deadly exhalations of a dragon that raged against the people, formerly committed to sodomy. Sailors and pilgrims started to regularly frequent a small chapel always lighted up by a lamp. The lamp miraculous oil was said to cure any fever. Overtime it was told that this chapel hosted also a miraculous icon, known as Virgin Kassopitra, portraying the Virgin painted by Luke the Evangelist. (M. Bacci, Portolano sacro. Santuari e immagini sacre lungo le rotte di navigazione del mediterraneo tra tardo medioevo e prima età moderna).

The chapel, so renowned in the past, was seriously damaged during the 16th century, due to the Berber raids, but was promptly rebuilt by the Venetians in 1590. The icon deemed miraculous has now disappeared, but has been replaced by a 17th-century votive icon that reproduces it and is still an object of devotion.

It is also mentioned in the travel journal of Marquess Nicolò d’Este travelling to the Holy Sepulcher, written by his faithful chancellor, Luchino dal Campo.

He wrote:

Et andando il Signore al suo viaggio, la sira andò alla isola di Corfù, in uno porto chiamato Nostra Dona da Casopoli. E qui, gittato ferro e la barcha all’acqua, andò in terra a la giexia di Nostra Donna , ove li è una lampada denanti alla sua figura, la quale sempre arde e sempre sta piena di olio, ní mai se ne mette guzzo di olio; et fu dato de un certo legno bagnato del dicto olio a tucta la compagnia da uno calogiero che sta lì, e disse esser bono de guarir ogni febre. E, visitato questa figura la qual fa miracoli, andorono a vedere uno castello chiamato Casopoli, molto bello ma disabitato per uno serpente il quale habitava lì e avelenava tucto il paexe. (Luchino dal Campo, Viaggio del Marchese Nicolò d’Este al Santo Sepolcro, 1413)

The castle, mentioned by Medieval pilgrims and travelers, can still be visited. From the main road of the village another road starts and winds up to a hill overlooking the bay. On top we can find the ruins of the original Byzantine fortress, surrounded by plants. The castle was conquered in the 11th century by a man we have already met in our itinerary in Canosa, Prince Bohemond. The Norman dominion over Corfu did not last long and the castle was controlled by the Byzantine emperors until the arrival of the Angevins in 1266. Finally, the castle was destroyed by the Venetians in the 14th century, when they took control of the island. Only at the beginning of the 18th century they decided to rebuild the castle in order to limit the Ottoman raids.

Our pilgrimage searching for beauty and discovering Medieval monuments, stories and legends, closely linked to the place identity, ends on this island and on this fortress that allows us to overlook the Strait of Corfu, aware that the end of this journey may become the start of another itinerary or another story.

( Dr.K., CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68635379)