Introduction by R. Nicolì

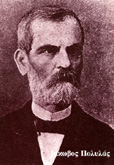

This text, here entirely reproduced for the POLYSEMI Library, is a pamphlet written by the renowned Salento scholar Cosimo De Giorgi, published by the Milan printing house Wilmant in 1872.[1] Originally, it was a letter – dated 10th October 1870 – the author sent to his colleague from Pisa Guido Mugnaini; its content is closely related to the Apulian Project Area, since it concerns a short excursion from Bari to Taranto by train. In the nineteenth century the inclination for local and limited itineraries, after a season of long journeys all over the peninsula, as the Grand Tour required, was new.

The text is a nature, geological and orographic report on the territory, but in some passages it is enriched with elegant descriptions of the writer’s mood and quotations from classical authors that let us remember the ancient splendor of Taranto in Magna Graecia. De Giorgi often seems to use his vast scientific knowledge as an instrument, as it provides him with an objective analysis method, but the writer combines it successfully with the inclination to outline his emotional involvement in the descriptions, offering the reader the best pages of his short text. After all, this aspect is anticipated by the subheading choice, in the etymology of the word Impressioni that recalls the effect and the influence of external reality, with its direct or indirect intervention, on the narrator and traveler’s conscience, feelings and perceptions. De Giorgi anticipates that he will deal with places as well as with his own experience – cognitive or emotional – the journey determines. It is a linguistic choice frequently adopted by the author, who in the same year entitled the account of a journey from the northern edge of Puglia to Campania Da Napoli a Foggia. Impressioni di un viaggio nell’aprile del 1870[2] and seven years later will use the same term in the title of a prose volume on the southern part of Lecce province,[3] Bozzetti e impressioni, clearly aimed at underlining the aesthetic and introspective emotion of travel.

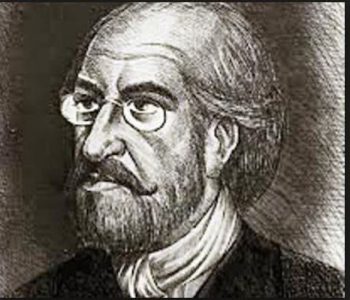

The writer, a native of Lecce province, graduated in Medicine in Pisa following his family tradition, but throughout his life he juxtaposed the medical profession and the teaching profession. The latter was accompanied by an intense research activity that reflected his varied cultural interests and focused on the most diverse disciplines: from geography to archaeology and from agriculture to economics. His studies on the landscape and monument history in Terra d’Otranto are well-known; he also planned demanding and necessary repairs for these monuments.[4] The text that made him famous, not only locally, was Bozzetti di viaggio [5] in two volumes, the possible development of Bozzetti e Impressioni, in which he describes the monuments of the three Salento provinces. It is a sort of artistic, landscape and architectural survey of Terra d’Otranto heritage, which results from critical and evaluative choices.[6]

Within a complex cultural context, heritage was considered as a manifestation of History, and History was perceived as Morals ‘in action’, namely Ethics, in line with Benedetto Croce’s theories. In particular, between the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, Magna Graecia was considered as the cradle of a cultural model in which the notions of Local Identity, Regionalism and Nation merged in a dialectic relationship; tangible and intangible heritage abundantly contained in it took on a specific ethical value on the basis of considerations gathered from national culture.

De Giorgi, also in this text, is in line with those scholars who argued that civilization should be grounded on native land memories; his studies aim to reveal the relationship between monumentum and documentum, namely between place history and texts.

Especially in the second half of the nineteenth century, the study of sources, although philologically accurate, was mostly the prerogative of old generation intellectuals, whereas the new generation deemed the practice of visual analysis and first-hand confrontation with places essential. De Giorgi belonged to that quite small group of Apulian scholars who tried to combine the critical study of sources with direct observation of places, achieving significant results. Within this perspective, in a country that had been recently unified – although only formally – history became a fundamental discipline merging studies that were apparently very distant: in the same text the observation of rocks coexisted with a critical interpretation of myths and antique studies were accompanied by engineering and technical building analysis.

As stated above, in this epistolary autobiographical prose the description of natural and urban territories coexists with another guideline that can be defined as emotional, already evident in the incipit. In Bari the traveler follows the street that separates the two parts of the town: on one side of the street, the old area winding roads and on the other, the straight and square lines of the modern area, according to a geometrical structure that follows the Murat model. The wide square that divides the two areas and the other town elements (from the port at the end of the street to shops and elegant boulevards) have an emotive impact on the writer, recalling his university years in Pisa.

Hence, the author establishes an osmotic relationship with the town, revealing his own feelings and his singular mood before the urban landscape. This is not a long description, but it focuses on few aspects considering all details (as fresh September north wind, or the dried up trees aligned in the middle of the square, or the shade of leaves on the ground): in this way, he delineates clearly the town scenery that was progressively changing and developing both in Bari and in southern and northern Italian cities in those years.

De Giorgi is a cultured traveler, interested in new and fascinating aspects he can capture unexpectedly; he longs to know reality from a different perspective, immersing himself in behind-the-scenes everyday life, not passively but rather paying assiduous attention to people moving across those places, as the “signorine svelte e avvenenti che lanciavano sguardi assassini, mentre cinguettavano un dialetto indiavolato che sente del Saraceno”.

His curious nature leads him to accept to reach Taranto by train, in a four-hour journey across the Apulian hinterland, from one coast to the other, namely from the Adriatic to the Ionian Sea. The long letter is structured around compact blocks of impressions, which reflect the structure of Romantic narration. When he meets other passengers, he asks a series of questions aimed at getting various information: for example, he would like to ask about the economic trend in relation to carob and almond growing, but he also wants to examine the relationships between citizens and institutions, animating group conversations. However, he often directs his gaze out of the window and sees plains and Murgia gentle slopes where pasture lands can be made out as in those landscapes painted by Salvator Rosa.

An essential component of his descriptions is that of colors: “il tappeto rosso dei fiori”, the “chiome verdi cupe delle carrube”, “gli strati sottili e bianchi” of limestone, “gli steli mezzo ingialliti del gran turco”, “le case imbiancate” in Modugno. It is a color, “quel bianco che si vede sotto le ceppaje degli ulivi” – on which the writer needs an explanation – that leads his interlocutor to describe a cultivation technique that involves the use of tuff at the base of grapevine stumps to keep roots fresh, as it is still done in the South of Italy. Hence, De Giorgi aims to provide his friend from Pisa, the addressee of his letter, with information about habits and customs as well as established and more or less effective agricultural traditions. As Elvio Guagnini recalls, the landscape “più complessamente inteso, che comprende la presenza dell’uomo e della sua attività”[7] is one of the most evocative themes in travel literature research.

Modugno, Grumo, Bitetto, Acquaviva, and Palo del Colle, with their aligned houses, the church bell towers and the evergreen area that surrounds them proving “a lungo andare monotona per l’artista come pel viaggiatore” run along the railway. In his descriptions, the writer points out that each town has a singular history that should be studied to understand the trend of its development. The route he follows offers him a wonderful series of views of the most important centers between Bari and Taranto, seen in a dialectic relationship between urban contours and open natural spaces, as his gaze wanders over the “cerulea frangia dell’Adriatico che limita il paesaggio sul confine all’orizzonte”. This is a minor part of Puglia compared to the two poles of Bari and Taranto, but is not presented here as less important.

Urban and natural areas harmoniously alternate and become in turn the focus of the description, taking a leading role. However, the writer’s attention is often caught by his occasional travel companions who are well-portrayed: an embellished description is that of the blonde lady “dagli occhi neri come l’ebano” silently sitting in the wagon with a baby in her arms and “tutta chiusa nel suo piccolo mondo”; the author describes vividly the two contractors who got on the train in Bitetto and “favellavano tra loro in modo assai concitato” while eating, or the lively and quick priest “con un cappello ad orli piatti come fosse la celata di Don Chisciotte”. The representation of individuals is then replaced by the characterization of a group along Acquaviva roads, where the train stops off. The town is excited and full of joyful people and peddlers who speak a “dialetto indiavolato ed una cadenza in si bemolle”, as the author had already observed in the county town.

He also mentions the possibility of being attacked by brigands at the secluded and unsafe San Basilio station, a site surrounded with wood and far from the other towns. From September 1860, when Francis II left Naples and shortly after the fall of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the more or less spontaneous anarchistic peasant uprisings led to brigandage. This phenomenon will upset the first steps of the national State and will have revivals in the following decades, as De Giorgi here states.

In the journey to Taranto, travel companions talk about the dispatches on Napoleon III events in Sedan, but he seems to record their conversation absent-mindedly and be rather interested in the land geography and geomorphology, which changes when he gradually approaches the Ionian coast, opposite the one he had just left behind. The view of Taranto sea is anticipated by the sea breeze smell. At late night the author reaches the town, “vecchia patria di Archita”, made fascinating by the surrounding fertile hills in the north and he devotes the last and densest pages of the long letter to his friend from Pisa to the Magna Graecia center. Taranto is observed in its complex and contrasting relationship between the past and the future, or between not much legible old inscriptions scattered around the town and modern cafés, shops and workshops. The town description gives the author the opportunity to show his wide classical knowledge, recalling the leading role Taranto had during the reign of Augustus and quoting the authors born in Taranto or the writers that had praised it in their works, implicitly underlining the historical gap between the Graeco-Roman and the modern town. Taranto gives a hint of decline, although it is projected into the future[8], more than other Apulian cities; but this future swallows, adorns and conceals classical antiquity: “Le reliquie dei suoi vetusti monumenti sono tutte sepolte sotto le fondamenta di costruzioni più recenti”.

In line with many Italian and foreign travelers,[9] De Giorgi describes the Ponte girevole (swing bridge) opened in May 1887: it separates the Gulf of Taranto from the Mare piccolo and was built to meet the Navy’s needs and allow big ships to cross the channel between the Mare Piccolo and the Mare Grande; the author dwells on seafood breeding techniques and fishery, whose rules were still contained in the Orsini Libro rosso. In short, Taranto is a town where local traditions are preserved and, at the same time, new expressions of progress are experienced. The long letter last pages confirm the general trend of the text: the descriptive passages are connoted by both the image of the Magna Graecia town microcosm (the natural, cultural, and social world, etc.) and the role of the scholar, observer and narrator who portrays the “vecchia Regina dello Jonio” also through his ideas and impressions. At the end, he quotes Paisiello’s verses in saying goodbye to the town,“più bella, la più splendida, la più potente città della Magna Grecia”.

Nota al testo

L’edizione digitale che qui si presenta è stata fedelmente trascritta dall’edizione a stampa del 1872; è quindi riconducibile alla volontà di non alterare il colore epocale la conservazione di grafie oggi non correnti (diffatto per di fatto, diggià per di già, dapertutto per dappertutto) o di grafie oggi considerate scorrette come la i nei plurali dei nomi i cui nessi –cia e –gia sono preceduti da consonante (Murgia → Murgie, ganascia → ganascie, quercia → quercie, roccia→ roccie, malconcia → malconcie), come prevedeva la grafia tipica ottocentesca (Serianni 1988: 39).

Si è ritenuto invece di emendare alcuni evidenti refusi tipografici (costrazioni corretto in costruzioni, bizeffe corretto in bizzeffe, un’aspetto corretto in un aspetto, inebbriato corretto in inebriato).

-

The pamphlet here reproduced is available at the Biblioteca provinciale “Nicola Bernardini” in Lecce. It is one of the only two libraries in Italy (together with the Biblioteca “Caracciolo” in Lecce) to keep some copies of the text. ↑

-

C. De Giorgi, Da Napoli a Foggia. Impressioni di un viaggio nell’aprile del 1870, Wilmant, Milano, 1872. ↑

-

Id, La Provincia di Lecce. Bozzetti ed impressioni, Tipografia Campanella, Lecce, 1877. ↑

-

For example, the restauration of the portal of the “Santi Niccolò e Cataldo” church in Lecce and the discovery of the Roman amphitheater in the same town. ↑

-

C. De Giorgi, La Provincia di Lecce – Bozzetti di viaggio, Editore Giuseppe Spacciante, Lecce, 1882. ↑

-

See: M. Leone, Cosimo De Giorgi tra scienza e letteratura, in Atti del Convegno internazionale AATI, Lecce, 26-3 maggio 2010, a cura di P. Guida e G. Scianatico, PensaMultimedia, Lecce 2011, pp. 121-142. ↑

-

E. Guagnini, Viaggi d’inchiostro: note su viaggio e letteratura in Italia, Campanotto, Pasian di Prato, 2000, p. 9. ↑

-

See: G. Dotoli, Paesi che si danno la mano in Viaggiatori dell’Adriatico. Percorsi di viaggi e scrittura, a c. di V. Masiello, Palomar, Bari 2006. ↑

-

Bibliography is extremely extensive on this subject; since we cannot provide here a comprehensive overview, we may simply mention the texts consulted to write this introduction to De Giorgi’s work: M. Hermann, A. Semeraro, R. Semeraro, Viaggiatori in Puglia dalle origini alla fine dell’Ottocento, Schena Editore, Brindisi, 2000; L. Clerici, Alla scoperta del Bel Paese: i titoli delle testimonianze dei viaggiatori italiani in Italia (1750-1900), in «Annali d’Italianistica», n. 14 (1996); F. Silvestri, Fortuna dei viaggi in Puglia, ed. Capone, Cavallino 1981. ↑